| Wes Boyd's Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

| Wes Boyd's Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

"God, is she going to be in there all day again today?"

The Hollywood Tonight producer Jennifer thought of as "Weasel-face" actually had a name: Lenny.

The cameraman, who she thought of as "Greaser," tried to use a tough-guy image to overcome the name of Sherwin. "Yeah, is this going to be the most interesting footage since Snake River Canyon, or what?" he snorted.

Both Lenny and Sherwin were lounging on a bench in the shade of a small tree in the parking lot across from the Record-Herald. It was hot and humid; both were wearing T-shirts and shorts, but the heat and humidity was something they weren’t used to. Other than that, Spearfish Lake hadn’t been the Black Rock that they had expected, a relatively decent little town, for a little town, duller than dishwater. They’d wondered if they were going to be facing angry mobs armed with axes, but so far, this trip had been a total waste. They’d gotten a few background shots of the town, and of some kids swimming at the beach, but darn little of Jenny Easton. The only interesting footage they’d gotten had been a poor shot of her and some other woman helping some pregnant woman into the hospital yesterday, but it had been at a distance, at a bad angle, and probably wasn’t usable.

"Well, we can still get some interviews from the local yokels about how great it is to have Jenny home," Lenny said. He hadn’t been too crazy about the assignment; it sounded like a waste of time, but the orders were to stick around and get something. "Cut that in with some stock shots, a couple distance shots, and it’ll make a story. We get paid if we do something, and we get paid if we do nothing," he said.

"I still don’t think she knows we’re here," Sherwin commented.

Lenny agreed. "She hasn’t acted like it, anyway. If that big lug she keeps around had been here, I think he’d have spotted us, though."

"Well, we ain’t exactly been laying low," Sherwin said, looking up. "Oh, hey, shit, there she is."

Lenny had been checking out the boobs on a long-haired girl walking down the sidewalk. He swung his head around to see Jenny standing on the sidewalk in front of the Record-Herald, waiting for a break in the traffic. Out of the corner of his eye, he could see that Sherwin already had the camera on his shoulder, running. It took several seconds for the traffic to clear. "Best shot of her we’ve got so far," Sherwin commented, as she walked across the street, and got in her car.

Lenny was already heading toward their car. "Come on, man, we’ve got to move."

They had a tough time keeping her car in sight while getting out of the parking lot and, but once they got out on Main Street, it was no trick trailing her from a couple of blocks behind. As they got out to the edge of town, they could see her turn signal going for a right turn onto the state road. "Not trying to lose us at all," Sherwin said. "She still hasn’t caught on."

"She’s not going home again," Lenny said. "Six will get you two she spends the next four hours shooting the shit with some old friend, some place where it’s air conditioned."

"Maybe it’ll be someplace where somebody has a beach. We might get a bikini shot or something," Sherwin said.

"The way this has been going, that’s a bit much to hope for," Lenny said. "Christ, I didn’t expect the job to be this boring."

Three or four miles up the state road, they could see Jenny’s turn signal going again, this time for a left turn onto a gravel road. "So much for a bikini shot," Sherwin snorted. "The lake is the other way."

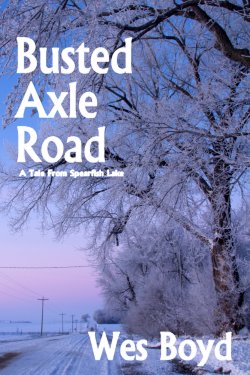

Lenny slowed for the corner. There was a sign there with an arrow, saying "SPEARFISH SIGNS," and another that said, "DEAD END." He turned onto the road, and immediately wished he hadn’t. "Don’t they ever grade these goddamn roads?" he said.

"You see the name of this road?" Sherwin said, gritting his teeth and looking at the dust cloud in the distance caused by Jenny’s passage."

"No."

"Busted Axle Road."

"Christ, I believe it." They weren’t going fast, but neither was Jenny. After a ways, they passed a house on their right, and pretty soon, Jenny turned into a farm on the left. "Let’s drive past, and turn around," Lenny suggested. "She’ll have to come back this way to leave."

A few minutes later, they came to a stop a couple of hundred yards past the farm, the one with the arrow to the sign shop in the yard. "Get a wide shot, just in case," Lenny suggested.

Sherwin was already getting out of the car, but he got right back in, in one big hurry, cranking the window hard as he did, just managing to stop three large dogs who snarled at them through the glass.

"Where the hell did they come from?" Lenny asked, cranking on his own window.

"Christ, I don’t know," Sherwin said, cringing as a large red dog barked at him through his window, his paws on the pane. "All of a sudden, they were right there."

"I think everybody in this neck of the country must keep a yard full of dogs," Lenny commented, disgusted. "I wonder if they use them to pull dogsleds in the winter."

Sherwin looked outside, to see another dog lifting his leg against the front tire. The red dog barking in his ear was distracting, to say the least. "Hey, there she is," he said.

"Where?"

"Out back of that barn. Oh, shit."

Lenny looked out the windshield; there was now a dog barking in his own ear, as well – a big black one. Back behind the barn, they could see Jenny putting a suitcase into the back of a small, white airplane. "She’s going somewhere," Lenny said.

"Maybe that cottage we heard about," Sherwin said, watching Jenny climb into the right seat of the plane.

"Can you get a shot?"

"With these damn dogs?" Sherwin snorted. He watched for a few seconds, and could see the propeller on the airplane start to turn. "How the hell do we follow her now?"

"Maybe the plane’s not real fast," Lenny said hopefully, watching the control surfaces flop. "If it follows a road, maybe we can keep them in sight if we drive like hell."

"You’re crazy."

"Sherwin, she’s got to know we’re here. If she’s trying to lose us, then where she’s going might be our story." He started the engine as the little white plane began to race down the runway. "It’s probably not far away, so it’s probably worth a shot. Try to keep them in sight."

The road had been bad enough to drive down slowly, but the way that Lenny stuffed his foot into the engine, it wasn’t actually quite so bad – as they were only hitting the high spots. Sherwin tried to remember a line he’d learned as a kid, but "Hail Mary, full of grace . . . " was as far as he could get. They got out to the corner of the state road, and Lenny jammed on the brakes. "Can you see them?" he asked.

"Over to the south, not far," Sherwin said. "Heading back towards town."

"All right," Lenny said, turning onto the state road with a screech of rubber, and stomping the gas.

Fortunately, there was little traffic, which was good, as the speedometer needle in the Dodge was bent way over to the right – but he could see that they were actually gaining just a little on the small white plane. This might work after all. "Christ, I hope the cops are all in the doughnut shop," Sherwin commented.

Lenny slowed a bit as they came into the outskirts of town, getting the needle back under a hundred, but they were flying as they went through the Main Street intersection and continued south, with Lenny’s foot on the floor.

With their attention riveted on the plane, it was more than a little too long before they noticed that they had company. "Oh, shit," Lenny commented. "All the cops aren’t in the goddamn doughnut shop."

There was nothing they could do but pull to the side of the road and stop. The cop car, lights flashing, slid to a stop behind them. Two large cops sprang out, guns drawn. "Out of the car, motherfuckers," one of them yelled.

"Let’s be cool," Lenny said, opening the door.

"He said out of there, motherfuckers," the other cop yelled.

"I can be cool," Sherwin replied, opening his own door. "You were driving."

Don Kutzley kept a scanner going in his office, not because he was any particular fan of the Spearfish Lake Police, but as city manager, he needed a way of keeping a finger on what the police department was up to. He heard the call, "Base, Six-Two out on a traffic stop," but that was common and another one didn’t have any real significance; he never gave it a second thought. His attention was more on the mail, anyway.

There was always a wad of mail, some days worse than others, and a fair amount of it came with his name on it, so he couldn’t leave it to the office girls to go through.

This Friday, though, the mail wasn’t too bad, but it had already brought bad news. The first letter he’d opened was from the Farm Home Administration, giving flat denial to the request for assistance with construction of the storm sewer separation; there wasn’t even a suggestion to reapply at a later date. That was fast work on the part of the FHA; he hadn’t expected a reply, good or bad, for at least another six months. Don had already made a note to bring it to council the next Tuesday night, and council wasn’t going to be very pleased.

It sure would be nice to finesse this one, somehow or other, he thought. A big project, successfully funded and completed, would look real good on the resumé, and it wasn’t too soon to be thinking about getting a few out.

Kutzley wasn’t a Spearfish Lake native; he was from Nebraska, in fact, and his last job had been as assistant city manager and city treasurer of Chatham, Florida. Once, he’d wanted to be a politician, run for office, but back when he couldn’t even get elected to student council in high school, he’d realized that being an elected official was a precarious way to make a living, at best. Still, he’d had a real interest in government, so had taken to public administration, instead. It had proved to be the right choice for him; it provided most of the joys of being a politician, but few of the pitfalls.

To Don, Spearfish Lake wasn’t a lot different from Chatham, from Muscatine. They were still all small towns, and they all took a bit of learning. There was a hidden power structure, no matter what the voters said; every town had a couple of loudmouthed old women who came to all the council meetings and bitched ignorantly about anything and everything that happened; any town like Spearfish Lake had their own agenda, one where government was rarely high on the list, except maybe when tax time rolled around, but most of the time it was easier to get a discussion going about football than it was to start one on property tax equalization.

Don could take football or leave it, but he preferred to leave it. Though he stood six foot three, and weighed over 300 pounds, he’d never played football in his life, at least not since throwing a ball around on an elementary school playground. It was, at best, rather primitive and brutal, and there were more important things to do that caused less bodily harm.

He brushed back a hair on his prematurely balding head and opened the next letter.

It was from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and it was short:

"Having received no public comment or request for public hearing, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service hereby declares an area within a radius of ten miles from the city of Spearfish Lake, including the city of Spearfish Lake, as an interim critical interest area for the species Nerodia sipedon gibsoni, Gibson’s water snake."

Sheer gibberish, as far as Kutzley was concerned. What did that have to do with anything?

He reached for the next letter. It was from the Environmental Protection Agency, and that was hardly ever good news.

It wasn’t. It was hardly longer than the letter from the Fish and Wildlife Service, but Kutzley understood what this one meant, every word. This would have to go to council, too, and council wouldn’t be pleased, one bit.

His attention was drawn by a knock on his open door, and a deep voice that could only be Jack Musgrave’s: "You in for me, chief?"

"Yeah, sure," Kutzley said in a grinding, high-pitched voice. "How’s things down at the plant?"

"Oh, pretty good," Musgrave replied. "We steam-cleaned the basement yesterday afternoon, and it’s not too bad in there, now."

Ninety-nine people out of a hundred in Spearfish Lake would have said that Jack Musgrave probably had the most disgusting job in town, running the waste water treatment plant. Actually, most of the time, it wasn’t bad at all. When the plant ran smoothly, which it usually did, it mostly consisted of puttering around. While most people had the impression that it was rather worse than working in a manure pile, it was usually clean and sparkling. There was a slight smell, but one you didn’t notice after a few minutes – except when the plant overflowed, like it usually did after a heavy rain. The overflow was always confined to the basement, and when the plant overflowed and filled the basement in the summer, it did tend to reek a bit until the basement was steam cleaned. Steam cleaning took a nasty couple of hours, but Musgrave never let it get out of hand.

"What’s on your mind today?" the city manager asked.

"Got some good news, for once," Musgrave reported. "We’re going to have the crew down here first of the week, to run the TV rat through the sewers. Going to get the whole system done, and have a few bucks left over in the budget."

"It seems to me council only gave you four grand for that, and it was going to cost twelve something. How’d you pull that off?"

"Got lucky," Jack reported. "There’s this girl from town, here, working on her doctorate, and her project has something to do with snakes living in sewer systems . . . "

The girl who’s been running around town for the last couple of months, sticking a periscope down the storm drains?"

"That’s her," Jack replied "She managed to finagle some foundation for ten grand for TV surveillance. When she was trying for it, back last spring, I agreed that I’d come up with a couple grand for local match, given that we’d share the videotapes. So, a couple of grand, plus a couple of hundred for blank videotapes, and we get a second original of the whole system."

"That’s a good deal, even for luck," Kutzley said. "Now, what is it you hope to find?"

"Well, she’s hoping to find snakes, obviously," the waste water treatment plant manager reported. "Me, I’m looking for breaks in the system, where storm water is getting into the pipes where it isn’t supposed to. The more of those we can isolate to surface runoff, the less we have to run through the plant. Maybe as much as ten percent of what we have to run through the plant after a heavy rain could be coming from breaks like that. That’s just a guess; I don’t know for sure."

"Yeah, but the system is supposed to carry off storm water," Kutzley said. "Otherwise, it just adds to the flooding problem."

"Some places, but not others," Musgrave replied. "I mean, if it’s in a place it’s supposed to be going down to the swamp, and it’s getting into the system, instead, we’re processing water we don’t have to."

Don shook his head; there was no point in bottling up the bad news. "It’s probably not going to matter a whole hell of a lot," he said. "It looks like we’re going to have to put in the separation project, like it or not."

"How’s that?"

"Let me read you this letter from the EPA," he said, picking it up off the desk. "‘Under section blah blah blah of the Clean Water Act of 1984, you are hereby informed that as of July 1, 1988, the city of Spearfish Lake will be fined ten thousand dollars per day that the discharge of the waste water treatment plant is out of compliance with state and federal regulations. As of July 1, 1990, the fine will become twenty thousand dollars per day."

"Ouch."

"Yeah, ouch. And, we just got turned down by Farm Home. I’m not looking forward to Tuesday night."

"Maybe we ought try and go back to the motel," Sherwin suggested, pulling in his thumb and turning around as the car flew past. He was bleeding from the elbow and knee, and his whole body ached. His skin felt like it was on fire.

"No way, baby," Lenny said. He’d lost his glasses somewhere back in the swamp, and was even worse off than Sherwin. He was past swatting at mosquitoes; it didn’t help anymore. "You heard what those two said. If they caught us again . . . "

"It was a thought."

"Fuck your thoughts, fuck that town, and fuck Jenny Easton. My job isn’t worth going back there, and there’s nothing in our luggage worth it, either." Lenny stumbled a little on some irregularity in the gravel alongside the state road, far to the south of where they’d been stopped a couple hours before. "We were lucky we got out of that swamp alive." He heard another vehicle approaching, and turned around to stick out his thumb. If they could get to the next town, then maybe they could rent a car. Thank god he still had his wallet.

The approaching vehicle was a dirty, battered old blue pickup truck, and it was slowing. Both Lenny and Sherwin’s heart skipped a beat; they might live, after all.

The truck stopped next to them. From inside, a man’s voice called, "Where you boys a headin’?"

"Trying to get to the next town, or to the Camden airport," Lenny replied.

"Waal, hop in, yaah," the man said. "I blowed me a transfer case, an’ I godda go down to dat Camden to get me anudder. Ain’t too far from the airport."

Lenny was first into the cab of the truck, with Sherwin hot on his tail. The driver was a tall, thin man in his thirties, with disheveled sandy hair, wearing a greasy, dirty T-shirt and greasy, ripped jeans. He had grease stains here and there, as well, and it looked like he’d just crawled from under some oily machinery. "God, we really appreciate this," Lenny said. "We’ll make it worth your while."

"Holywa, what da hell happened to ya two?" the driver said, pulling back out onto the highway.

"God, are all the cops around here like that?" Sherwin asked over the blaring country music on the radio.

"Like what, yaah?" the driver asked.

"We got stopped for speeding," Lenny explained, unable to come up with much of a better story in his condition.

"One of dem cops a big guy, and da udder one bigger, walks with a limp?"

"Yeah," Sherwin said. "Why the hell they aren’t in a zoo someplace is beyond me."

The driver of the pickup smiled. "Sounds like you run into Harold and LeRoy. What’d they do, take you about six-eight miles up da two-rut south of the lake, dump ya out, and let the bugs see if they can eat ya before you can find your way out? You musta been speedin’ pretty good. Usually, dey only do that to drunks."

"I’d have sworn it was twenty miles," Lenny said.

"Naw, if’n it’d been twenty miles you wouldn’ta been gettin’ outta dere," the driver said, smiling. "Dey only do that to people dat dey don’t like. Some deer hunters found a coupla skeletons back out dat far one time. Dey said they musta been lost, but everybody knowed that Harold and LeRoy musta really been pissed."

"They acted pretty pissed as it was," Sherwin said.

"Deyre’s pissed, and deyre’s really pissed," the driver said. "I ’spect if’n they saw you again, dey’d be really pissed."

"How the hell can you live with cops like that?"

"You don’t let ’em catch ya drivin’ drunk," the driver smiled. "Ain’t been too many people tried it a second time. Keeps things nice and quiet. You boys from around here?"

"Los Angeles," Lenny admitted. "We intend to get back there as quick as we can and not ever leave town again."

"Now, Los Angeles, I don’t know how I’d fancy that," the driver smiled. "All da traffic, all the niggers. Best to have Harold and LeRoy a-keepin’ things quiet. By da way, da name’s Slim. What you boys doin’ here, anyway?"

"We were trying to get some film of Jenny Easton," Sherwin said, without thinking.

"Know who you mean," Slim smiled. "Dat ain’t her real name. You musta not told Harold and LeRoy dat."

"Why do you say that?"

"Waal, dis was ’fore my time," the driver said, spitting out the open window of the truck. "But you know dat real big cop? Da one that walks with a little limp? Well, he and her daddy usta play football together, back in da fifties, and one day dey got into a fight real bad, over some girl, I guess. Well, anyway, her daddy kicked the livin’ shit out of Harold. The only man ever done dat. Made ’em the best of friends. If he’da knowed what you was here for, they’da drug you so far out in the swamp the skeeters woulda sucked you dry by nightfall. Some say them two skeletons was some film crew, lookin’ for Jenny, but me, I tink maybe dey was just drug dealers."

"Much of that around here?" Lenny asked, trying to change the subject a little.

Slim shook his head. "Wouldn’t expect there would be, if Harold and LeRoy found out about it. Dey’s lotsa folks’d call them up in a minute if they heard about somethin’ like dat."

"What do people do for a living around here?" Lenny asked, still trying to get away from the increasingly depressing subject of the two cops.

"Oh, cut pulp, like me, work in da mill, draw welfare, like dat," Slim explained. "Ain’t a lot of money here, but it’s home."

"How do you work out in the woods with all the mosquitoes?" Sherwin asked. "My god, I thought they were going to kill us."

"Oh, you grow up here, you don’t notice ’em too much, unless dey real bad. You go back in da woods in da day, dey ain’t real bad. You boys is just lucky dey didn’t drop you out there at nightfall. Dey do get a little bad sometimes, then."

"There were clouds of them," Sherwin said, unable to let the experience go. "God, I could hardly see. They were even trying to bite my eyes. We were running as hard as we could go, and they were still all over us."

"Well, you don’t go out in the woods, even durin’ da day, without you wear a wool shirt and pants," Slim explained. "It does get a mite uncomfortable on a day like today, so I was kind of glad I had me some work to do on the loader. When it gets to be da blackfly season, some people don’t even go to work, but we’re through the worst of the flies, now. Damn blackfly bite is worse than a mosquito bite; holywa, dey even bodder me some."

"It wasn’t that bad in town," Lenny commented.

"They spray in town," Slim explained. "Keeps ’em down pretty good. You know you ain’t supposed to spray dat DDT no more? Some goddamn environmentalist sold those bastards in Congress on that, but don’t make no matter, cause there’s dis old boy, works for the city, knows how to make his own. Kinda sorry they do. If they didn’t spray, den we wouldn’t have all these goddamn summer people."

"Does it get cold here in the winter?" Sherwin asked.

"Yeah, a little," Slim drawled. "Maybe forty-fifty below, but it’s a dry cold, ya don’t notice it much, ’cept on the days it gets real cold. Harold and LeRoy catch someone drivin’ drunk then, they best have a lot of antifreeze in them, ’cause ya can get real cold walkin’ back to town widout a coat."

"I don’t intend to find out," Lenny said. "There isn’t enough money in Hollywood for me to go back there again."

"Me either," Sherwin agreed.

It was a long drive down to the airport at Camden, and Lenny and Sherwin were very glad indeed that Slim had taken pity on them. At the airport, they took him inside the terminal, and while Lenny and Sherwin poured beer down to cool off and rehydrate, Slim agreed to let them buy him a Coke. Fortunately, a plane was leaving in only a few minutes for Chicago, and they were able to get tickets. Slim went with them to the departure lounge. "Slim, I’m damn glad we met you," Lenny said, reaching for his wallet. "Here’s something for your trouble." He handed Slim a couple of hundred-dollar bills.

"Aw, shucks," Slim said, "t’wern’t nothin’. You keep that."

"Keep it, hell," Lenny said, "you saved our lives. It’s the least we can do."

"Well, all right," Slim said. "I guess I can."

Lenny and Sherwin were happy to collapse into the seat of the jet. "Thank God, back to the real world," Lenny said.

"Glad he came along," Sherwin agreed. "God, I wonder how people can live like that."

"I don’t know about you," Lenny said, "but I don’t intend to find out."

Back in the airport parking lot, "Slim" stood leaning on the pickup truck, watching the plane taxi out to the runway, a big grin on his face. As the plane started to take off, he looked at his watch, and figured that if he hurried, he could get the pickup back to the guy he’d borrowed it from, get cleaned up, and still make it back in time to see Kirsten and Susan before visiting hours were over with. Even so, there were a couple of loose ends to clean up. "God," he thought to himself, "Jennifer thinks she can act . . . "