Scuttlebutt moves fast around a newspaper. Fully aware of the fact that her husband was going to blow a circuit breaker if he had to put up with the kids all the time, Carrie heard that the Spearfish Lake Appliance store could be had for the right price. She and Gil thought about it for a while, and before long, Gil was in the business of selling televisions, dishwashers and stoves, and the kids were being left with a sitter.

The next months passed quickly and peacefully for Gil and Carrie. Both had been away from Spearfish Lake for many years, and it meant developing a new group of friends and a new style of living, but soon, it was as if they never had left, and the Army was far away.

One of the places Gil used to reestablish his roots in Spearfish Lake was the breakfast table at Rick’s Café, a block or so up the street from Spearfish Lake Appliance.

The big table, covered with oil cloth, was in the back of the room. It could seat sixteen, and, from about six-thirty until ten on weekday mornings, all seats were usually filled, and the waitresses could set their watches by the changing of the occupants of the chairs.

The character of the table changed as the morning went on, however. Early on, it was loggers and factory workers, but by seven-thirty, it was teachers and factory managers. Starting from around eight, retailers began to filter in; but those left by nine-thirty were retirees. Yet, the table was highly democratic; who got there first, not social status, ruled who got seats at the table, and a factory worker could sit elbow-to-elbow with the factory owner or bank president, discussing politics, movies, women, or the latest Marlin game.

Since the breakfast table at Rick’s was an all-male affair, the conversation ran heavily to sports. Pro sports, however, were rarely a topic, due to the location, which fairly evenly divided fans of several large cities; the state college was such a nonentity that no one ever entertained any positive feelings.

High school sports, though, were a different story. Every bit of gossip about the Spearfish Lake Marlins was tossed around the table until it was beaten to death, and this morning, the debate was how much the Szczerowski kid rendering his girl friend pregnant was going to affect his quarterbacking once the season got under way. It had been a long time since Gil had been a major sports star for the Spearfish Lake Marlins, but there were those who remembered, and a number of people who had been on teams with him had breakfast at Rick’s, too.

The one exception to the rule that high school sports were a main topic came in November, with deer season. Gil had enjoyed deer hunting as a kid, but in the first November that rolled around after he got out of the Army, he discovered he just didn’t have any interest in it any more. He’d spent enough time in the woods shooting at things to suit him, and didn’t care for venison. No one faulted him – after all, no one was about to find much fault with a former Marlin football star who was a retired Green Beret sergeant major with CIBs from Korea and Vietnam. It did make the conversation for him a bit bleak during that part of the year, but Gil just sat back, let others tell their tales of derring-do, and kept his own to himself.

Often business got dealt with at the breakfast table, and sometimes other matters, too. One gray, blowy, snow-threatening day late in deer season, Gil was relieved to see Bud Ellsberg come in and sit down across from him. He waited to talk to Bud a little confidentially, and as luck would have it, Ryan Clark also came in and sat down next to him – another person Evachevski wanted to talk to. Gil signaled to Harold Hekkinan to join the rump discussion.

“Carrie told me last night that Steve Augsberg is back,” he told the group in a low voice.

“How’s he taking it?” Hekkinan asked.

“Not real good,” Evachevski said.

Clark nodded, and added, “Not good. I had the scanner on last night, and I heard the cops picked him up. D and D. Took him home, though, not to jail.”

Hekkinan shrugged. “I’d hoped to wait till the weekend, but I guess we’d better do it tonight. I’ll get hold of the guys.”

The Spearfish Lake Bar and Grill was almost empty. It was late in the afternoon, and it wouldn’t get busy until the shift changed at Clark Plywood, but Steve Augsberg had decided to get an early start.

There wasn’t much else to do, anyway.

He was already on his second beer, but he wanted to get puking drunk again. He had looked forward to getting out of the Army and coming home for two years, and when he finally made it, it wasn’t worth the effort. His old girl friend had gotten married, to some son of a bitch 4-F who had never had to even worry about the draft. He’d known about it for a year or more, but knowing it and seeing her with a baby in her arms that wasn’t his didn’t make it hurt any less.

He would’ve liked to have gone out and partied with his old friends, to be welcomed home after being gone so long, but most of his friends were gone, or they had families, and they didn’t understand or didn’t care to.

He hadn’t even thought about getting a job yet, or about what he was going to do, but he’d already learned jobs were hard to find that year.

It was not the homecoming he had looked forward to, and that made it hurt all the worse.

He heard the door open, and someone came in, but he didn’t look up; he just signaled the old girl behind the bar to bring him another one. In a minute, she brought him a draft, and he reached in his pocket to pay her.

“I’ve got it,” a voice next to him said, waving the bartender off.

He looked up, to see Coach Hekkinan, his old football coach. He looked around; there were half a dozen or more others surrounding him as he sat on the bar stool. While he recognized the faces of a few, the only faces he could put names with were Coach Hekkinan’s, and Mr. Ellsberg’s, and Mark Gravengood’s. He had played football, and had been a bag boy at the Super Market; Gravengood had been two or three years ahead of him in school, and had been rabbit hunting with him and Jody and Henry Toivo a few times.

“What do you want?” he asked, a little sullen and a little scared.

“Want to buy you a beer, kid,” Coach Hekkinan said. “Doesn’t look like anyone else wants to, but we do.”

“You come and sit with us,” Evachevski said, in a tone that was just short of being a direct order.

“I’m not in the mood for any lectures about being a good little boy,” Steve replied.

“So, you’re not going to get one,” Ellsberg said.

Just a little confused, Steve got up and sat down at the big table with the group. Evachevski nodded, and the old gal behind the bar brought a couple of pitchers over to the table.

Mr. Ellsberg sat down next to him, and poured him a glass. “Coming home wasn’t as great as you thought it would be?” he asked.

“I guess not,” Steve said in a whisper. “But you wouldn’t understand that.”

“You know everybody here?” Coach Hekkinan asked.

“Some of you,” Steve replied, still sullen.

“Then you don’t know that we’re all people who would understand,” Ellsberg said, sticking out his hand. “221st Aviation Battalion, mostly 1962. Welcome home, Steve.”

Steve shook his hand. Across the corner of the table, Evachevski reached out his huge paw. “Gil Evachevski, 5th Special Forces Group, ’63 and ’64. Welcome home, Steve.”

“Seventh Cavalry, 1965,” Coach Hekkinan said. That was a surprise; Steve had never suspected that he had even been in the service. “Welcome home, Steve.”

One by one, he shook their hands; by the end, his jaw was hanging open with surprise.

“Ryan Clark, Big Red One, 1966. Welcome home, Steve.”

“Glenn Mackey, Sixth Marines, ’67 and ’68. Welcome home, Steve.”

“Joe Krebsbach, Tropic Lightning, 1969. Welcome home, Steve.”

“Mark Gravengood, 82nd Airborne, 1967 and ’68. Welcome home, Steve.”

“Ed Snyder, Blackhorse Cav, ’66. Welcome home, Steve.”

“Bud said you ain’t gonna get a lecture,” Evachevski said. “But, I guess we want to give you an invitation. It’s real simple. None of us here are what you would call REMFs. There’s not a lot of us in this town who can say that, but we’ve all spent our share of time out beyond the green line. We have to stick together, and help out each other when we can.”

Clark spoke up. “Get rested up, get your head together, and when you get ready for a job, come on out to the plywood mill and see me.”

“I talked to the prosecutor this morning,” Bud said. “He says if you maintain your cool, he’ll drop the charge from last night.”

Steve shook his head. “Why are you guys doing this?” he said finally.

Gil looked hard at him, then topped off his beer glass. “We’re doing it because no one else will do it, and somebody ought to,” he said. “We’ve all been handed a bunch of shit about doing what we had to do, and someday those people will have to eat that shit back. Until then, there’s nobody else but us – and that includes you – so we’ve got to stick together. Tonight, we’re going to sit here, and get drunk with you, and you can get all the shit you’ve taken off your chest to maybe the only people in town who will know what you’re talking about, and for sure the only people who will care about it.”

Gil was not joking. Everybody else around the table knew it well, and Steve was learning it. By the mid-seventies there was not a lot of public honor about being a Vietnam veteran – in fact, there was a lot of derision about it, and many veterans didn’t even want their service there, or service at all, to be public knowledge. They could look at the veterans of other wars and view the honor in which they were treated, and many were bitter that at least some of the honor wasn’t extended to them. In many places, even traditional veterans organizations weren’t as friendly to the Vietnam veterans as they might have been, although there was more going on there than just the antiwar sentiment, involving local politics and a generation gap among the veterans.

Gil knew better than the rest what a screwed up mess Vietnam had become, and actually sympathized with the kids who had tried to avoid it. After all, he made no bones about the fact that he’d left the Army rather than being sent there again, though he’d have gone if he’d gotten orders.

Harold Hekkinan, the Marlin football coach, started the Spearfish Lake tradition of welcoming the fellow Vietnam veterans home. He’d been with the First Cavalry Division as a second lieutenant when the horse had first gone in-country, and he’d spent his fair share of time in the field as a platoon leader, had taken an AK round in the leg, and still drew a twenty percent disability. He’d been a few years behind Gil in high school along with Ellsberg, and he’d gone through college on a combination of football scholarship and ROTC, accounting for his time in service. He’d been teaching and coaching football down in Crestone when the Spearfish Lake school board canned the last football coach for ineptitude. Wanting to move back to his old home, he applied for the job and got it.

Joe Krebsbach’s younger brother had been on the football team the first year he coached at Spearfish Lake, and the coach had overheard the kid talking about his brother returning home and being spit on for wearing his uniform in public. That was a piece of shit, and Coach Hekkinan knew it. Gathering together Ellsberg, Snyder, Clark, and a couple of other vets he knew about, they’d found Joe drinking at the Spearfish Lake Bar and Grill, just like Steve. Just like this evening, they’d gathered around this very table, ordered pitchers, and did their best to make the point that not everybody hated him for doing his duty, and he’d better know he had some friends he could call on if in need. The guys who had done their duty were going to have to take care of each other, since no one else would.

The tradition had continued. Since Gil had been a twenty-year lifer and had been around the block before, his welcome home was more of a good natured beer bust and steak fry in Ellsberg’s back yard, but that usually wasn’t the case.

Soon the air was filled with words like “gooks” and “slicks” and “hooches” and “charlies,” and Steve knew the language. He’d been nailed in the July ’70 draft lottery and spent the last half of ’71 and part of early ’72 in-country before his unit had been pulled out, one of the last maneuver battalions to leave. He hadn’t seen a whole lot of action, but soon learned that most of the others had seen their share and more.

As the evening went on and the pitchers kept coming, Gil loosened up enough to tell for the first time of the chopper crash back in ’64, a story he’d never even told Carrie. Ellsberg could top it: as a door gunner he’d ridden a banana and a Huey down on separate occasions and walked away from both – something Steve had never known when he’d been bagging groceries at the Super Market.

Eventually, and inevitably, the conversation turned to Henry Toivo, who they all knew would have been sitting at the table with them if his luck hadn’t run out more than two years before. “Anybody ever hear what happened to him?” Steve asked.

“Afraid not,” Hekkinan said, shaking his head. “Gil knows more about it than anyone else.”

Gil briefly told the group about the call from Matson, and his request to his old Special Forces buddies in country. “Henry’s company and another one were on a sweep outside a fire base, up north of Phuoc Lot,” he reported. “It’s an area that apparently is a lot flatter and more open than the hills I was in about twenty or thirty miles away. From what Dennis and Bob learned, Henry and a Speedy-Four by the name of Taylor were way out on the flank. Taylor saw Henry go into a little patch of woods, but they were a little behind the platoon and he didn’t think much of it, and Taylor was hurrying to catch up, and didn’t look back. When Taylor finally caught up with the platoon, no Henry.”

“Didn’t they ever hear of keeping an eye on each other?” Krebsbach asked. “That’s piss poor.”

Gil shrugged. “Apparently Taylor was no great shakes in the smarts department, and frankly, the unit was a sack of shit. What Dennis said was, and I quote, ‘Poorly disciplined, little field skills, don’t give a shit attitude.’”

“Jesus,” Steve said. “And I thought I had some dumb shits in our outfit.”

“Yeah,” Clark said, “I guess things have gone to hell all around.”

“Anyway,” Gil said, getting back to the story, “Taylor told the squad leader, and the squad leader apparently didn’t think too much of it and the platoon leader had his head up his ass about something, so it was a while before he found out. The platoon leader was some dumb shit of a shavetail named Loveland, and apparently it was like three or four hours before he got it through his skull that he had a man missing, but by then they were well away from the area and it was getting dark. They wanted to get back to the fire base so they wouldn’t have to laager up some place, so I guess the company commander and the battalion commander didn’t hear about it till that night.”

“That Loveland must have been some piece of work,” Mackey commented. “I’m surprised someone didn’t roll a grenade into his hooch.”

“Someone did,” Gil said dryly. “It was a little after that, so I don’t think it was over Henry, but mostly because he was your basic asshole second lieutenant. Of course, nobody knew nothing. But, anyway, apparently the battalion commander, some leg named Wright, had his head screwed on halfway straight, and sent a sweep back through the area the next day, and no sign of Henry. They got pulled out of the area the next day, so didn’t look again, and after he didn’t turn up at the fire base after a few days, they reported him MIA.”

“What a cluster fuck,” Snyder said, shaking his head.

“Yeah,” Hekkinan agreed. “It’s not like the Cav, at least in ’64. There’s a half a dozen things that would have gotten people strung up by the nuts back then. Your greenie beanie friends looked again, right?”

“Yeah, about three weeks after it happened, after Garth called me and I got in touch with Dennis and Bob. They went through there two or three times with pretty good patrols over the next few months, and spent some time looking between the place where Henry disappeared and the fire base, and never found a trace, Dennis told me last year when he showed up in Germany. Not surprising, I guess. Anyway, Dennis said there was a real slight chance that Henry might have gotten picked up by an NVA unit they knew was in the vicinity but they never could get much good intel on. So, there’s just the slightest chance he could still be alive, in some bamboo cage somewhere.”

“A shit of a thing to happen to a nice guy like Henry,” Gravengood said. “I didn’t know him real well, but I used to go hunting with him and Jody, and you, Steve.”

“If he got separated from his outfit, why didn’t he just walk back to the fire base?” Steve asked.

“God knows,” Gil said. “Maybe he tried. Dennis said the woods there were lousy with booby traps, punji stakes and mines, and they didn’t go through them as good as they might have, which I can understand. You want my guess, Henry found one of them.”

“That’s such a piece of shit,” Steve said. “I mean I grew up with Henry, pretty much. I lived right up the road, and shit, we spent a lot of our time together. It sorta makes me feel guilty that I made it back and he didn’t. I mean, Jesus, what a fucking waste.”

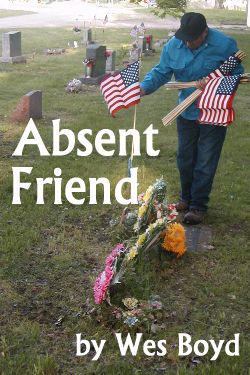

“We all have friends we can say that about,” Hekkinan said, shaking his head. “The only bright spot I can think of is that Henry is the only one from Spearfish Lake who didn’t make it back.” He picked up his beer stein and held it out in front of him. “Absent friends,” he said.

“Absent friends,” the rest of them chorused.

Several hours later, Carrie Evachevski and Kate Ellsberg finished driving the last of the drunks home. Gil was snoring peacefully on the couch when Carrie got a call from Kate.

“I hope we don’t have to do that again,” Kate said.

“With any kind of luck, we won’t have to,” Carrie replied.

“I hope so,” Kate agreed, thinking back several years. “I’ve been doing this too long, but I think that’s the last one.”

The Toivo family, Kirsten, and the little cluster of veterans refused to give up all hope until after the prisoners were released from North Vietnam in early 1973. In April, they held a memorial service for the young man.

In an act that earned lifelong disgust from everyone involved, the local Veteran’s Post refused to send an honors squad to fire a memorial salute – there was some sort of convention that weekend which was more important.

The group of Vietnam vets who had gathered in the Spearfish Lake Bar and Grill that November evening a few months before dug out old uniforms, some which didn’t fit very well any more. They didn’t have nicely matched M-1s like the Post; Steve Augsburg had the AK-47 he’d brought home as a war souvenir; Mark Gravengood borrowed his dad’s old ’03 Springfield. Gil borrowed an Enfield hunting conversion from his father in law; others had various hunting rifles, but they served to fire a final salute to the guy they’d really rather have been having a beer with. It drove home to each of them that they’d have to take care of each other, since no one else would.

Many in the county attended the service, and Heikki Toivo publicly thanked Garth Matson, Gil Evachevski and Gil’s friends for their efforts to find Henry, futile though they had been. And there, at a headstone above an empty grave in the Amboy Township Cemetery, the matter seemed to rest.