| Wes Boyd's Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

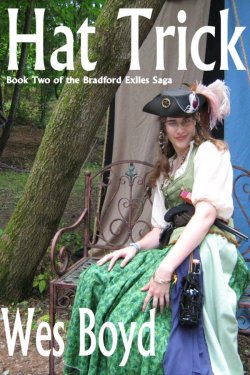

Hat Trick

Book 2 of the Bradford Exiles series

Wes Boyd

©2004, ©2010

Chapter 18

It was fun to just sit back and talk with some of the old gang while people kept plying Vicky with various drinks. The class of í88 wasnít large, and most of them had scattered. There were still two or three hanging around town who werenít at this party, but they were kids this group hadnít had much to do with. And, for that matter, everybody here but Emily had been going to school someplace, too, so most probably wouldnít be back once they graduated. People theyíd been close to might never be seen again.

And things had changed. John Engler, who Dayna had been in a back seat with once, and she remembered Vicky saying she had too, had now reportedly settled down with their old friend Mandy Paxton, another class of í88 girl, but one who hadnít had much to do with him in school. It wasnít a done deal yet, but looked serious. Theyíd apparently gotten together more because of being two kids from the same town at Eastern Michigan University, so they had that in common. Scott Tyler and Shelly Waltz both went to Michigan State, but they hadnít gotten together; in fact, they reported that the school was so big theyíd only seen each other to talk three times all year, and that just in passing. Scott had a girl friend up there, named Sonja, from Detroit, and to hear him talk about it, it sounded pretty serious. It wasnít mentioned at the table, but Emily had told Dayna the night before that Shelly had said that Sonja was pretty dark, so that was a real surprise for the class dreamboat. Shelly was making noises about dental school, so was trying to keep from getting hooked up with anyone.

"A lot of people we know arenít here," Dayna said as she watched John give Vicky a straight shot of bourbon with a beer chaser. "Some of them people Iíd love to know about. I mean, when I was in school I had lunch with Jennlynn lots of times, but I havenít heard a peep out of her in almost two years."

"Thatís, uh, a touchy subject," Emily admitted. "She spent the last two years out at Caltech like she planned. Well, one day, right back at the first of May, she came knocking on my door, carrying a couple suitcases and crying her eyes out. She said she needed a ride up to the airport in Hawthorne, so I loaded Kayla in her car seat and took Jennlynn up there. On the way I more or less got the message that her folks had thrown her out. Iím still not clear about why, and no one is talking."

"Whyíd she want to go to the airport up there?" Shelly asked. "There arenít any flights out of there."

"She had her own plane," Emily reported, "a little green and white one. She said she bought it to get her pilotís licenses; it wasnít real expensive. I didnít get much more than that out of her, she was crying so much. I got her up to the airport and tried to calm her down, but she was still crying when she got in the plane, started it up, and flew away. No oneís heard from her since, and her folks freeze up and get nasty when anyone mentions her name."

"Jeez," Scott shook his head. "Whatever it was, it must have been something bad."

"Probably," Emily nodded. "We might find out, and we might not."

"What about Pat McDonald?" Scott asked.

"Joined the Marines," Emily reported. "I guess heís out in the Gulf, but I donít know for sure. I try to keep up on everybody, since Iím about the only one thatís living here more or less permanently. I figure I can be someone to touch base with."

"It sure will be interesting to see whatís happened to everybody at our tenth class reunion," Scott nodded. "I guess if anyoneís going to organize it, youíll have to be the one."

"I guess," Dayna nodded, and spoke up a little. "Hey folks, letís ease up on Vicky just a little bit and drink some ourselves. Sheís getting ahead of us."

"Why donít you play something?" Vicky suggested. "I donít know if anyone here but me knows how much your music has changed from what you used to do back at the mall."

"All right, sounds reasonable," Dayna said, suddenly finding herself not in the mood to catch up on people sheíd most likely never see again. "If somebodyíll pour me another beer, Iíll get my guitar."

* * *

"Good God, my head hurts," Dayna moaned from the right front seat of Home the next morning.

"What did you expect?" Sandy chided as she drove north up I-67. "After all, you were the one who said you might as well get as drunk as Vicky. I was the good girl. I was the designated driver and was the one drinking nonalcoholic beer all evening. Which tastes like shit, I might add. I mean, if you canít get a buzz on, whatís the point?"

"It was in a good cause," Dayna said. "Tell me, Iím not remembering clearly. Did I do any Lucille Bogan?"

"No, and not even Eskimo Nell, either, but a couple times I thought you were getting worked up to do it."

"Pretty good party, though," Dayna grinned, in spite of herself. "I guess last night underlined that Iím the black sheep of the class, unless whatever Jennlynn did was really bad."

"Whoís this Jennlynn?"

"Oh, she was our class valedictorian, real smart, but real straight. Her folks are even straighter; her dadís a minister and real stuck up. She went to Caltech on a scholarship; she wants to design computer parts or something. Doesnít matter, I guess. Weíll probably never know. Anyway, fucked up head or no, itís good to be back out on the road, even if weíre pointed toward Unpleasant Flats."

"Yeah, but we get to drive right by it without slowing down," Sandy pointed out. "God, I hope we have a good summer up there. Thatís the key to a lot of things."

The weather the last few days wouldnít have made it worth going to Mackinaw City, but the weather was passing, so they figured that they might as well get on up there. They had one problem, probably not unsolvable Ė the little place theyíd stayed at out in the forest all the previous summer was about five miles out of town. If they couldnít find some place to park Home closer in, it was going to be a pain in the butt to have to tear down every morning and set up again every evening, sometimes way late. It was still a little early for the peak tourist season, but they figured they might as well get in what they could, since they had two weekends they could work the heavier weekend crowds before theyíd have to be spending their weekends at Maple Leaf. Even this time of the year, weekend traffic could mean thousand-dollar days, and a few extra of those in the bank account would make things a lot more flexible once summer was over with.

It was good to drop off of I-75 at the last exit before the Mackinac Bridge and drive up Central Avenue again. It wasnít a particularly nice day, but there was a fair amount of traffic on the sidewalks, so things looked promising. As luck had it, there was a parking space open right across from the totem pole, so they parked and went in to say hi to Cheryl, who solved their problem in one phone call. She knew of an elderly widow less than two blocks away who was trying to make ends meet on Social Security. It proved that the woman, Roberta Deborin, was more than willing to let them park Home in her driveway for forty bucks a week; they could even run a hose to an outside spigot, and an electric line to an outlet on her porch. She would even let them use her shower! Best of all, it was only two blocks to Sheplerís Ferry dock, and a block to the Keyhole. Theyíd have to move a couple times in the next couple weeks to go dump the holding tank, but that was it.

Dayna was over her hangover enough by now that they went out to work the sidewalk by the totem pole for a couple hours, just to get their feet wet, and after a while, wandered down to the Keyhole, had a little hair of the dog, and played for several hours; in the end, it wasnít a bad hat for only part of a day. The next morning, they were down at the ferry docks for the first time since the previous summer, and Bill came out to say a few friendly words to them as the crowds were starting to show up, so the core of their season was off and running.

Early the next afternoon, theyíd just set up by the totem pole and were trying to gather their first real crowd of the day in that location. This, theyíd learned, was not something for light and delicate; something with a little power was called for. Cold Cold Heart was one of their favorites, but this time, for no particular reason, they started out with a fairly heavy version of House of the Rising Sun Ė the old version, not the Animalsí version. Dayna was in a good mood and was especially in to it, but traffic was light and they werenít drawing much of a crowd. But they did get applause, from Cheryl and a man with her at the door of the business.

"Missy, you beat the hell out of that thing," he grinned. The girls looked at him; he was tall, slender, in his forties at a guess, with thin, graying hair and a salt-and-pepper beard Ė and possibly the most disreputable-looking cowboy hat east of the Mississippi.

"Thanks," she grinned. "We try."

"Sandy, Dayna," Cheryl grinned. "Iíd like you to meet a special friend of mine, Steam Train John. Heís in town to do a show for us this weekend."

"A show for you?" Dayna asked.

"Yes," Cheryl said. "We have dogsled races here in the winter, and John comes up to play for the Musherís Banquet. Thatís built a group of fans, so we decided to do a show in the spring."

"Miss," he said to Dayna, "Can I borrow your guitar for a minute?"

"Yeah, sure," Dayna grinned, expecting something special.

It was Ė John picked at it a couple times, then launched off into a folk song that had a lot of energy, about a guy who jumped ship to find a gold mine back in the Alaskan gold rush days.

Dayna and Sandy looked at each other. This guy could play a guitar! He ran through the song, which was fun with a lot of energy, then handed the guitar back to Dayna, who asked, "Did you write that?"

"Among others," John grinned. "Iíve written a few. Canít even tell you how many. Not even sure I remember íem all, anyway. Cheryl tells me you kids are working as street musicians."

"Well, yeah, but we do some renaissance faires and play some other gigs every now and then."

"Know how that works," he smiled. "I worked the streets for years. One time, I was still living with my girlfriend before we got married, we were up in my cabin in the woods on the Kenai, and we were out of money and just about out of food, and she was getting a little uptight. I told her, ĎDonít worry honey; Iíll just go play my guitar.í She was about ready to leave me, but we went into town, I sat down in a bar, put my hat out and started playing. Hell, I knew I could do it; I did it for years, and kind of miss it in a way."

"Youíre not a street musician anymore?" Dayna asked. "What do you do?"

"When the kids got to a point where they had to be in a regular school, I decided I better get a real job, so Iím now a songwriter down in Nashville. I still play a few bars and other dates to keep my hand in, and have some CDs out."

"Way cool," Dayna said. "Boy, would we ever love to pick your brain."

"Mightís well, if I can play some with you," John grinned. "I wasnít doing anything else this afternoon but trying to get in Cherylís pretty hair. Let me run and get my guitar out of my car."

* * *

It was a most interesting afternoon. The girls would play something, then John would. He was as good at hat lines as Tim, and had some interesting twists to them, although the money went into their hats. Their tastes werenít close Ė the girls, as always, were more into blues and pop and renaissance faire ballads, while John went toward country-western and modern folk ballads, but he knew some blues and lots of other music Ė a huge range of stuff. At the end of the afternoon they were sure they had barely scratched the surface. They played a lot of their original pieces for him, and some of their favorite workovers of old songs, and he was glad to critique them, giving good constructive help. The hats were mostly moderate, since they spent a lot of time between songs talking about them.

What was most important was that he had a different, and more modern, view of the business than Tim, their primary mentor up to this point. As daylight dwindled, they headed up to the Keyhole, not to play, but to talk and learn. And learn they did.

"I canít believe you donít have some CDs for sale," he said at one point. "Hell, thatís a gold mine."

"It would be nice," Dayna replied, "but I donít know the first thing about how weíd go about getting in with a record company, unless maybe you could put in a good word with us."

"I could do that," he said. "But my contacts are all in country-western, and you donít do that. But, thatís not the point. CDs sell for twelve or fifteen bucks each, right? Do you know what it actually costs to make a CD? I mean press one out?"

"No idea," Sandy shrugged. "Several bucks each, anyway."

"Wrong," John smiled. "I can think of several places that you can get a thousand CDs made, in jewel cases with color-printed cards, at about seventy-five cents apiece. Now, if youíre in with a record company and you have a CD being sold on the regular market, the merchant gets about forty percent of that fifteen bucks, less if heís discounting it, which is why thereís a lot of discounting. The record company gets about half of whatís left, and the artist about half. But, while the record company pays that six bits a copy, actually less considering a volume discount or doing it in-house, a lot of the promotion and expenses come out of the artistís share, which is how record companies make so much money."

"Looked at that way, that bites," Dayna said. "But youíre going to sell a lot more through stores and like that than through a record company."

"In theory," John said. "How much competition are you up against in the record stores? The only way to get a name made in the business is to promote yourself. You girls know who Jenny Easton is, donít you?"

"Sure, she had a big hit a few years ago, a remake of Fever."

"I know Jenny a little," John said. "Sheís a good example. Her first album, Smoke Filled Room, grossed somewhere around thirty million the first year, so in theory, she pocketed around nine million. In practice, about eight million in promotion came out of her pocket, and she was so new in the business she didnít realize she was getting raped. By the time everything was said and done, she was left with about half a million, and after the IRS got done with her, she was in the hole. She had to do a second album with a hell of a lot less promotion, but with sales riding on the first, to get her butt out of tax trouble."

"Shit, no," Dayna shook her head. "I never knew that."

"Point is, hitting it big doesnít mean hitting it big," John said. "But look at it from the other end. Recording and mastering and clearing music all cost money, but suppose you could do it on the cheap, no studio musicians, a little studio that will work with you, and maybe you can record a master for a grand or two. Then, you have a pressing company knock out a thousand copies for you, thatís seven hundred fifty bucks. For the sake of round figures, three bucks a copy for everything. Now youíre selling that dog for fifteen bucks."

"Whoo, boy!" Dayna said, impressed. "Thatíd be like twelve grand profit. Can you sell that many?"

"Sure can, Iíll sell two or three hundred here, Friday and Saturday nights," John smiled. "Cheryl will even have a woman taking the money from the customers, out of the goodness of her heart. On top of that, Iím getting a fee for performing in the first place. And, to make it even nicer, Iíll have four albums there and Iíll have paid the master costs on three of them; this isnít the first pressing of those. Those Iím getting closer to fourteen bucks apiece profit. Now, Iíll admit, the new album is a little more advanced, I got some good studio musicians in to back me up on a few tracks, but I figured I could spend the money this time."

"Holy shit, I never even thought about that," Dayna said, shaking her head. "Hell, thatís the same producer-direct-to-consumer shtick that we throw into hat lines all the time. Look, John, the guy who taught me the most I know about the business more or less retired from it before they came out with CDs, much less got popular, so itís understandable we donít know this. How about cassette tapes?"

"The price break ainít quite as good on them but still pretty good," he said. "On the other hand, tapes are on their way out. I have íem, but donít move them as fast, as a lot of my customers still donít have CD players."

"How do we get into the CD business?" Sandy asked.

"Oh, thereís a few tricks," John told them. "Studio time comes a little high but itís worth it. If you can pretty much go in, sit down and play what youíve got to play in a day or two, and you got somebody with a little studio and a good hand at mixing, you can get out of it without burning your ass too bad. You hear these stories of people spending hundreds of thousands of bucks on studio time; thatís because they rent the studio to do their rehearsing, record the shit over and over again, then spend a coonís age dinking around with the mixing. The big trick is youíve got to have your shit together before you step into the studio. That includes clearances, and thatís the other pain in the ass, especially for you two."

"Clearances? Iím not with you."

"A big chunk of the music you two do is material thatís already copyrighted. Technically, when someone gives you money to play something like Iíll Never Fall In Love Again, you owe a percentage to a record company. When youíre playiní on the street like you do, nobodyís gonna hold you to it. But you put that on a CD without clearing the copyright with somebody like Columbia or whoever holds the rights, theyíll have your ass in court so quick it ainít funny. Thatís why my CDs are all my own material; I donít have to piss around with clearances. They cost money, sometimes a lot of money, and sometimes theyíre a pain in the ass to arrange. It can take years."

"Shit," Dayna frowned. "I knew there had to be a fly in the ointment somewhere."

"There it is," John nodded. "Now, there are a couple things that might make things a little easier. First, you donít want to do a lot of covers on an album, anyway. One or two is fine, but mostly or even all covers is another story. So that means you want to do original works. Now, take Cold Cold Heart. Thatís Hank Williams, which means that itís owned by Acuff-Rose, and I know a guy over there who would probably clear it pretty cheap, especially since youíve turned it into blues. I liked that version you did of House of the Rising Sun, it doesnít sound much like the Animals. Did you rework that?"

"Actually, not much," Dayna told him. "The Animals reworked a traditional version that may be a hundred years old. I did the old version."

"Didnít know that," John said. "OK, if itís that old and you can prove it, and you do the original version, you could stand off a copyright claim, and you donít need clearance. Your renaissance faire stuff, thatís all old stuff like that?"

"Some of it," Dayna said. "Some is newer, and some we wrote ourselves. We did a lot of covers when we started; weíre trying to pull away from them to our own pieces, or at least major reworks, like Cold Cold Heart. Thatís the first song I did a major rework on, and Iíve honed on it a lot over several years."

"Sounds damn good, too, Iíd want to put that on an album," he nodded. "Thereís no reason your first album canít be a medley of this and that. Far as that goes, Iíve got a few songs that are your kind of music that Iíll never record, and a place like I work will never be interested in them, so Iíd clear them to you real cheap to help you get started. But I think you may have enough to get started, anyway, there was some stuff you did this afternoon that I never heard before. There was one that really struck me; for example, I think it was something about Genie in a Bottle, thatís pretty good. Is that yours?"

"Yeah," Dayna grinned. "We wrote it in the front seat of my old Chevette on the way up here last year. Thereís a dirty story behind it."

"Thatíd go pretty well on an album, I think," he grinned. "Tell you what. Letís get together tomorrow, and you do your original pieces for me. Iíll tell you what I think, what might work, what might not, what needs work. Itíll all be my opinion, of course, and itís for what itís worth. And Iíll think about it tonight to see if I can remember a few of mine that you might be able to work up."

"Fair enough," Dayna smiled. "How about recording and mastering and like that?"

"You going to be down in Tennessee anytime soon?"

"Weíll be doing a renfaire near Knoxville in October."

"Oh hell, by October I ought to be able to find someone in Nashville that can take you into a studio for a couple days for a reasonable fee."

"John," Dayna said. "I have to say youíve opened our eyes to possibilities weíve never even thought of, and we appreciate your offer of help. We must owe you something for it. What can we do?"

John grinned at them with a gleam in his eye. "Lookiní at the two of you," he said. "Fifteen years ago Iíd have had a different answer, but Iím married to the woman that was set on earth for me, and I ainít going to mess with that. So, hereís the deal. In a few years, youíll be around someplace and youíll find a talented kid needing some help. Youíll have been around the block a bit by then, so you can pass some of this stuff along to them, so they can pay it forward to the next person."

Forward to Next Chapter >>

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.