This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Chapter 6

Careful readers will probably notice that I didnít mention racing or the MMSA in the last couple of chapters, which were a quick summary of our first few years in Bradford. There was a fairly good reason for that: especially in the early part there wasnít any, and when it re-entered our lives, it wasnít much.

After I got out of the hospital back in 1954, Arlene and I kept my promise to Smoky Kern and went out to the track one evening for his season finale along in September. When Iíd been out there in July I hadnít really paid much attention to it Ė it was just another track among hundreds that Iíd raced at over the years. This time, I took a little more notice of it. I think I said before that the place was dirty and beat-up; I doubt that there had been a drop of paint used there in the last few years.

There were, I would guess, about forty or fifty cars racing that evening, and the stands were fairly full, even though it was nothing like a standing-room-only crowd. Just going from my mindís eye, Smoky must have lifted around a thousand tickets that evening, give or take.

Smoky was running just one class of cars, jalopies Ė prewar cars that were in theory supposed to be more or less stock, but there was little restriction to what you could do to the inside of the engines. The cars were almost all Ford V8s, and as long as you had a flathead Ford engine in there it was fine. There was no telling what went on inside that engine and nobody checked Ė you could have it bored out, the heads milled, a hot cam installed and stuff like that and nobody cared. What you couldnít do was do something to the outside of the engine that made it look like it wasnít stock Ė in other words, no multiple carbs, no exhaust headers, no Ardun overhead valve conversions, stuff that was cheaper and easier than working on the inside of the engine. Since the cars were mostly junkers anyway, the system more or less worked.

Since it was all one class, Smoky ran a complicated series of heats and A-, B-, and C-Mains that mostly ensured that everybody got on the track at least a couple times over the course of the evening and most often more. Since the payout of the purse was nothing much, most people were there for the fun of racing and maybe beating somebody, so it worked. It wasnít very different from anything Iíd seen in lots of other places.

The racing was pretty good even if it was pretty rough and tumble. It really seemed rather primitive compared to the fast, slick midgets that Arlene and I were used to. I think both of us agreed that while it was interesting, it really wasnít that interesting compared to what weíd been doing.

While Iíd been in the hospital weíd pretty well talked it over and agreed that we were going to have to turn our backs on racing, and especially on the MMSA, and thatís what we tried to do. It was easy at first, since the season had ended at the Bradford Speedway not much interested us there anyway. Frank and Spud had brought my extra clothes and a few things down to the hospital while I lay unconscious, but after that we didnít hear a thing from them. I think both Arlene and I figured on hearing something after the end of the season, or maybe a Christmas card, but there was nothing. When the first of April came around I figured weíd get a call to see if we were interested in going out on the road again. By then it would have been fairly easy to say no, since we were buying the house and settling into our jobs, but again, we heard nothing.

In fact, we heard nothing either from or about the MMSA after that. We purposely didnít read any racing publications like the National Speed Sport News, so that probably had something to do with it. Racing news of any other form was just plain nonexistent in any other media we had in Bradford, with the exception of the really tiny box ads in the Bradford Courier once the racing season opened out at the Speedway again. In fact, we only heard a couple of pieces of racing news all the next summer Ė that Bill Vukovitch had died while leading the Indy 500, and about Pierre Levegh crashing his Mercedes SLR into the crowd at LeMans, killing eighty-two people in the process. This was only about a three-day wonder of news in the US, and that was about it for news we heard.

That was in the days before most houses were air conditioned, and on a hot summer evening we used to go sit on the front porch to stay cool until the mosquitoes drove us in. If it happened to be a Saturday night and we didnít have a fan blowing on us to keep them down, sometimes we might hear the roar of the cars from the speedway across town, but more often not. We were shielded by the trees and a hill, and everything had to be perfect for us to even hear a bit of the rumble. Once or twice I thought it might be fun to go check things out, and later Arlene admitted that sheíd thought the same thing from time to time, but mindful of our decision to turn our backs on racing, we never mentioned it to each other, and never went.

In the years after that it was something even further out of mind, since Arlene was pregnant with Vern the next summer, and then we had small children that made us not want to take excursions if we didnít have to. I think having the kids made us both realize that it was a good idea to stay away from racing, so we did. Arlene and I didnít even talk about it very often.

Things changed a little when we moved out to the farm. Now there wasnít a hill and much of town between us and the race track, only a couple miles of open country, and we could hear the races a lot better. On quiet nights we could even make out the PA system between races if everything was perfect Ė well, we could hear the sounds but couldnít make out what the announcer was saying. A couple times Arlene and I agreed that it might be fun to go down and check it out, now that several years had passed, but again the prospect of small kids getting antsy kept our enthusiasm down.

There were a few weeks in the summer of 1962 that I switched a few things around in my driverís education schedule. There were some kids with day jobs in the summer, and the only time they could drive was in the early morning. So, for three or four weeks there I had kids driving from six to eight in the morning, with the next schedule not starting till nine, so I had an hour to kill each morning. I got in the habit of going into Kayís Restaurant downtown for a cup of coffee and maybe a light breakfast.

One morning I was sitting there minding my own business, and discussing the dismal prospects of the Cubs with Lloyd Weber, whoíd been the publisher of the Bradford Courier for about ten years. I was really more of a White Sox fan, especially after the great year theyíd had in 1959, but then I really wasnít much of a baseball fan at all.

I should probably explain that while Bradford is in Michigan, itís far enough west that itís actually a little closer to Chicago than it is to Detroit. In those days of TV antennas, we received the Chicago TV stations a lot better than we did any from Detroit, although the stations from Kalamazoo, Fort Wayne and South Bend came in quite a bit better. So it was that Bradford was, and is, right around the dividing line between Detroit fans and Chicago fans, with maybe a slight lean toward the latter. When it came to college football, weíre a lot closer to South Bend than Ann Arbor, so Notre Dame is the hometown big school, not the University of Michigan. Although Iíd spent a fair amount of time in Livonia, which is on the edge of Detroit, Arleneís family being from Schererville meant that I now spent a lot more of my attention focused on Chicago than I did on Detroit.

Along about the time that Lloyd and I exhausted whatever interest we had in baseball, Smoky Kern wandered in, looking for a cup of coffee. Lloyd had to head back to the paper, so Smoky and I got to talking.

By this time, Smoky and I werenít exactly strangers, although we werenít what you could call friends, either. We probably said hello to each other half a dozen times a year at one event or another, and maybe once a year we would talk a little more. Oh, Iíd ask him out of courtesy how things were going at the track, and heíd say, "slow" or "all right" or once in a while even "pretty good," but we never got down to details. I hadnít really seen him to talk to him for a while, so I asked him the usual question again, and got back, "Oh, not too bad."

I guess I was in a mood for a little more conversation than I usually was with him, so I asked him, "Are you still running jalopies out at the track?"

"Not really," he replied. "How long has it been since youíve been out there?"

"Itís been a while," I admitted. "Has to have been six, seven years now."

He shook his head. "Things have changed a lot in that time. Back in those days we ran all one class of jalopies. I donít know if youíve looked around the junk yards much recently, but you just donít hardly find any prewar Fords out there anymore. The ones that havenít been used for racers have all been cut down for scrap."

"Hadnít really noticed," I said. "I havenít really spent any time looking for prewar Ford parts since I got done fixing up my í37 Ford, and thatís been a while ago. But now that you mention it, finding parts isnít as easy as it once was. So, what are you doing now?"

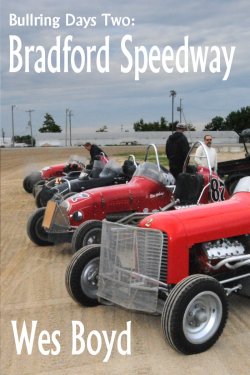

"Weíve got several classes out there, not just the one," he explained. "The hot class is the modifieds. Thatís any closed-top chassis before 1948 with the fenders off. Any body modifications are allowed, and any engine so long as it came out of a car, is under 400 cubic inches, and not supercharged. Itís still pretty much the same cars as the jalopies, but a lot more modified with a lot more work in them. Theyíre faster than snot. You canít really point at one engine being superior because thereís a lot of good ones."

In those days we were starting to get into really big engines with really big power. "How much power do they get out of those mills?" I asked.

"A whole pot load," he replied. "Of course, everybodyís lying through their teeth about what they have, but it wouldnít surprise me if some of those guys were pulling 500 horsepower if you put the engine on a dyno."

"Good grief," I said. "No wonder I can hear you guys from my back porch two miles off."

"Yeah, we donít have a lot of the real hot cars, but the ones showiní up do flat shake the earth when you light them up," he said. "Then we have the Sportsman class; thatís stock bodies although gutted out, 1955 or before, V8s to 300 cubic inches. We still have a few Ford flatties running in that class, although the í55 Chevys are starting to run them off."

"Understandable," I agreed. "Thatís one sweet little engine."

"It is, indeed," he replied. "Thatís our biggest class, but itís still small enough that we can get everybody into an A-Main and a B-Main and look a little sparse in the process. Then we have our Junior Stocks, which I donít know if itís the wave of the future or a pain in the ass."

"Howís that?" I asked.

"Well, itís an economy class," he explained. "Back when we ran jalopies, it was no great trick for a high school kid with fifty bucks in his pocket to get a prewar Ford, gut it out and run it in a race with the stock engine, maybe warmed up just a little. Usually the kids werenít going to win anything that way, but when we were running C-Mains they at least got into a feature with a shot at winning. Some of the hot jalopies had quite a bit of engine work done under the hood, and, well, they were just better. But, when the supply of prewar Fords began to run out and we started the Sportsman Class, well, you donít buy a í55 Chevy for any fifty bucks unless itís been wrecked too bad to race anyway."

"Yeah, I can see that," I agreed. "Since Iím the driverís ed teacher I know there are some fifty-dollar cars left out there, but theyíre not going to be anything like a í55 Chevy."

"Right," he nodded. "So, I got to thinking that if we donít have a place for kids to start out racing, weíre not going to have anybody racing at all in a few years. I got together with some of the people running tracks around the area, and we came up with the idea of the Junior Stocks. This is for closed cars at least ten years old, stripped out, stock tires, and a stock six-cylinder engine. Thereís an age limit on it, the drivers canít be over twenty-one."

"Sounds like a good idea," I nodded.

He shook his head. "Well, I thought so at the time I thought it up," he said. "The problem is that I forgot that kids are kids. Whatís worse, parents are parents. You get kids out there that are stone rookies that havenít even had driverís education yet, and you get some kids that are pretty good. Youíve got cars that are really junkers, I mean not even up to stock, and some that are so hotted up illegally that they could run with the Sportsmen and do a good job. Worst of all, youíve got a few kids that are so full of piss and vinegar that theyíd wreck half the field to win a twenty dollar payout. Theyíre driving the beginners right out. Somebody needs to ride herd a little closer on that class than I can. I got too much else to do to have to deal with them, too."

Now, I donít want to imply that I didnít see the fish hook in that statement. In fact, I wouldnít have been surprised if Smoky hadnít showed up at Kayís just to drag that past me. Smoky knew that I wanted to stay away from racing Ė in fact, Iíd told him that the first time Iíd met him, and the subject had come up since. This wasnít racing, it was being an official. Since it was working with kids and I liked working with them, it had some appeal. Much though Iíd tried to stay away from it the last few years, I knew that it was laying right there under the surface, an itch waiting to get scratched. But I decided that I wasnít going to be that easy a sell. "Yeah," I nodded. "It sounds like you need someone to keep an eye on things."

"You know," Smoky said like heíd just thought of it, "You might do pretty well at keeping things under control. After all, most of the kids know you, and they know that you used to be a hell of a racer."

"I wouldnít say that," I said defensively. "I mean, Iíve never bragged about it, but Iíve never hidden the fact that I used to do some racing, either. Sometimes I can pass something along from what I learned about it."

"Think about what some of those kids could learn about racing from that experience of yours," he pointed out, jigging the bait in front of my nose a little.

"Smoky," I shook my head, "I know what youíre trying to do. It sounds like it might be interesting, and I could maybe even do a little good at it. But Iím not going to tell you right now that Iím going to do it. I need to think about it some, and I need to talk it over with Arlene. She used to like hanging around race tracks just as much as I did, and Iím not going to commit to doing it without talking it over with her."

"Tell you what," he said. "Come on down Saturday night. Iíll give you two a pit pass. You just hang around and see what Iím talking about, and see if you think you can do something about it."

"Like I said, Iíll think about it," I told him. "Iíll admit, it sounds interesting."

"Canít ask for anything more than that," he agreed. By then I think he knew he had a pretty good chance of having me go along with him, and any more pushing might oversell me. He changed the subject, or at least changed his tactics. "You ever hear anything about that midget group you use to run with?"

"Nope," I told him. "Not a thing, not since they left me here years ago."

"Kinda wondered about that," he said. "I havenít heard anything about them in years, either. Back a few years ago we used to get a mailing from them now and then looking to schedule a date, but itís been years now since I heard anything. I wouldnít mind bringing in a special show some time, but things are a little different these days since we depend on the back gate a lot more than we used to."

"Howís that?" I asked.

"Well, we donít get the crowds we used to," Smoky explained. "I canít tell you the last time I saw the stands all the way full. It used to be that I could cover expenses and make payouts out of the front gate, but over the years Iíve had to charge more for entry fees and pit passes to make up for the lack of the crowd. Too many people would rather stay home and watch TV on a Saturday night than come out to the track and have some fun. What it means is that things are tighter than they used to be, not that they was ever loose."

"It might be that youíre cutting your own throat on that," I said. "Seems to me that bringing in a special show and advertising it might bump the front gate up a bit, even if you have to raise ticket prices a little to cover it."

"Might be," he replied. "Iíve thought about it some. Itís a damn fine balancing act. I ainít in the business to lose money. I donít make much at it, and I canít afford to lose any of it."

"I guess thatís kind of the way it is," I said. "Iím afraid I canít help you any with getting hold of the MMSA. They could be long out of business for all I know. I know that when I left, Frank and Spud seemed to be getting a little tired of it, but like I said, I havenít heard a word since they left me here. I donít know whether I care about that or not."

Actually, in a way I did care, but I wasnít going to let Smoky know it. After all the years I had put in for Frank and Spud, you would have thought that Iíd at least get a Christmas card or something. Frank might not think of it, but I didnít think Vivian would forget something like that. But who knew what had happened after Arlene had talked with Frank and Spud the last time?

"Well, life moves on, I suppose," Smoky shrugged, and drained his coffee. "I got to get back to the store. You think about what we talked about. If you want to do it weíll work it out somehow."

"Iíll think about it," I promised. "And Iíll talk to Arlene."

"Canít ask for much more than that," he said as he got up. "You take care, now."

As Smoky headed for the door, and presumably back to the auto parts place he owned, I glanced at the clock on the wall. It was time to be heading back over to the school, so I headed out to the Chevy and pointed it that way. The Chevy had become my car when weíd bought an Olds F-85 for Arlene after we moved to the farm. The Chevy was starting to show some signs of age, and probably wasnít worth a whole lot on a trade-in. After the discussion with Smoky, though, I got to wondering if it might not make someone a pretty good Sportsman with a little bit of work. It might be fun to go out and race a little now and then, I thought Ė maybe not make a habit out of it, but occasionally go work the kinks out a little. It was a tempting thought, and it reminded me just a little that there was still some racer in me lying under the surface, waiting to get out again.