|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

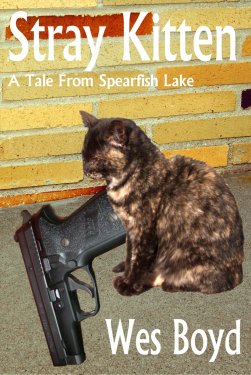

Only a millisecond or so passed in the time it took the semi-wadcutter bullet to drill through its target and its impact with the heavy steel plate behind it. As it was designed to do, the plate deflected the bullet downward into the sand trap, where it came to a stop rather more slowly than at its start, accelerated to a near-supersonic speed by the powder charge in the cartridge. The whole flight of the bullet took only a fraction of a second from the time it left the barrel of the Sig Sauer P226 held by Cody Archer, until it came to a stop and became scrap metal that would eventually be recycled.

Something less than a second later a second bullet followed the first, the shock wave of its passage masked by the rapid expansion of the gases formed by the burning powder, which put it on a trajectory almost identical to the first. A semi-wadcutter bullet is designed to make as small an entry hole as possible as it penetrates a paper target so that scoring is made a little easier for competition. The second bullet didn’t quite go through the hole left by the first, but overlapped it to some degree, elongating it just a little as it penetrated the paper of the target.

Another followed, then another at the rate of about one per second until there were ten holes in the target, all but one in the center ring, and that one not far outside. Cody then set the pistol on the table and stepped back, signifying that he was done with his shooting. In the relative stillness that followed the fierce noise of the pistol being fired, Gil Evachevski said formally, “Cease firing.” Though Cody had been the only one shooting, Gil was a stickler for range safety procedures being strictly followed. It had become automatic for Cody and the others standing around in the indoor range of the Spearfish County Sportsman’s Club a couple of miles outside of the town of Spearfish Lake.

Cody pulled off the large red ear protectors and said softly, “Damn it.”

“Looked pretty good from here,” Sergeant Charlie Wexler, second in command of the Spearfish Lake Police Department, said conversationally as he took off his own ear protectors. He only had to fire for qualification once a quarter, though he liked shooting enough that he often stopped while on duty on quiet Thursday evenings to run a few rounds through his .40-caliber Glock ‘just to clean the spider webs out’ of his normally immaculate weapon.

“I had a flyer,” Cody replied in evident disgust as he punched the button that would bring the target back to the firing line. “The fourth round went just absolutely apeshit on me.”

Charlie took the statement with a grain of salt. He knew that Cody’s “absolutely apeshit” would have been considered “pretty damn good” by any members of the Department, including himself. At seventeen, Cody was less than half as old as Charlie, but he knew that Cody was a terrific shot – maybe not National or Olympic class, but close enough that it was within reach of it. Several times he had invited Cody to stop by when the cops shot their quarterly qualifications. He’d first out-shot everyone in the department at the age of thirteen and had never missed doing it since.

The indoor range was a long, narrow building, and not well heated. It was chilly, perhaps in the fifties, but that was considerably better than the subfreezing wind outside on this mid-December day. It didn’t take long for the powered pulley and rope arrangement to bring the target back to the firing line. Cody, a thin, reedy teenager just under six feet, pulled the target down and glanced at it. “Look at that,” he snorted, and pointed at the arrangement of holes in the target – most of them were overlapping in the X ring, the center, but one split the line between the 8 and 9 rings. “A flyer, just like I said.”

“Yeah, that one got away from you, all right,” Gil smiled. “You think maybe your sight picture was all right?”

“I think so,” Cody shook his head. “The only thing I can think of is that I must have gotten that one off a little too quick.”

“Could be,” Gil shrugged. He knew there were any number of things that could have gone wrong – in nearly sixty years of competitive, recreational, and, since he was a retired Army Sergeant Major, professional shooting, most of them had happened to him at one time or another. In that long history, he’d occasionally come across people who were naturally good shots, just plain inborn talent, and Cody was one of them.

For the last twenty years, Spearfish Lake had been a hotbed of dogsled racing. There were four people from the town who had run the 1100-mile Iditarod race in Alaska, and one of them was Cody’s mother, Candice. Back when she had been getting ready for her first run of the race a few years before, Candice had been warned that she needed to carry a heavy pistol with her in case she happened to meet a dangerous moose along the trail. It had been known to happen, and had happened to another Spearfish Lake musher, who had to shoot the moose to save her team. Candice had grown up a farm girl and had shot rifles and shotguns a little so wasn’t afraid of them, but had never fired a pistol, let alone a heavy one. She went to Gil to help her out. At the time Candice felt that she was shorting the kids on her attention a bit, what with all the other preparation going on, so when Cody expressed an interest she brought him along.

Gil started Candice out with a .22-caliber revolver for the sake of getting her used to the mechanics of handling a pistol without having to deal with the recoil of the heavier pistols at first, and Cody was paying attention. After his mother had gotten comfortable with the .22, Gil asked Cody if he’d like to try it out. Cody agreed that it might be kind of fun and gave it a try. Gil expected that the kid would scatter .22 rounds all over the end of the building, so was more than a little surprised when Cody put nine out of nine in the black, which was better than his mother had done. Gil loaded the revolver again, gave the kid a few tips, and now that he’d gotten over the first time jitters, Cody shot even better. “You like this, kid?” Gil had asked.

“Yeah,” Cody smiled. “If I was to practice, do you think I could get to be any good at it?”

Over the years he’d spent a lot of time with Cody, working off his rough edges, developing his talent to where he was one of the top pistol shots in the region in any age group; he wasn’t far behind with a rifle, either. He had the potential to be even better, but he could only practice so much since ammunition was expensive. At that, Cody did the majority of his shooting with a .22 pistol, for which ammo was much cheaper, but Cody occasionally shot in large-bore competitions so he also tried to keep in practice with the nine millimeter. Gil thought that Cody had the potential to go even further with his shooting if he were able to practice ten times as much under the supervision of an even better instructor than Gil was. “You want to go again?” he asked his young protégé.

“Not just now,” Cody demurred. “I want to talk with Charlie for a minute before he gets out of here.”

“All right,” Gil smiled, and turned to Bob Nyswander, who had been waiting to shoot for a while. There were few enough people around that it was no big deal to fire one at a time, which made for less distraction. “Bob, you’re up.”

“OK,” Bob replied, getting up from one of the beat-up old kitchen chairs that were scattered around the back of the room, and coming to the line where his M1911A1 .45 was resting. Despite its design nearing a century old, there were plenty of people around who thought the old Army automatic was the best pistol ever made and Bob was one of them.

“Hey, Cody,” Sergeant Wexler spoke up. “Why don’t we head out to the car so we can talk while he’s trying to knock the walls down with that thing.”

“Suits me,” Cody said quietly to Charlie, who was several inches shorter than Cody, about as thin, and going bald, which he covered up by keeping his hair in a very short butch cut. “Let me grab my coat.”

At least partly because Cody had school the next day, it had long been agreed to keep the Thursday night sessions at the range on the early side. This close to the Winter Solstice, the sun had set long before, such sun as there had been on this overcast, gray northern Great Lakes day. There was no snow on the ground, which was unusual for this time of year; while there had been a heavy snow in November, there had been some unseasonably warm days since then. The weather forecast wasn’t calling for snow this evening, but if the forecast had been wrong it wouldn’t have surprised Charlie any.

Charlie’s patrol car sat perhaps twenty yards from the door of the range, but it was no problem to find since the parking lot was lighted by a mercury vapor yard light. Cody was right behind Charlie, and went to the far side of the car, where he opened the front door and got in as Charlie got in the far side. “Thanks,” Cody said. “I wanted to keep this between you and me.”

“Problems?” Charlie asked as he closed the door. Although the car had just been sitting and had cooled off, it felt good to be out of the wind. Over the years he’d gotten friendly with Cody, mostly at the range, but occasionally elsewhere. Charlie knew that Cody was a good kid – but he was also a kid who could be trusted to tip him off if he thought something was wrong. There weren’t many kids who did that, even in a town as small as Spearfish Lake, so Charlie had understood from the beginning to keep the fact that Cody was a useful source of information confidential. Several times the two had talked about Cody becoming a cop; the kid was undecided about it but often seemed to be leaning in that direction.

“I don’t know,” Cody sighed as Charlie started the car to get some heat going. “Do you know Janice Lufkin?”

“I don’t think so,” Charlie shook his head. “Is she any relation to Jack Lufkin?”

“His daughter,” Cody told him. “Bobby Lufkin is her older brother.”

“I guess I know who you’re talking about,” Charlie nodded. “I’ve seen her around, but I don’t really know her. Her father and brother are trouble looking for a place to happen, though.”

“No fooling,” Cody agreed. “I’ve known Janice since we moved up here years ago. When I first knew her, she was an OK kid, nothing particularly special, but a good kid if you know what I mean. Ever since her mother died, it just seems like everything has gone to hell for her. I mean, it’s like she just doesn’t care, but worse, if you know what I mean.”

“Sometimes kids have trouble accepting something like that,” Charlie observed, feeling that Cody had more to say but not wanting to have to dig it out of him.

“Well, yeah, of course,” Cody replied thoughtfully. “But you’d think that she’d be getting over it by now. But it seems to be getting worse. She’s very withdrawn. She always was shy, but now it’s worse than ever. Something else is going on. She never was an outstanding student, but at least a good one, but this fall she’s on the verge of flunking everything. Several times this fall she’s come to school with bruises, or limping, or obviously hurting.” He let out a long sigh and continued, “We have chem lab together, and today I noticed that she had her hair all combed down over one side of her face. I tried to look like I didn’t notice, but several times I could see that she had makeup on that didn’t quite cover that she had a black eye. And she was moving very stiffly, especially her right arm. And now, she’s missing a couple teeth.”

“You think someone’s been hitting her,” Charlie concluded.

“No, I know someone’s been hitting her,” Cody said flatly. “She hasn’t said anything to me or to anyone else that I know of. I did ask her if everything was all right, and she said, real weakly, ‘Yeah, I guess,’ like it really wasn’t, but she didn’t want anyone to know.”

“Do you think it’s her father or her brother?”

“I can’t prove it, because I don’t know,” Cody shook his head. “But if I had to guess, it wouldn’t be real hard.”

“Have you told anyone at the school about this? Mr. Hekkinan, or anyone?”

“No,” Cody said. “If that’s what’s going on I don’t want to make it worse for her. I’m not sure the people at the school would keep me out of it. I decided to hold off till I saw you tonight, because I think you can do better than they can.”

“I’ll look into it,” Charlie promised. “She’s about your age, right?”

“I don’t know for sure, but she’d just about have to be,” Cody replied.

“Good,” Charlie said. “That means that we can get Protective Services involved. But if she’s not coming forward about it, it would sure be nice if we could talk to someone who had a little more knowledge of what’s going on. Does she have any friends she might have told about it?”

“I doubt it,” Cody shook his head. “If she has any friends at all it’d be news to me.”

“That’s sad.”

“Yeah, it is,” Cody agreed soberly. “Like I said, she used to be a pretty decent kid, but things seem really screwed up for her now.”

“I’ll see what I can do,” Charlie said. “Since we don’t actually have a valid complaint right now it may take a little while, but thanks for letting me know.” He shook his head and sighed, “Cody, she does at least have one friend who cares enough to let me know about it.”

“Yeah,” Cody said glumly. “I guess.”

“Go in and blow away some more X-rings,” Charlie grinned. “That ought to make you feel better. I’ll do what I can for her.”

As it turned out, Cody only ran another couple clips through the P226 over the next hour or so. He knew what his problem had been with the flyer earlier – he’d been unable to clear the vision of the obviously desperately unhappy girl from his mind, and after he’d talked with Charlie, his lack of concentration was worse, rather than better. After sitting back and running through some mental exercises Mr. Evachevski had taught him to clear his mind, he wound up shooting about like he had earlier. But he felt like he was working at it, trying to keep his thoughts off Janice and her problems; the shooting wasn’t coming easily.

After the second clip, he decided that wasting his ammunition wasn’t helping anything. He had a box of shells that was getting low, so he filled both of the clips so he could throw the box away, and then decided to hang it up for the evening. He told Mr. Evachevski and everyone good night, and headed for his car.

Since Cody was under the age of eighteen, he didn’t have a concealed weapons permit. He could, however, carry a firearm if it was locked in the trunk of his car, so he put the P226 and the clips in the padded carry box he used and loaded it in the trunk.

The car wasn’t actually his; technically, it was his mother’s, although to his knowledge she hadn’t driven it in a while. The Archer family wasn’t rich, but neither were they poor. Cody’s father John had grown up in Spearfish Lake, but had met Candice at college. He’d taken an accounting job in Camden right after graduation, then after Shay and Cody had been born had moved to a bigger and more rewarding job in Decatur, hundreds of miles to the south; with the kids in elementary school, Candice had taken a bookkeeping job in a bank. Then, not quite six years before, both jobs had blown up in their faces within days of each other, at a time that the local school system had decided to send the distinctly middle-class Shay to a slum junior high farther away. It seemed like a real good time to get out of Decatur, and that’s what the family did, mostly because John happened to find out that the owner of a Spearfish Lake accounting firm was looking for someone to buy him out.

They sold their place in Decatur and bought a house in Spearfish Lake, moving just as soon as school was out. John’s office was only about three blocks from the house, so he often walked to work; later that first summer Candice went to work for Spearfish Lake Outfitters, owned by John’s younger brother and sister-in-law, right next door to his office. That meant that they could get along with one car, a minivan, and in the nicer part of the year it sometimes went days without being used. That meant saving a lot in car expenses since income was a little limited due to the need to pay off the purchase of the accounting agency. It was only as the boys approached driving age, that the need for a second car came along, and for some reason Shay seemed to consider the Escort his car.

There had been a bit of a hassle the previous summer when his older brother Shay headed off to Lake State University – he’d planned to take it with him, even though cars on campus for freshmen were not encouraged. It was clear that Cody and his mother were still going to need the car in Spearfish Lake, so it had finally been worked out that if Shay kept his grades up in his first year there could be some consideration of a car the following summer. Shay was due home in the next few days, so presumably there was going to be some talk about who got to use the car then, especially since his girlfriend Bethany Frankovich was going to be home from Grand Valley State.

Cody figured he could get along for a few days over Christmas, and figured he could drive the minivan if he absolutely had to. It wasn’t as if he had a bunch of friends to hang out with at every opportunity, because he didn’t. His father had pushed school athletics at both the boys rather hard, and Shay had been the one who took to them, ending up with twelve letters in school sports and a lot of time on the bleachers for his parents. He always seemed to be hanging out with a group of loud, rough friends, and while he was a solid athlete his grades had been rather marginal.

Cody had been a considerably different kid: quiet, almost shy, something of a loner with no real close friends his age. Shay was about his closest friend, and it seemed lonely with him gone. Cody was a good student, mature for his age, and nothing much of an athlete, at least in school terms. He was the one who got the strikeouts in Little League, while Shay got the home runs. It had been Cody’s talent and inclination toward shooting that got his father off his back about athletics. His mother had made the observation that while they might sit in college stands and watch Shay play football, it didn’t seem unreasonable that someday they might be sitting in the stands in the Olympics while Cody shot. That still seemed possible, although Cody doubted it would happen anytime soon.

Very few people around Spearfish Lake were even aware of the fact that Cody was a competitive shooter. This was partly because Cody wasn’t the sort of kid who bragged about himself. More importantly, it was because in even such a northwoods place as Spearfish Lake, where hunting was accepted and encouraged, there were a lot of people who were a little afraid of the idea of kids messing around with handguns. Cody never, ever, carried a gun onto school property, even in the trunk of his car. A couple years before, two high school kids had made plans to go hunting after classes, and without thinking about it had taken shotguns to school in the trunks of their cars, something that was perfectly legal. However, somehow a comment was made about it, somebody else misread it, and all of a sudden every cop in the county was surrounding the place and the kids were taken off in handcuffs, never to return to the school. That was a lesson that Cody took to heart.

Cody wasn’t thinking about that as he put the box with the P226 and the loaded clips into the back of the aging Ford Escort. His mind was still on Janice. He realized that he’d crossed a sort of divide when he told Sergeant Wexler about what he’d seen earlier that day. He was mostly concerned that he’d poked his nose into something that, when he got right down to it, wasn’t really any of his business. Still, he was concerned about her and hoped that Charlie would be able to do something about it – at least find out what was going on. The problem was that, as far as he could tell, Charlie didn’t sound too hopeful that anything could be done unless there was a little firmer evidence. Hell, Janice could be getting beaten up again right now, be getting killed, and no one would know about it.

He’d tipped off the police about his suspicions, and he had hoped that would be enough, but right now, it didn’t feel like it was. In fact, it had seemed like that all evening, but what else could he do? As he got in the Escort, there was something stirring in his gut that was telling him that it wasn’t enough, something he couldn’t put his finger on.

It was chilly in the Escort, but at least it was better out of the cold wind blowing off the lake. Cody knew that he’d be just about back to town before there could be any heat expected from the heater, and that he’d never be able to get the car warmed up before he got home. There really wasn’t much of anything to do but go home, anyway; like a lot of small towns there isn’t a lot for kids to do but stay home and watch TV or play on the computer or video games, most of which Cody didn’t care for. Though it was only a short distance home, he replayed the conversation with Charlie Wexler in his mind, turning it over and over, trying to see what Charlie was really saying. From his viewpoint, what the sergeant had mostly said was that he was going to need more evidence if he was going to do something for Janice.

As he drove up the gravel road heading toward town, Cody flipped it over in his mind. What could it hurt if he was a little snoopy? He probably would find nothing, but at least if he looked he wouldn’t feel guilty about not checking if something were really happening. It wasn’t far out of the way, he thought. Might as well do it.

Spearfish Lake is a small town, and in small towns, people often know each other better than they do elsewhere. Cody was aware of where the Lufkin house was; in fact, for various reasons Cody knew where most of the kids in his class lived, at least if they lived in town, although he was a little vague about some who lived out in the country. It was not far off his route home, only a couple blocks out of the way, and only a few blocks from his home. It backed up to the railroad tracks that led to the Camden and Spearfish Lake yard and office – not the worst part of town, but well down in the lower half, he thought. The houses were old, and some were on the shabby side, with cracked paint, cluttered yards, and the occasional broken window patched with plywood or cardboard. In other words, it was about like the neighborhood where Hopkins Middle School in Decatur had been located, where the Decatur schools had planned to send Shay for seventh grade. He remembered it from when his parents had driven past it all those years ago; it was mostly a black neighborhood, and he remembered that it had scared him. At least this neighborhood was as white as the rest of Spearfish Lake.

Slowing to a crawl, he drove past Janice’s house. There was nothing untoward visible from the outside, but somehow that hard spot in his gut was even harder – somehow, some way, something didn’t seem right, but again, nothing he could put his finger on. Once again, the thought that it wasn’t any of his business crossed his mind, but at the same time he realized it would be best to put his mind at ease, if he could. If something really was happening and he didn’t check, he knew the guilt he felt would be overwhelming. At the next corner, he took the extra width of road to make a U-turn, then drove back up to the street, stopping a couple houses away so he wouldn’t be quite as conspicuous.

When he got out of the Escort, the wind was no less cold than it had been earlier, his sense of foreboding was even stronger, if that were possible. Walking quickly up the cracked sidewalk, he came up to the house, and looked into the front window. He could see nothing, but he could hear muffled yelling coming from inside. He couldn’t make out the words, but he could make out voices – male voices.

Realizing that the hard spot in his gut had been there for a reason, he quietly went up the steps onto the porch to get a better look in the window, noticing that the inside door stood open a crack, like someone hadn’t taken care to shut it. Peeking around the edge, he saw that his suspicions had been confirmed: Jack Lufkin was holding Janice down on the floor, a shotgun by his side, while Bobby was raping her.

Holy shit, he thought. I’ve got to do something.

Two guys, at least one gun. I can’t just go charging in there.

Call the cops, he thought. Charlie might not be far away.

In a couple running steps, he leaped off the porch and ran for the car. Cody was rare in this day and age that he didn’t carry a cell phone with him wherever he went. Reception was often lousy, and he wasn’t the kind of guy who had to be yapping with his buddies every instant. However, there was a cell phone in the car, kept there for emergencies, and within seconds he’d pulled it out of the glove box. He pushed the “on” button – but nothing happened. No lights, no nothing, dead as the proverbial doornail. The thought that it might help if he charged it once in a while crossed his mind. Frantically, he looked around the neighborhood – the nearby houses were all dark, except for the Lufkins’. He was at the car, he could drive somewhere but that would take time, and right now he didn’t think he had time.

There was another alternative, one he’d obviously been trying to avoid – the P226 was in the trunk, with a couple of loaded clips. Right at that instant, it seemed like the best alternative. He punched the button on the dash to pop open the trunk, dashed back to it, opened the gun box and pulled out the pistol. He jammed one clip into the receiver, shoved the other into his coat pocket, and chambered a round and as he ran back toward the Lufkin house.

He ran up onto the porch, and hardly slowed as he opened the door. “Get off of her!” he yelled as loud as he could.

“What the fuck?” he heard the older man yell. “Get out of here!”

“Get off of her,” Cody repeated, as he raised the gun into his normal two-handed shooting stance and fired a round somewhere toward the ceiling to make his point. Janice’s father didn’t get the message; he was diving for the shotgun on the floor even before Cody could speak. In an instant, Cody got a sight picture on his forehead, and his finger squeezed the trigger. The P226 barked, and the impact of the bullet threw the older man backward.

Janice’s brother Bobby had also been diving toward the shotgun and was almost there. He had a hand on it when Cody shifted his sight picture and squeezed off another round.