|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

The Spearfish County courthouse is a historic structure over a hundred years old, built of local fieldstone in an era when labor was cheap. Even though it was a big and majestic building, standing several stories tall, it was actually a little cramped, since the things that had to be done around the courthouse had expanded over the passing decades. Over the years several county functions had been moved to a newer building across the street.

The main courtroom was still large enough to serve the needs of the county. Although well maintained and neat, it bore the stamp of being as old as it was in a number of different ways. There were few decorations on the wall, except for photos of past circuit court judges who had occupied the bench. More importantly, the seats in the courtroom were hard wooden benches that made the most severe church pew seem comfortable. It was how things had been done when the building was built, and over the decades no one had ever seen the need to depart from tradition in spite of complaints ranging back over a century.

Although they’d gotten there plenty early, neither Janice nor any of the Archers were very comfortable sitting in the courtroom waiting for things to get under way. Candice thought that Janice looked especially uncomfortable, perhaps worried as she sat close to Cody, again holding his hand.

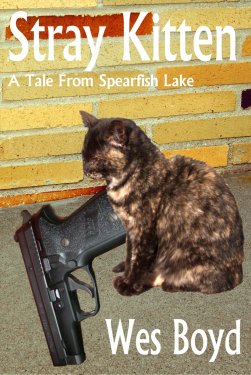

In truth, Candice was more than a little impressed with her younger son. Although it had been a little upsetting to find the two kids sleeping together, especially with the .357 on the bed stand, once Candice woke them up a little later things quickly made a lot of sense. Janice reported that she had slept the best she had since the whole affair had started. “I really don’t remember any more dreams at all,” she explained once she’d woken up a little. “But I knew that Cody was there to protect me in my dreams, so if I had any, they didn’t bother me.”

Candice couldn’t help but wonder where Cody had come up with that little bit of drama with the revolver, but it had certainly settled Janice’s mind. Really, it was a little uncharacteristic for Cody, who had tended to be something of a loner, but it was clear that he had taken some unexpected responsibility for Janice. Still, Candice wondered where this was going to lead, and seeing the two of them in bed hadn’t quelled her curiosity any.

“All rise,” the bailiff called. “Probate Court for Spearfish County is now in session.” Along with the handful of others in the courtroom, the Archers and Janice got to their feet – in Janice’s case, with the help of her cane and Cody’s strong arm helping her to stand. Wearing his black robe, Judge Robert Dieball came out of his chambers and settled into his comfortable chair on the bench – no hard wooden seat for him, as much time as he spent sitting on it.

Most people liked Judge Dieball. He could be informal if the situation arose, but never to the point of destroying the dignity of the proceedings; he could display compassion and consideration, and even a touch of humor once in a while. He glanced at the stack of papers on the desk and spoke up. “There’s not much on the docket this morning for once. I have received a request to move a case to the head of the docket due to the physical condition of the plaintiff, so there’s no point in making her endure the seating any more than necessary. So in the matter of the emancipation of Janice Lufkin – Miss Lufkin, are you present?”

Once again, Janice stood with Cody’s help. “I’m here,” she said, barely loud enough to be heard.

“Miss Lufkin, are you represented by an attorney?”

“Yes, sir,” she said. “Mr. Schindenwulfe.”

Dieball was actually thoroughly familiar with the whole situation, but a certain format had to be followed. He turned to the attorney and asked, “Mr. Schindenwulfe, please proceed.”

“Yes, your honor,” Schindenwulfe said. “Miss Lufkin has been an orphan since last week. She is seventeen years and five months of age, and a junior in high school. The John Archer family has offered to take her into their home and care for her until she recovers her health, and continue to care for her through high school. However, there are a number of issues, including the estates of her father and brother, which will be needed to be dealt with before she reaches her majority. Given the lack of any other known blood relatives, she is petitioning the court for her emancipation and authority to conduct her own affairs as an adult.”

“Miss Lufkin,” Dieball asked her directly. “Is this your wish?”

“Yes, sir,” she replied.

“Are there any relatives you know of who could take you in?”

“None that I know of,” she shook her head. “My . . . my father lost track of his brother a long time ago, and he was in prison at the time. He might still be, for all I know.”

“Mr. Archer,” Dieball said, addressing John, “am I correct in assuming that you and your wife are agreeable to having Miss Lufkin live with you until she’s through high school? You are willing to provide the support needed for her in that period?”

“Yes, your honor,” John replied.

“And are you willing to assist her with clearing up the affairs of her father’s estate?”

“Yes, your honor.”

“Then I see no reason to not grant the petition. Miss Lufkin, you are hereby emancipated from your status as a minor. Please understand that this is a limited form of adulthood. You will still be unable to register to vote until your eighteenth birthday, or to purchase alcohol until your twenty-first. You will find other restrictions. In addition, there are some protections that you enjoyed as a minor that no longer obtain. However, in most things you are now free to conduct your affairs as an adult, so please use your new powers wisely. There is some paperwork involved. When you leave the courtroom, you can check with the clerk of the court across the hallway for the certification you will need. Good luck to you, Miss Lufkin.”

“Thank you sir,” she said. “I appreciate it.”

“Thank you, your honor,” Schindenwulfe said, turning to show Janice and the Archers out of the courtroom.

In a few seconds they were out in the hallway. “Wow,” Cody said with a mild headshake. “That was easy.”

“Things usually are easy if you have your ducks in a row,” Schindenwulfe smiled. “Fortunately, they lined up pretty easily for once.”

“I don’t know about this,” he sighed. “I figured it might take all day.”

“It can happen,” the attorney nodded. “I could see ways that this could be dragged out until Janice is eighteen and the whole point would be moot. I don’t handle emancipations very often. In fact, this is only the second one I’ve done over the years. But we had the advantage of a clear cut case handled in a timely manner, and that can count for a lot.”

“Locked up tight,” Livingston said. “Cheap lock, it could be busted easily, but it might be noticed.”

“Yeah, that would be a little beside the point,” LaFayette agreed. They knew in small towns people sometimes don’t lock their doors, which made sneaking into a house easy, especially for people who knew what they’re doing, which he and Livingston did. However, the Archer family appeared to be an exception to the rule. “We got several good basement windows, though.”

“Yeah, let’s take a look,” Livingston agreed. Even people who were good about locking doors sometimes weren’t as good about locking windows, and for some reason basement windows were even less likely to be locked than ones at a higher level. What’s more, basement windows in older houses like this could often easily be unlatched even if locked – and the fact that it had been opened might not go noticed for a while, even years.

“We’d better be quick about it,” Abernathy said as Livingston headed off the back porch; he followed, along with LaFayette. He’d taken the precaution of putting on street clothes, rather than his uniform, mostly because Livingston had suggested it. “They might not be too long.”

“This shouldn’t take long,” Livingston said. “We’re just damn lucky you found out the whole bunch of them is going to be in court this morning.”

“Yeah, but there are only like four items on the docket and it’s Probate Court, so they could go quick,” Abernathy protested.

“So we don’t fucking waste time,” Livingston snorted. “All we’ve got to do is get in, find a logical place to hide the shit, look around a bit to get the lay of the land so we have a real reason to seek a warrant, and get the fuck out of here. It should only take a few minutes. We’ve done this before, we know how it goes.”

“Hey, that one looks like it ought to be pretty easy,” LaFayette piped up, pointing at a basement window next to the porch on the back side of the house.

“Good a choice as any,” the older drug cop agreed. “Back of the house, no view of the street, kind of out of the way. Let’s do it.”

“Got ya,” the younger cop said as he pulled a long, heavy flat-bladed screwdriver from under his coat. He knelt down in front of the window, strategically placed the blade near the latch, and gently pried down. Sure enough, the single-thickness window popped right open. “Got braces,” he reported. “But I can take care of that.” In no more than a moment, the window opened inward. He stuck his head inside and said, “Jesus, would you look at that?”

“Another meth lab?” Abernathy asked.

“No, the goddamnedest model railroad I ever saw. Shit, that thing is fucking huge! We’re gonna have to go in feet first, and watch our step so we don’t fuck up anything.”

“Fucking model railroad,” Livingston snorted. “Goddamn toy, but yeah, try not to break anything. Something like that, they’re going to know someone has been here.”

Many people with experience of living in small towns say that they don’t like it because everyone knows everyone else and knows everyone else’s business. Even Candice had referred to living in a small town as “living in a fishbowl.” It can be a major pain in the neck if you’re trying to keep your privacy. However, once in a while it works for you.

The basement window in the back of the Archer house may have been inconspicuous and screened from the street, but it was certainly not screened from Eleanor Casitas, the Archers’ backyard neighbor. Eleanor, a widow in her seventies, had long had the habit of sitting around the kitchen working on her coffee while she got her daily dose of Regis and Kelly. She happened to be up refilling her cup when she noticed the three men in the Archer’s back yard, looking like they were up to no good. She was watching when LaFayette popped the window, and by the time he was sliding inside, Eleanor was calling 911.

Emergency calls in Spearfish County are handled by an emergency call center staffed by the sheriff’s department, located with the department at the county jail. For the most part, the center was not a busy place. Mary Tingley, the dispatcher on duty, thought that she was bored more often than not in the dozen years she’d held the job. She was one of four people who rotated the duty, and most of the time she went through the whole shift and only got a handful of calls, many of them minor things. Still, a breaking and entering at nine in the morning seemed pretty unusual to her. “You’re sure it’s a break-in?” she asked Eleanor. “I mean, it’s not service people or something?”

“Why would they be using a pry bar to open a basement window with no one home?” Eleanor asked rhetorically.

“All right,” Mary conceded. “I’ll get some response coming.” She only had to move a couple inches to key the microphone for the joint county police frequency. “City units,” she called. “Active breaking and entering reported at 117 Grove Street.”

She sat and listened for a moment, but got no response, which when she thought about it wasn’t very surprising. She knew that Charlie Wexler was out of town, and that Fred Piwowar was probably asleep. She wasn’t sure if Bill Abernathy was back from his vacation yet, but if he wasn’t that meant that the department might not be covered – they just didn’t have the officers with one gone to cover twenty-four hours a day. “City units,” she called again, without adding the information about the breaking and entering. The sound of the call filled the empty building of the Spearfish Lake Police Department, but didn’t come out of Abernathy’s portable, which had been shut off and left on his desk.

It wasn’t much of a problem and Mary didn’t let it sit there for very long. The Sheriff’s Department and the city police had a long history of backing each other up, since operating shorthanded was normal for both departments. And, as luck would have it, 9:17 on a Monday morning was about the only time all week when the Spearfish County Sheriff’s Department wasn’t shorthanded. Rather than putting out another call, Mary got up, walked across the hall to the conference room, and broke in on the sheriff’s weekly staff meeting. “Active breaking and entering reported at 117 Grove,” she said without preamble. “No response from city units.”

“At this hour?” Sheriff Stoneslinger asked.

“That’s what the caller said. Eleanor Casitas on Oak Street, it’s across the back yard. Three men, no signs of any kind of service uniforms, and they broke a basement window to gain entry.”

“Jeez, that takes balls,” Stoneslinger said. “Might be the Wagner brothers. Sure would be nice to catch them red-handed for once. Let’s go get ’em. If it’s the Wagners, they may be armed, so let’s make damn sure we get the drop on them. No lights, no sirens.”

Mary stepped out of the way to allow the sheriff and nine deputies crowd out the door, some in uniform and some not. The Wagners were a major pain in the neck for law enforcement around the area, and if they were clients of the Department of Corrections again for a while things might be a bit quieter around the area. Plus, Mary was pretty sure that the Sheriff wouldn’t mind stealing an arrest right out from under Abernathy’s nose.

The Spearfish Lake Record-Herald had been the main newspaper, and most of the time the only newspaper in Spearfish County for over a hundred years. A weekly, it was a pretty small affair with only two reporters, one of whom was a part-timer who concentrated her reporting only on school sports. The other reporting position had been held for many years by a string of “junior reporters,” mostly fresh out of journalism school and looking for a line on a résumé before they moved on to other, better things in a year or so. While many of the junior reporters would never be heard from again, every now and then one or another of them wound up making some waves in the world of journalism. These included Andy Bairnsfether, who had reported on the White House for CNN for a number of years, and Brenda Hodunk, who had won an Aherns award at the Record-Herald and part of a Pulitzer elsewhere before moving on to World News Network. That meant any following Record-Herald junior reporter had some tough acts to follow, and they were expected to be competent and on the ball.

Luke Colby was currently the junior reporter – he’d been at the paper for about six months, had done what seemed to be an adequate job, and was sending out résumés and keeping an eye open for possible openings everywhere. Like a lot of junior reporters, he considered Spearfish Lake to be pretty far out in the sticks. He looked forward to the day when he could make it to a decent sized city where there might be something more important to cover, and a little more interesting life to live.

Part of the Monday routine for Luke was to make a call at the Sheriff’s department to get a look at the call log, arrest records and the like, since that made up a not insignificant part of page two of the paper. Usually, that was done about seven in the morning, but Luke was running late because his car wouldn’t start – damn the cold weather in this frozen wasteland, anyway – and he’d had to have someone come give him a jump. As it happened, he was sitting in the call center office when the breaking and entering call came in and saw the deputies heading out for the biggest response he’d ever seen in Spearfish Lake. He’d heard of the Wagner brothers – most junior reporters in the last ten years or so were quite familiar with the stories about them. It didn’t take much to realize that this big a response could be a story that would look real good in his clip file, and might even get him out of this godforsaken town. So he wasn’t very far behind the deputies as he ran to his car and followed them to the scene, hoping to get a few good photos on the digital camera he normally carried in his car with him.

Damn, he thought as he drove the few blocks to Grove Street. Gonna have a lot of cop stuff on the front page this week . . . and most of it with my byline. That’s gotta help get me out of here!

“Jesus,” LaFayette said, looking around the basement. “Would you look at all this shit? There have to be a million places here that you could hide something like a small stash. How much shit could you get into one of those little boxcars?”

“How the hell would you find it again if you hid it in one of them?” Livingston snorted. “We’d better not use a train car. Look for something else, something that isn’t going to move. I mean, shit, hide it like someone wanted to hide it. Abernathy, let’s you and me look around a little bit, see if we can find something that’ll give us cause to ask for a warrant.”

“Nothing real obvious,” the chief said. “But you’re right, you could hide a month’s output of the Lufkin’s meth lab down here and no one would think to look for it.”

“That’s what they make drug dogs for,” Livingston replied. “When we get the fucking warrant, we really need to remember to bring a dog with us. Christ knows what one would find.” He turned and walked away from the model toward the far end of the basement, to what looked like a workshop and office area. “Shit,” he said. “Look at all those bottles of glue and stuff. Shit, there’s enough model glue there to get half the school high. Maybe we could work something like that?”

“I don’t know,” Abernathy shrugged. “It’s all legal, after all, and with all that model stuff they have a legitimate excuse for having it.”

“Yeah, but it’s something,” Livingston shook his head. “Doesn’t always matter if it’s a legitimate use or not if they have it there. How about that gun safe? Shit, they could have a lot of shit in there, or guns or stuff.”

Abernathy went over to the gun safe. “Locked,” he said. “And that’s a pretty good lock.”

“I could probably tickle it given enough time,” the older cop replied. “Shit, that thing is big enough they could have a dozen AKs in there. God, when we get a warrant, it’s going to take a hell of a long time to tear everything apart.”

“I’d be a little careful about that. I don’t know how bad I’d want to pay for damages, and you busted up enough stuff when you came in.”

“Ah, we get the fucking warrant and nobody will care how much stuff we busted up, especially when we find the shit we’re planting down here.”

LaFayette was still looking for a good hiding place for the packet of meth that they’d gotten from their storeroom down in Camden. There were so many good places – how to find the right one? This wasn’t a bad house – he’d been in some real shitholes – but every time he thought he’d found the right place something else on the model caught his eye. He was still looking when he heard a board creak overhead, and then again. “Shit, someone’s here!” he said in a loud whisper to the two in the basement with him. “Let’s get out of here!” Without waiting for any more confirmation, he took off at a dead run for the window he’d come in. He scrambled up on the table not caring that he was knocking model stuff this way and that, and hoisted himself up through the window.

He was about halfway out the window when he heard someone yell, “Freeze!” He looked up to see four deputies looking back at him, guns drawn. Two of them had riot guns at their shoulders.

“Hey!” he yelled back, thinking quickly. “Police! Take it easy, will ya?”

“That remains to be seen,” Spearfish County Deputy Chris Aaronsen said, not lowering his riot gun at all. “Now come out slowly, keep your hands in the open, and don’t try anything or you’re just going to get blown all full of holes.”

“Shit!” Livingston whispered. “What the fuck?”

“Up the stairs,” Abernathy suggested. It’s the only way.”

For whatever reason, neither of them had heard the creak of the loose floorboards overhead, so it seemed like a pretty good idea – and the only possible way to clear the scene. Moving as quickly as they could, they headed up the stairs. Abernathy was hoping against hope that it was the Archers coming back – if it was, there was a possibility that they could bullshit their way out of things. With at least a slight attempt at stealth, he opened the door quietly, and tried to sneak through it. He was into the room, with Livingston right behind him, when he heard Sheriff Stoneslinger say quietly, “Hands in the air, you two.”

“But Steve,” Abernathy protested, looking at the sheriff, who was holding a riot gun leveled in his direction. “You know me.”

“Yeah, I do,” the sheriff said. “And that makes me want to ask what the fuck you were doing breaking into this place.”

“It’s part of an investigation,” Livingston said in a huff.

“Now, that’s interesting,” Stoneslinger smiled. “I hope you have a warrant.”

“Well, uh . . . ” Abernathy said.

“We’re supposed to be getting it,” Livingston protested.

“All right, let’s get this straight,” Stoneslinger said. “What the fuck were you doing breaking in here without a warrant?”

“It’s a drug task force investigation,” Livingston replied. “It’s not your jurisdiction.”

“Maybe not,” Stoneslinger smiled. “But breaking and entering is my jurisdiction, and that’s what you people have done if you don’t have a warrant. Now, up against the wall, you’ve got to be searched.”

“But we’re police officers, you know that,” Abernathy said.

“Breaking and entering is a felony,” Stoneslinger grinned. “I have to assume you’re armed, and you know what that means in this state. You know, ‘one with a gun gets you two.’”