|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

“Well, I guess there’s not much point in staying here,” Dale Bunting said to the remaining scouts. “But since we’re here, let’s take a little break. Have some water, and get into the snacks a little. While we’re doing it, let’s redistribute some of the load from Mr. Blanchard’s canoe into the other canoes. I’ll just have to tow it behind my canoe and unloaded would make it lots easier.”

“All right,” Bill Shorthouse replied. Bill was the senior patrol leader, the oldest of the scouts at fifteen, and something of the natural spokesman of the group. “Mr. Bunting, do you think Bob is going to be all right?”

“I hope so,” Dale replied as neutrally as he could. Though no words had been exchanged, he’d had exactly the same fear that Jim did, and right at the moment he didn’t even want to say the word in front of these kids. He didn’t even want to think it, but all he could do right now was to try to be as positive as he could be. “He’s probably just got some kind of bug. A shot or something will probably clear it right up.”

“I sure hope so,” Shorthouse replied.

“I do, too,” Dale said, knowing that about the best he could do right now was to keep the kids busy and try to keep them from thinking too much or talking negatively about it. “But it’ll probably take a while to find out. Let’s get our stuff rearranged and get on into town.”

The hospital only had one gurney, and no emergency room attendants, of course. Fike rolled the gurney down the long ramp to the parking area in back, with the two doctors and two nurses following along. “Morning, Garth,” Dr. Brege said to the banker. “What do we have here?”

“I got flagged down on the way into town by a bunch of scouts on a canoe trip,” he replied. “They’ve got a sick kid, he’s in back.”

“I’m Jim Blanchard, the scoutmaster,” the man just getting out of the car said. “This boy has been getting progressively sicker the last couple of days. He’s been coughing, had muscle aches and a headache, and finally got to the point where he couldn’t hold a canoe paddle. He’s only semi-conscious, now. Fortunately we were able to flag Mr. Matson down and have him bring us here.”

Between Fike and Blanchard, they were able to get the boy out of the car and onto the gurney, which they rolled up into the admitting room, where they slid him onto the only examining table in the place. Dr. Brege took the lead in examining the boy, who was delirious and not much help in answering questions. However, a quick examination proved that he was indeed running a high fever, and his reflexes were mixed – fair in one arm, but nothing in the other. The boy could apparently feel the doctor moving the fingers of the affected arm, but couldn’t move them himself.

Both Dr. Luce and his wife looked on with increasing concern, but for the moment said nothing. This was starting to look more than a little familiar to both of them.

The boy wasn’t able to answer very many questions, and then only vaguely. “I gotta pee,” was about the most information Dr. Brege was able to get out of him beyond some vague yeses and noes that didn’t always answer the question he was asked.

“Have you noticed anything about him not being able to urinate?” Dr. Brege asked the scoutmaster.

“No, this is the first I’ve heard about it.”

That was enough for Dr. Luce. “Dr. Brege,” he said, skipping the use of the first name he’d started to use. “Have you had the Salk vaccine administered yet?”

“No,” the older doctor replied. “It hasn’t gotten here yet. Have you?”

“Yes, and so has Penny,” Luce replied. “I think it would be a good idea if you were to step aside and let me handle this.”

“You don’t think?”

“I don’t know what to think, Harold. All I can say is that I haven’t seen anything yet that would rule against it. “

“Are you familiar with poliomyelitis?”

“I worked in a polio ward at Baptist last fall,” Luce said. “That’s where I met Penny.”

“I worked in it up until about a month ago,” Penny informed him. “This is looking very familiar. Every symptom I’ve seen is indicative of paralytic polio.”

“Your patient, doctor,” Dr. Brege said formally. “I know I’m out of my depth in this.”

“All right, everybody,” Dr. Luce said in a tone of command. “Everybody, surgical masks, right now. Do not touch this boy without surgical gloves and a gown. Does anyone know if the hospital has any gamma globulin?”

“We have a few doses worth,” Denise, the head nurse replied.

“Break it out,” Dr. Luce ordered. “Everybody in this room gets a dose, starting with this boy, and right now. If there’s not enough to go around, Penny and I will be last on the list, and if at all possible no one else new should be in the same room with him.”

Dr. Brege rummaged around in a cabinet and produced masks, gowns and surgical gloves, while Denise went to get the hospital’s supply of gamma globulin. In only a minute or so, Dr. Luce and his wife started on a more thorough examination of the boy.

“Sir,” Dr. Luce said to the scoutmaster. “I didn’t get your name, but do you know if this child has been given the Salk vaccine?”

“No idea,” Blanchard replied. “They had a mass immunization a few weeks ago, and there was a story in the local paper that they ran short and didn’t get to everyone. I know I didn’t get it. I was out of town for my job at the time.”

“The full course is three shots, but the first is probably the most effective,” Dr. Luce replied. “Are any of the other boys in your group showing any symptoms like this?”

“Not that I’ve noticed.”

“Well, that’s something, anyway.” Dr. Luce checked a few more things. “His breathing is poor,” he announced. “But at least he’s still breathing.”

“Herman, is there any chance it could be meningitis or hepatitis?” Dr. Brege asked.

“Could be, but the chances are getting poorer every time I glance at him. There’s only one way to settle it. Let’s get set up to do a spinal tap. I hope we have the equipment to give him that.”

“Yes, we do, but we haven’t used it in a while. I’ll get working on it,” the older doctor said.

“Doctor, let me handle it,” Denise offered, holding out a tray with a couple of small bottles, and an assortment of syringes. “I know where to find things. Why don’t you concentrate on giving everyone the gamma globulin instead.”

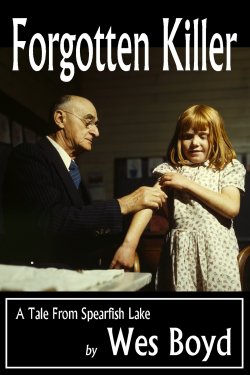

“Good idea,” Dr. Brege agreed. He pulled on surgical gloves, charged a syringe, and immediately gave a shot to the boy. Then, one by one he worked his way around the room, getting to everyone, including Garth, who was standing at the door and unable to tear himself away from the scene.

In a few minutes he was done. “Herman,” the doctor said. “We have about enough left for two more injections. Should I give them to you and your wife?”

“Let’s hold off for a few minutes,” Dr. Luce replied. “Penny and I did have the full course of the Salk vaccine, and it’s probably more effective, at least now that it’s had a chance to take hold. Let’s save these for now. We may find someone else who needs it more. Sir, uh, the scoutmaster, I didn’t get your name.”

“Jim Blanchard.”

“Mr. Blanchard, where are the rest of the boys on your trip?”

“As far as I know, still canoeing out on the lake. I told them to paddle into town and I’d meet them here. I don’t think they can be here in much less than three or four hours.”

“I would think it wise if we can give them all gamma globulin injections, too. Mr. uh, Fike is it? Can you see what you can do about getting some more of it here as soon as possible?”

“All I can do is call around and see if I can borrow some. The best bet is Camden General.”

“The sooner the better,” Dr. Luce replied, and turned back to his examination of the boy.

It took couple more minutes to get the boy set up for the procedure, which involves a long and evil-looking needle that was just about sure to scare the pants off of anyone who sees it. About the only good thing that could be said was that the boy wasn’t very aware of what was happening. They got him on his side, bent into a fetal position. Dr. Brege and Penny had to hold his arms and legs while Dr. Luce inserted the needle into his spine between the vertebrae as gently as possible.

Even as out of it as the Rathburn boy was, he was clearly hurt by the needle. In only a few seconds Dr. Luce had extracted a few cubic centimeters of spinal canal fluid, and removed the needle, causing him to visibly relax in spite of his now being rather unresponsive. Even to Garth, still standing near the door, it appeared the kid was sinking fast.

As soon as Dr. Luce had his sample, he turned and went into the lab adjacent to the admitting room. Denise had already gotten the microscope set up, and had a slide ready to be prepared. Luce squeezed a drop of spinal fluid onto the slide, then put it under the lens of the microscope – an old but apparently a good one. He had to fiddle with the focus for a moment, but once he got it clear, he let out a low whistle. “That,” he said under his breath, “is not good.”

“What?” Dr. Brege asked. He’d followed Dr. Luce into the room.

“White blood cells, lots of them. Penny, take a look please. You know what you’re looking for better than I do.”

Dr. Luce stepped out of the way, and his wife took his place. It only took her a glance before she said, “That settles that, all right. I’ve seen it before, but hardly ever that bad. Dr. Brege, take a look, please.”

Dr. Brege moved over to the microscope. “I’ve never seen anything that bad,” he said after a moment. “And I saw some really bad stuff during the war. What do you make of it?”

“Either spinal or bulbospinal paralytic poliomyelitis, one or the other, most likely the second, considering the rapid degradation of his breathing,” Dr. Luce replied. “Anything else would be a long shot.”

“How bad is it?”

“When it gets this far, it’s never good. I hate to say it, but my guess is that the boy is going to have to be in an iron lung within twelve hours, possibly less. I don’t see any hope of stopping it short of that, and an iron lung may not be enough, anyway.”

“That’s one thing we don’t have here,” Dr. Brege replied. “The nearest one I know of is in Camden. I guess the only thing we can do is to call down there and see if we can get this kid into it.”

Heidi Toivo was getting a little more concerned about her four-year-old daughter, Betsy. She was running a fever, and said her head hurt. What’s more, she wasn’t moving very well; she said her arms and legs hurt, but it was hard to get much more detail than that. It was getting pretty clear that she needed to see a doctor.

But there was a problem with that: the family only had one vehicle, a pickup truck that Hekki used for everything. He was gone with it right now; he said he had to pick up some things in town, and then he was going to stop off at Karl Langenderfer’s to do some welding on the tines of his cultipacker. He probably wouldn’t be home until lunch, at the earliest, and he could easily be longer if he ran into some trouble with the welding.

What was more, there was no telephone; the phone company hadn’t run lines out this far from town yet, although it had been promised in a year or two. Heidi had given some thought to just going out and walking the about three and a half miles to the Langenderfer’s where there was a phone – but that would take time, and the kids were much too young to be left by themselves, especially with Betsy sick.

After giving it some thought, Heidi decided there was only one thing she could do, and it might even help: she went out and started a fire in the sauna. At least it would be better to do it now, before it got to be as hot in the afternoon as she expected it to be. As soon as the heat built up a little, she went back into the house, took off her clothes and Betsy’s, and carried her out to the little wooden sauna behind the house.

Maybe it would help Betsy feel better. And maybe, Hekki wouldn’t be too long getting back.

The two doctors and Dr. Luce’s wife walked into Fike’s office. “Well, good news on one thing,” Fike said when he saw them. “Camden General said they can let us have twenty doses of gamma globulin, but no more than that. I’ve already sent Lloyd to get it; he ought to be back in a couple hours. They’ve got two polio patients down there, one of them in the iron lung. The other one ought to be in one, but they think they can hold out with him for a while.”

“Nuts,” Dr. Luce said. “That boy we’ve got out back is going to need to be in one as soon as possible. He can hold out for a few hours, maybe, but from what you say, it isn’t even worth calling Camden back.”

“They didn’t say that, but I could tell that’s what they meant,” Fike replied. “If anything, they sounded a little desperate themselves.”

“Well, that’s out,” Dr. Brege said. “Any other options? I know St. Mark’s in Marquette has a couple of them. They’re farther away, but any old port in a storm, I guess.”

“It’s not worth calling there, either,” Fike shook his head. “I talked to the administrator up there a few days ago. They have two, all right, but long-term patients occupy them both. One has been in one of the units for nine months and there’s no hope of her getting out of it anytime soon. The other is just about as bad, but hasn’t been in it as long. They’re looking for another unit, just in case we get a major polio outbreak this summer.”

“That puts us in a bind,” Dr. Luce said flatly. “That boy out back . . . well, he has maybe a chance in a hundred of being able to make it until this time tomorrow without some help with his respiration. Any other possibilities?”

“I don’t know,” Fike sighed. “The next closest possibilities are going to be farther away. Minneapolis-St. Paul, Madison, Milwaukee, then Chicago, and there’s no telling if anyone is going to have one free. If they don’t have one available in Chicago . . . ” He let the statement go; anything farther was probably out of reach.

“The only thing to do is get calling, I guess,” Dr. Luce said. “One of those is about the only chance the boy has.”

“That’s going to be tough, too, Dr. Luce,” Fike replied. “Since you’re new here, you may not know it, but the long distance phone service out of here is lousy. We can usually get a call as far as Camden without too much trouble, but it gets worse after that. If we try to call as far as, oh, Chicago, the call usually gets lost somewhere along the way. You can waste hours trying to get a call through that far. When a message has to get through, we usually use Western Union. They’re pretty reliable, and quicker in the long run.”

“Then we’ll just have to do it that way,” Dr. Luce said. “Let’s make up a telegram and send it to every large hospital we can think of within oh, three hundred miles, asking if they have an iron lung free.” He grabbed a sheet of paper off the administrator’s desk and wrote, HAVE MALE AGE 13 DIAGNOSED WITH BULBOSPINAL POLIO, NEEDS IRON LUNG QUICKLY. IF YOU CAN ADMIT HIM, PLEASE ADVISE BY WIRE AS SOON AS POSSIBLE. “Get that out to anyone you can think of and include our return cable address. Oh, and include the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, I don’t know what their cable address is. They might be able to help, too.”

In a few minutes they’d come up with a list of a dozen possibilities, and Fike was calling the Western Union office. “Here’s hoping,” Dr. Luce said. “That’s about the only chance the boy has.”

“You’d know better than I would,” Dr. Brege said. “I’m sorry, Herman.”

“Sorry about what?”

“Sorry that your very first case in Spearfish Lake is a bad case of polio. It’s too bad it couldn’t have been sniffles or a broken arm or something.”

“It would have been nice,” Dr. Luce shook his head. “I guess in this business we have to play the hand we’re dealt. I guess I’d better get back and see if there’s anything I can do for that boy.”

In addition to being a fanatic vegetarian, Garth’s wife Helga was death on smoking, too. That didn’t mean Garth had given it up, but he didn’t get to do it very often, and then only when he figured she wouldn’t catch him at it.

Right about then he needed a cigarette more than he had in years. Unfortunately, if there was anyone in the admitting room who smoked, they were busy with the boy. There wasn’t much that Garth thought he could do to help the kid, but there was someone else there with him who definitely needed some help: the scoutmaster, Jim Blanchard, who looked on helplessly, his face a study in sorrow. He needed some support almost as badly as the kid, and right at the moment helping him was about all that Garth could think of that he could do, too.

“Come on, Jim,” he said quietly. “Let’s go outside and get a breath of fresh air.”

“I . . . I shouldn’t leave him,” the scoutmaster protested.

“Jim, you need a little breather,” Garth said flatly. “You were in the war, weren’t you?”

“Yeah, in Italy, in the infantry.”

“I was there, too,” Garth told him. “You’re beginning to get what we used to call ‘the thousand-yard stare.’ Jim, you need to get away from this, if only to pull yourself together.”

“Yeah, I guess you’re right,” Jim sighed.

“I know it’s tough,” Garth said. “Come on, we need to talk.”

Jim reluctantly followed Garth outside onto what had been the porch of the old ‘cottage.’ “Darn it, I try to take care of these kids,” Jim said as soon as they were outside. “I have a responsibility to them, and now this has to happen.”

“Jim, I know exactly what you’re talking about,” Garth told him. “I commanded an artillery battalion in Italy. It was a National Guard battalion, and many of the men in it were from right here in Spearfish Lake. I felt I had a responsibility to do my best to bring them home safely.” He let out a sigh, and went on. “I didn’t always do that. I tried to do my best for them, but they didn’t all make it, so believe me, Jim, I know probably better than anyone else in town just exactly what you’re going through.”

“I just feel so sorry for the kid,” Jim replied sadly; Garth didn’t have to look to know that there were tears in his eyes. “How can I tell his parents he has polio? On a trip I led? I don’t know how I can tell them.”

“You’ll tell them because you have to, and you respect the kid and his parents. Look, Jim. The son of one of my best friends from school died under my command. His Jeep got hit by an 88 round and there was hardly enough left of him to put in a body bag. There wasn’t anything anyone could have done about it except not fight the war in the first place. I had to wait over a year to apologize to his parents in person for not bringing their only son home with me. But I told them because I respected them and I respected his memory. It doesn’t matter if you’re commanding a scout troop or an artillery battalion. You have to do what you can to take care of those you command.”

“I, well, I guess you’re right. I had a squad for a while, but that was about all, but it’s kind of the same thing, isn’t it?”

“It’s very much the same thing, Jim. Now, pull yourself together. You’re probably not done going through this tough time, but you’re going to have to face up to it. Just pull through and do what you can to help. I don’t know much about polio, but from what little I know the battle isn’t over yet. In fact, you may have gotten a little lucky. Dr. Luce is brand new in town. I haven’t even been introduced to him yet, but it sounds to me like he knows what he’s doing with that stuff. And most of all, don’t forget that you’ve got some other boys you’re responsible for, too.”

“Yeah, cripe. I’ll just have to do what I have to do. I just don’t know what it is, right now.”

“I don’t know either, Jim. I’ll help you out all I can. Just bear up under what you have to do, and let the crying go until you’ve done all you can do and then some.”