|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

The weather report and the view out of the window of the Stinson were right: there were thunderstorms building up, and there was a line of them right in front of Phil Gravengood as he pressed on toward Cedar Rapids. From what he could see it wasn’t a full out squall line, just isolated storms, but he knew better than to take them head on.

Reasoning that he’d rather be caught under a thunderstorm than be caught on top of one, he diverted his course to the left a little bit and let down in altitude. It was gray and dark down lower, and he knew he was pushing things a little, but a delay now would probably mean he wouldn’t be able to get the gamma globulin to Spearfish Lake before tomorrow. He still had some daylight left, so from down below he picked out an area with a few lighter spots and tried to head toward them.

It wasn’t a fun flight. It was rougher than the proverbial cob at times, but fortunately the tough stuff didn’t last too long, and after a while things cleared off. He knew he was left of course, so he altered to the right a little trying to follow the line of storms into Cedar Rapids, and soon he was able to figure out from his chart where he was.

He was relieved to be on the ground at Cedar Rapids – relieved in more ways than one; he stopped the Stinson at the fuel pumps and raced for the rest room. Several minutes later he felt much better. An airport attendant helped him fuel the plane, and in a few minutes he was back in the air again.

During his brief stop on the ground, he’d gotten his chart back on the horizontal stabilizer and laid a new pencil line direct from Cedar Rapids to Camden, a little to the right of his outbound course. The sun was getting low in the west now, and soon would be setting, although there would still be the long summer twilight.

Jim Blanchard was no less worried when Ron Shorthouse drove down Central Avenue and past the hospital. A cold chill went up Jim’s spine when he saw the place – the people there had done their best for Bob, but it hadn’t been good enough. He couldn’t get the vision out of his mind of the boy laying there on the examining table as the doctor took a spinal tap, and the dismay he’d felt when the doctor had said the dread word ‘polio.’

More than once on this sad trip up to Spearfish Lake Jim had remembered what he’d told the kids before the trip had even started: this would be a trip they’d remember for a lifetime. His words had come true, but in the worst possible way. And, it was especially true for Bob, what life he’d had left to him.

They had to stop at a gas station to find out how to get to Point Drive, but it proved easy to find. The sun was getting low in the west over the lake as they found Garth Matson’s house – it was a big place, right out on the lake shore. Ron pulled into the driveway to park, and the rest of the convoy pulled in behind him, or parked out on the street.

Matson came out to greet him. “Jim, I don’t know how I can tell you how sorry I am about the boy,” he said. “I haven’t said anything to the kids, not even that you were coming. Dale has them all out on the other side of the house.”

“Thanks, Garth,” he replied. “You have no idea how much I hate doing this, but I guess it has to be done. And thanks for everything you’ve done for us.”

Right about then Garth knew he’d just as soon be somewhere else – anywhere else. But he walked side by side with Blanchard around the house, the other parents following along behind.

It turned out the boys were on the beach, just getting set to build an evening campfire; Dale had them playing some sort of a word game just to keep them occupied. Jim didn’t say anything until he walked right up to the boys.

Bill Shorthouse was the first to notice him. “Mr. Blanchard,” he said. “What’s happened with Bob?”

Jim took a deep breath as the boys all fell silent. “I hate to have to tell you that Bob is dead,” he said finally. “He died early this morning. They were able to get him into an iron lung down at the university hospital in Madison, but it wasn’t enough.”

“Mr. Blanchard,” one of the boys said. “You’re kidding. Aren’t you?”

“I sure wish I was. The people at the hospitals, the man who flew us down there, they all did their best for Bob, but I guess the disease was just too strong.”

There was a stunned silence around the group. Garth thought he could see tears on some of the boys’ faces. They were too young to have to be confronted with the death of a friend – but then, Garth thought, is anyone ever old enough for that? He’d lost some friends in the war, good friends at that, but this was not the same thing.

“Mr. Blanchard, what happens to our canoe trip?” another one of the boys asked.

“I’m afraid it ends here,” Jim said. “If for no more reason than Bob’s funeral is going to be in a couple of days, and I think you all ought to plan on being there out of respect to him. I’ve talked it over with your parents, and we all agree that considering how much you’ve been exposed to polio it would be unwise to continue, whether you’ve had the vaccine or not. We wouldn’t want to be way out on the river somewhere and have another one of you come down with it. It was bad enough as it was with Bob, but at least we were close to the hospital here.”

“All right, Mr. Blanchard,” Bill said. “You’re right. I don’t know about any of the others but my heart wouldn’t be in it if we pressed on and missed Bob’s funeral.”

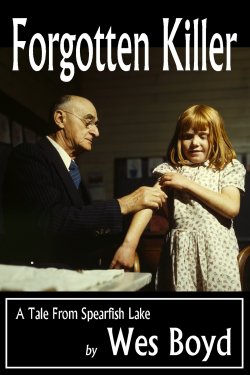

“I know you probably haven’t heard this,” Garth said. “But Dr. Luce checked all the boys over, and they’ve all had gamma globulin shots to increase their resistance. But still, I think it probably would be a good idea if you didn’t continue on, either.”

“After the funeral, could we maybe come back up here and pick up where we left off?”

“That’s not a bad idea, but it’s not something that can be decided now,” Jim said. “There are people here to take all of us home, and room for our gear. Mr. Matson, we can car-top some of the canoes home, but we can’t take all of them. Can we leave some of them here? If we don’t continue the trip in the next few days, we can come up sometime and get the rest of them.”

“Sure you can,” he replied. “Some of your gear, too, if you need to. You know how to contact me and I’ll be willing to help you out however I can.”

“You’ve done a great deal for us, Mr. Matson, and we have to thank you for it. Now, scouts, I think we better have a little prayer, and then be thinking about getting on our way. The folks who didn’t come with us are anxious to have you home.”

The boys – and the adults, and Garth – all joined hands for a brief prayer by Blanchard. “Guys, I’m sorry the trip had to end this way,” he said as it was finished. “I promised you a trip you’d remember for a lifetime, but I didn’t mean it like this.”

Not long after the sun set, the boys, their leaders and their parents had packed up and left, with only two canoes left leaning up against Garth’s garage. Yes, it was a shame it had to end this way for them, he thought, but it probably was for the best that they give up the trip. Still, he could taste their disappointment. It didn’t get easier to lose a friend as you got older, he thought.

Herman and Penny Luce were taking a break while Denise watched over the patients upstairs – now four of them. Another one, this one an eight-year-old boy, had arrived along in the middle of the afternoon. He wasn’t quite as sick when he came in, but had a fever and a stiff neck, two early signs of the disease. Herman had checked him over carefully and determined that he did have the disease, but perhaps not as bad. Still, there was no way of telling an outcome until the virus had run its course.

The two most recent cases, and the decision to use the gamma globulin heavily on the little Saunders girl, had cut into the remaining supply. The hospital had gotten a telegram from Kansas City in the late afternoon that the new supply had been picked up and was on the way back, so the shortage might only be for another few hours.

Dr. Luce was aware of the fact that gamma globulin wasn’t a miracle cure for polio. The best it could do was to reduce the damage done to some patients, and to give some protection to some people who had been exposed to it. That was a miracle in itself; any kind of a weapon in his hands was better than having none at all.

He and Penny had been busy all day; neither had had a chance to eat since the breakfasts Garth had brought to them in the morning. Now, as the sun was getting low in the sky, Denise had her husband stop off at the A&W to bring them takeout hamburgers – it was better than nothing since the hospital kitchen was closed – and in fact, hadn’t been open at all this day. While Denise looked after the patients, Dr. Luce and his wife took a minute to get off their feet and eat their meal – enjoying it was something beyond hope.

“Herman,” Penny said as she chewed on a none-too-warm hamburger, “this is going to go on for days. I don’t see how we’re going to be able to keep it up.”

“We’re just going to have to,” he said. “I’m used to long days from being a resident and an intern at Baptist.”

“Yes, and I remember you being asleep on your feet, too,” she replied. “Look, it’s down to the two of us and Denise. There’s only one more nurse available, and from what Denise tells me she’s pretty shy about wanting work with infectious patients. Denise says she has small children, so I don’t blame her in the slightest.

“I can’t, either,” Herman shook his head. “I would have thought she would have gone on shift by now, but we haven’t seen her. If she’s scared of working with infectious patients, it’s probably best if she doesn’t do it at all.”

“That’s my thinking, too. I think we should just take over one of the patient rooms downstairs and try to get some sleep here. Denise and I can trade off, and then call you when we need you.”

“That would work, at least for tonight.”

“It’ll get us through the night, but this could go on for weeks. Herman, the thing that concerns me is that we should be looking toward the rehabilitation of these patients, as well as just supporting them. You know, hot packs on the limbs, exercising the joints even if they can’t help with it, or are even not aware of it. But as far as I know even Denise doesn’t know much about that. Oh, she’s heard the techniques exist, but she’d never had to use them. But if we get a continuing flood of patients, it’s just going to get worse.”

“I don’t disagree. If we have double the number of patients, and I wouldn’t be surprised if we did by this time tomorrow, it’s going to push the three of us to just support them. I agree that we need to do more or we’re going to have people who are unnecessarily crippled. The only thing I can think of is to get some help. Putting hot packs on limbs and exercising joints is not something we actually need a registered nurse to do.”

“Herman, do you think we should look for volunteers from the community?”

“I can’t think of much else we can do,” he replied. “Who knows, perhaps there are some retired nurses who might be willing to help out in an emergency. Or just caring people. Granted, we’ll have to train them to protect themselves from infection and load them up with gamma globulin once it gets here, but it may be the only choice we have.”

“Herman, it’s not a bad idea, but how do you plan on finding these people?”

“I don’t know,” he shrugged, “but I do have one idea, and that’s to ask that woman from the local March of Dimes chapter this morning. What was her name? I’m too tired to bring it up right now.”

“Donna Clark, I think.”

“She’d be the first person I’d ask. She strikes me as the kind of person it’s hard to say no to.”

It was fully dark now, and not as easy to navigate, but Phil had a good idea of what his compass course had to be and occasionally he was able to pick out a town that seemed to indicate that he was on course. He was sure of it when a larger city began to show up in the distance. From perhaps twenty miles away he was able to pick out the green and white rotating beacon of the airport.

It had been a long day, with a lot of time in the air, so he was glad to be back in familiar territory at Camden. The fixed base operation was normally closed at this hour, but he happened to notice a car sitting on the ramp in front of the place, and the lights were on. He knew someone was supposed to meet him there so the gamma globulin could get the rest of the way to Spearfish Lake on the ground. With no lights at the home airport, he couldn’t land there until morning.

He pulled up close to the car and stopped the engine. As soon as the prop windmilled to a stop he was out of the door – he’d been getting a little stiff from sitting in the pilot’s seat most of the day.

“Are you Phil Gravengood?” the guy on the ramp called.

“Yeah,” Phil replied.

“I’m Roger Ebbett, from Camden General Hospital,” the man said. “I’m supposed to pick up two hundred units of gamma globulin from you and tell you to get on up to Spearfish Lake.”

“They don’t have lights at the airport there,” Phil protested.

“All I know is they told me to tell you to get on up there, they’ve taken care of the airport for you.”

“Well, all right, if you say so,” he replied, thinking that he had more than enough fuel to get to Spearfish Lake, and even make it back to Camden with lots to spare if it turned out that the airport wasn’t lighted after all. “You’re going to have to help me get the stuff out of the coolers; I don’t know how it’s packed inside.”

It turned out that the gamma globulin was in packages of little bottles, apparently fifty units to a package. Ebbett took four packages. “Boy, am I glad to see this stuff,” he said. “We’re almost out. When we heard you were making this special trip we knew we had to hop on it.”

“I’m glad we could help,” Phil said. “I guess I’d better get moving on up to Spearfish Lake.”

“Thanks for helping,” Ebbett said as Phil got back into the Stinson.

A few minutes later Phil was back in the air, down lower this time. Even at night the route to Spearfish Lake was familiar, although he couldn’t pick out many of the usual landmarks.

For most of the trip Phil had kept the Stinson’s radio on the Unicom frequency, 122.8, used at uncontrolled fields, and from habit he had it on now. Perhaps fifteen or twenty miles out of Spearfish Lake, he heard his call sign on the radio. “Stinson one four king from Spearfish Lake.”

That was strange, he thought. As far as he knew the only other aviation band radio in Spearfish Lake was the one in the Cub. What was this?

“Stinson one four king from Spearfish Lake,” he heard again, and realized it was Nick Farmer calling, one of his sometimes flight students, a guy who had been in D Battery with him in the first days of the war.

One way to find out. “Spearfish Lake, one four king, go ahead.”

“Come on in,” he heard Farmer say. “The runway is lighted. Winds negligible, altimeter two niner seven two, or pretty close to that.”

“Uh, roger that, Spearfish Lake,” he replied. How could the runway be lighted? That didn’t make sense!

He was coming up on Spearfish Lake now, with the town off to the right as he approached the airport, the unbroken blackness of the lake showing beyond almost as well as if it was lit. But his attention was ahead of him, where the airport should be – and there were two rows of tiny orange lights!

He had no idea how that could have happened but he was glad to see it. They really must want this gamma globulin stuff there. Using the faint lights for guidance, he lined up on the runway and started to set up his landing.

As he got closer, he realized that the lights weren’t a steady glow like a light bulb, but flickering a bit and not the right color, either. Right at the moment, that didn’t matter – lights were lights, and he could land by these. He could see he was getting close to the ground, so he started his flare, aiming for a three-point landing, and soon the Stinson was on the ground.

It was only when he turned the plane around to taxi back up toward the hangar that he realized what the lights were: highway flare pots, the kind he was used to seeing along the road to mark obstructions or construction sites! Someone had been using their heads on that one!

As he got a little closer to the ramp, he could see the hangar doors were open, and that the Cub had been rolled out onto the ramp. There were several people clustered around it.

Phil ran the Stinson up close to the ramp and cut the engine, noticing people coming out to greet him. “Wow,” he said. “You guys must want this stuff bad.”

“They’re down to one dose left at the hospital,” he heard Pat Burling say – he was a deputy sheriff, and Phil had been in D Battery with him in the first days of the war. “They’ve been saving it for a real emergency, and there must be at least twenty people waiting to get some of this stuff. They want you to take two hundred units on up to Marquette as soon as you can get it there. Someone from St. Marks will meet you.”

“Sure, can do,” Phil replied. “I just need to top off the tanks first.”

Less than five minutes later Pat was off to the hospital, with the light on top of his car flashing and siren going. “Wow,” Phil commented to Nick. “I guess they are anxious.”

“They’ve had three cases come in since you left,” Nick said. “Colonel Matson asked the road commission to send these guys out to set out the flare pots.”

“Good thinking. I’ll have to thank him when I see him.”

“Let’s roll this thing over to the pumps and get it topped off,” Nick told him. “They aren’t a whole lot less anxious for the stuff in Marquette. The flare pots are supposed to be good for all night, but I’ll stay here until you get back, just in case.”

“Nick, that’s a good thought, but I ought to be all right.”

“Probably,” Nick conceded, “but we’ve got trouble, and I feel like there’s something I ought to be able to do to help. This at least helps a little.”

Over at Brent Clark’s garage the work on the emergency respirator was going well – the plywood box was done; it even had plywood doors in the side so someone could reach inside and tend to a patient, along with glass panels so they could see what they were doing. The doors were held shut by furniture latches and sealed with gaskets made from the tractor inner tube Brent had brought back from the farm supply store.

The mechanical part wasn’t going so well. It was coming along, but some welding was needed, and every time they needed to do some, Joe had to take the parts over to his shop, and then return with them.

Finally, it got close to midnight. “Brent,” Joe said. “I think Dan and I need to knock it off for tonight. We’re beat, and we’re making stupid mistakes. What would you say if we were to quit now and get back on it in the morning?”

“I guess,” Brent said reluctantly. “As far as I know they don’t need it right away. I mean, if they did, we’d be getting some really frantic phone calls. Garth only told me that they wanted to have it available if someone needed it, so maybe nobody does.”

“I’ll tell you what,” Dan said as he put down his tools. “I’m sure this will work when we get it finished. It’s really pretty simple. But I sure hope that no one needs to use it.”