|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

The rest of Saturday was very long at Sanborn Memorial Hospital. The patient arriving in the early afternoon was followed only a couple of hours later by a second patient, both of whom were tested as having polio, but not sinking terribly quickly. Still, no one thought that was the end of the crisis, and things were expected to get worse before they got better.

Even after the arrival of the second Popular Mechanics unit, after some discussion, Dr. Luce decided to leave Gail Saunders in Ryan’s little respirator, at least partly because she was small enough to fit in it. If someone needed the second big unit in a hurry, it would be free. The new one was taken to an otherwise unused room upstairs in the hospital, plugged in, and tested; it would be ready to go at a moment’s notice, but it hadn’t had a patient in it by the time Garth decided it was time to go home and get some sleep.

It was after dark when Garth got back to his house. He was tired; he’d been going all day on a couple of cold hamburgers and several cups of coffee. It was much too late to go out to a restaurant; everything was closed by now, and he didn’t have the energy to do much more than open a can of beans, which suited him just fine. He wished he could call out to the club and see how Helga and the kids were doing, but it was too late for that even if there had been a phone at the club, which there wasn’t.

No news in this case, he reasoned, was good news.

After a tough day, he really needed to unwind a little, and that he could manage. While Helga may have been a vegetarian, she was no prohibitionist, and there were several bottles of very good German beers and wines in the refrigerator and on the shelf. Garth settled for a bottle of Engelbrau from the refrigerator; it was cold, it tasted good, and had just enough alcohol to relax him.

He was just trying to make up his mind about having another beer or going to bed when Phil came in. Phil had been staying with him for the last couple of days, but other than a few minutes when the scouts had been there the night before they’d hardly seen each other. “So,” Phil asked. “How was your day?”

“Long,” Garth replied. “I don’t think I’ve had a longer or tougher day since the war. Let me tell you, those people at the hospital earn their pay, and there were several of us there working for free.”

“Is that where you were?”

“Yeah, mostly putting hot packs on kids in pain and hurting them more by exercising their muscles to keep them from getting too stiff. You have no idea how hard it is to do that even though you know hurting them a little bit now is best for the kid in the long run. I’ll tell you what, when this siege is over with I’m going to be very happy to go back to being a banker.”

“How many kids do you have over there now?”

“Seven, I think,” Garth said, then stopped to count them in his mind. “Yeah, seven. Two of them are in respirators, wooden iron lungs that Brent and some of his buddies threw together. There’s a third respirator waiting, but it wasn’t in use when I left. Maybe it’ll just sit there. I hope so. Let’s not talk about it. What have you been up to?”

“Not much. I changed the oil in the Stinson, and did some other things to it. It went a little over time when I went down to Kansas City yesterday.”

“Was it only yesterday? It seems like it must have been at least a month ago.”

“No, just yesterday. Was it worth it?”

“No doubt about it. Herman has enough gamma globulin that he can dump a lot of it onto a patient if he thinks they need it. He said just before I left that one of the kids may be alive only because of the gamma globulin and the fact he’s in one of the wooden lungs Brent and his buddies built. There’s no telling if he’s going to pull through, but it seems likely he wouldn’t have gotten this far if you hadn’t flown down there. So what’s the deal on going down to pick up the Salk vaccine Donna told me about?”

“I need to leave before daylight,” Phil replied. “After I got the news that I had to go into Midway to pick the guy up, I flew to Marquette and borrowed some crystals for the frequencies I need to land there. That’s what I was just doing, fiddling with the radio in the Stinson.”

“Are you going to need the runway lit to take off in the morning? It’s kind of late to call the road commission, but there are people I could lean on if I had to.”

“No, I think I can get away without it if you can help me out. I often had to fly in and out of strips at twilight back in the war, just by Jeep headlights and things like that. If you can park down at one end of the strip, and we can leave the company truck out there with the lights on, I think that’ll be all I’ll need to take off. Then you can put everything back up at the hangar so it won’t be in the way when I come back.”

“I guess I can,” Garth yawned. “I’m just going to set my alarm clock for real early.”

“I’ll set mine, too. Between us we both ought to be able to get up and going in time.”

Thus it was that in the very early hours of the morning Garth and Phil left the phone company truck up at the far end of the airstrip with the engine running. Garth took Phil back to the Stinson, and then drove back down to the end of the airstrip in the Buick. As soon as he turned around he could see the landing lights of the Stinson taxi out onto the runway, and then turn towards him as Phil took off on his third mission of mercy in the crisis. This one was going to be even more important than the others, and might even turn the tide.

In popular movie westerns, rescue came with the cavalry charging in with bugles blaring and horses’ hooves raising a cloud of dust to save the day. But rescue didn’t come to Spearfish Lake that day on horseback, and there was no sound of bugles – just a red, white and black 1948 Stinson Voyager appearing from out of the southern sky and doing a straight-in approach to land on the grass runway of the airport. Garth was waiting for the return of the Stinson, and as soon as it was up to the hangar, Phil and Doug Walters, a worker for the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, unloaded several cases into Garth’s Buick.

In a way, it was a shame that only Garth was there to greet them, for no cavalry in any western film could have been greeted with more relief than those aluminum chests containing thousands of doses of the Salk polio vaccine.

The vaccine was new. It had only been announced a little less than four months before, after tests of the vaccine carried out the previous year had shown it a good, though not perfect, protection against polio. The news had been greeted with a huge relief all across the country. Dr. Jonas Salk was rightly treated as a hero, a savior, a saint for lifting at least some of the fear of the dread disease. It had been a desperate struggle on the part of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis and several companies to get it made and distributed to where it was needed, especially where there were local polio outbreaks like the one in Spearfish Lake.

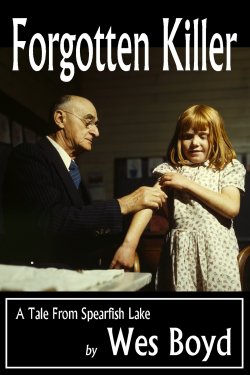

The first place Garth drove the Buick with its precious cargo was to Sanford Memorial Hospital, where the workers who had been fighting to save the lives of the infected children were inoculated with the vaccine. They, including Garth, had been the most at risk, after all, having been exposed to multiple sources of the contagion. Those first inoculations to be given didn’t take long, and soon Garth drove them on to the high school, where Donna Clark had set up a mass inoculation station in the hall of the bottom floor.

There was already a long line of people waiting. From the moment that Phil had wired from Midway Airport that he was about to start back with the vaccine, Carla Holstrum, “Central” at the phone company, had started passing the word to everyone in town. In those days of party lines, a long ring denoted emergencies. She rang every line and told everyone who picked up their phones that the Salk vaccine would be available at the high school in a matter of hours. She also asked everyone who answered to pass the word to neighbors who didn’t have phones, or who may not have gotten the message.

The message also got out in other ways. Attendance was sparse that morning at the Spearfish Lake First United Methodist Church. A good many people were scared to be out and around to places where they might be infected with the virus. When the church service got under way, Pastor Richard Upton stepped up to the pulpit and said, “I think we can best serve God and ourselves this morning not by sitting here, but by going over to the high school and getting inoculated against polio.” He walked down the center aisle of the church and out the door, with the whole congregation following him.

When the Methodists arrived at the high school they found much of the population of the town already there, and more coming by the moment. It really was a quiet crowd; there was no cheering, no exuberance, just a quiet feeling of profound relief. Children weren’t running around playing and yelling, just standing somberly with their parents as they waited patiently in line for their turns. There was little talking; people and families stood apart from each other in small groups, glad that the fear of the dread disease was being lifted at least a little bit.

There was some talking, quiet words mostly, about the children they all knew were up in beds in the hospital. They knew some of the children were in the wooden “iron” lungs that had been built the day before – all three of them in use now, with nine patients in various stages of the disease. Almost everyone knew the children, or at least their families; no one said it out loud, but everyone there was glad that it wasn’t someone from their own family. No one objected when people from the immediate families of those afflicted were routed right to the head of the line – they were clearly in more danger than anyone else.

The lines moved slowly, mostly because there were only so many people available to administer the vaccines, but they worked steadily. No one seemed to mind it moving slowly, and no one left the line, either.

Up at the head of the line, Dr. Brege interviewed everyone who came through, especially every family who came through, looking for symptoms that might indicate that someone already had the disease. He found five possibilities, and told them to go straight to the hospital as soon as they’d received the injection – which wouldn’t hurt and might help.

Two cases proved to be just routine sniffles after Dr. Luce had examined them more thoroughly, and one had polio, but a mild enough case that the patient could be sent home for observation. The final cases were admitted to the hospital; one developed into a mild paralysis, and the other was more serious – but both seemed to be limited by early and heavy doses of gamma globulin. It later turned out that one of the two only had to spend three nights in the hospital before being sent home.

Marilyn Householder and Beatrice Brege from Dr. Brege’s office worked hard at setting up and giving the inoculations, aided by Willie Halford and Doug Walters from the National Foundation. Once again, there was very little said, but the feeling of relief was heavy in the air once the shots had been administered, even though the four often had to warn people that it would be a few days before it took full effect. Everyone would also need two more injections in the near future to get the full protection offered by the vaccine. As soon as they had their shots, Donna Clark handed out shot cards to those who’d just had the injections, partly as a record, and partly to remind them that they needed further doses.

The table where Donna handed out the shot cards also had a bucket on it. On the bucket was a sign that read, “All March of Dimes donations will support local polio victims.” The bucket was soon filled, and replacement buckets, one after another were put in place, filled not just with dimes, but with any other pocket change, dollars, and other bills. It went without saying that those who had contracted the disease were going to be facing a long haul of recovery. Many felt that since the shots themselves were free, they ought to donate something to those who hadn’t been lucky enough to have them before they were infected.

The line wound around the school, and clear out to the football field. While it may have moved slowly, everyone who stood in line knew that they were a small part of a huge victory over an unseen killer.

Though he had played a large part in the fight against the disease in recent days, Garth Matson didn’t see much of the culmination of the effort, at least not for a couple of hours. As soon as he knew everything was moving smoothly, he went back home, took off all his clothes, and took a shower – a long and hot one, and with the strongest soap he could find. Once he had completed that, he put on clothing he hadn’t worn all week, then drove the Buick over to Brent Clark’s.

Brent wasn’t there, of course – he and Ursula and Ryan were standing in line over at the high school. But Garth had borrowed the keys to Ursula’s car, and now he left the Buick behind, got into her Chevy, and drove out to the club.

He was very leery about doing this step, but after his experience of the last few days, he was even more apprehensive about bypassing it. He parked the Chevy in front of his summer cottage, where he saw Helga laying out in the sun, while the kids, as usual, were playing on the beach. He walked up to Helga, staying a few feet away, of course. She looked up from the book she was reading and said, “Garth! Why are you here?”

“Are you all right?” he asked. “Are the kids all right?”

“Everybody fine is,” she replied. “How are you?”

“I’m still all right,” he said. “Is everybody all right here at the club?”

“As far as I know. Everything quiet has been.”

“Good. Get some clothes on, and get the kids dressed. I’m taking you all to town.”

“Garth, are you sure that’s wise?”

“There’s something that has to be done,” he said. “They’re giving out Salk vaccines at the high school, and I want you and the kids to have them.”

“Garth, no! The vaccines – can they not cause polio themselves?”

“Can’t happen. I talked with some people, and they don’t use a live virus, but a killed one. They can’t hurt anyone.”

“Garth, I do not want you to do this. I hear the vaccines can hurt, and I do not think it wise to take the children where there polio is.”

“That’s a small risk,” he said. “It is a risk, yes. But Helga, not having the vaccine is a lot worse risk. If you had seen some of the things I watched happen to small children in the last few days, you’d know what I mean. You haven’t seen a kid screaming with pain as a muscle spasm hits them. You haven’t seen a kid struggling to get enough of a breath to stay alive. You haven’t seen a kid showing up with a fever and a sore neck, and having to be in an emergency respirator within a couple hours, wondering if they’re going to live at all. I don’t want my kids going through that, Helga, and I don’t want you going through it. The kids are getting the vaccine, and that’s final.”

“But Garth, even so wise I don’t think it is.”

“You may not think it’s wise but I know better. The risk from taking the vaccine is very small, and the risk of not having it is huge. Helga, I know you have ideas that you believe in, and I know how firmly you hold to them, but thinking that getting the vaccine is bad for the kids is totally wrong. You don’t know how wrong you are. Now, are you going to get the kids dressed or do I have to?”

“Garth, you seem very much like you want to an argument about this have.”

“No argument about it. Helga, I mostly let you have your way, whether I think you’re right or wrong. In fact, I think you’re wrong a lot of the time, but many of them are on things where it doesn’t much matter. This does. Now, one more time. Get dressed and get the kids dressed, or I’ll do it. It’s that simple.”

“Garth . . . ”

“Kids!” he yelled. “Go get dressed. Now! You’re going to town with me.”

“Garth, we should talk about this first.”

“No, I’m done talking. Helga, there are times you have to listen to me and abandon some of those goofball ideas you got from your father. This is one of them. If you don’t want to get dressed and get the vaccine, fine. You don’t have to, but even at your age you’re taking a huge risk. But Helga, after what I’ve seen, I won’t risk the kids, and that’s final.”

Carrie, the oldest of the kids and the natural leader, came running up. “Dad,” she said. “What is it?”

“Go get dressed and get the other kids dressed. You don’t have to get dressed up, but we all have to go to town.”

“OK, Dad. What’s this all about?”

“I’ll tell you in the car. This is not the time to stand around talking. Get everybody dressed, now.”

“OK, Dad. Rod, April, hurry up,” she called to one of her brothers and her sister. “We have to get clothes on. Dad is taking us to town.” She hurried off, herding the rest of them toward the house, leaving Garth and Helga alone.

“Garth, I cannot let you this do,” she replied. “It is not good for the children.”

“Helga, the kids are getting the shots, and that’s final. If you don’t like it, fine. I’ve been through one divorce, and I can go through another one if I need to, but I don’t intend to see one of my kids in a polio ward. I know what it’s like and it’s no place for any child. Now, you can make an idiot of yourself, or you can go get dressed too. I’m not going to put up with any more garbage about this from you.”

“Garth . . . ”

“Which way is it going to be, Helga? The kids are going to get the vaccine whether you like it or not, and I’ll do it the hard way if I have to.”

“All right, Garth,” she finally conceded. “I still think wrong you are. But you are being so firm about this I cannot fight it.”

“Like I said, Helga, if you’d seen what I’ve seen the past few days, you’d know just how right I am.”

Helga was not in a very good mood as Garth drove Ursula’s Chevy toward town. She had a hard head and didn’t give in easily; Garth usually let her have her way – but not this time, with potential lives at stake. There were times when he really had to put his foot down, whether she liked it or not.

“Dad,” Carrie asked as they drove out the gate. “Where are we going, and why are we in Mrs. Clark’s car?”

“You’re going to get the Salk vaccine,” he explained. “There’s polio in the area and I’ve been working with kids sick with it. I don’t want you to get it, and things are that simple. As to why we’re in Mrs. Clark’s car, I used my car to take a kid to town the other day, and he later died of polio. I don’t know if any of the germs or viruses are still in my car, but I’m not about to take the risk of having you kids in it, either.”

“There’s polio in town, Dad? Are there kids sick?”

“You’re in class with Tommy Perkins, right?”

“Yeah, he’s kind of neat.”

“He’s in an iron lung right now. That’s the only way he can breathe, and he’s real, real sick. The last I heard he was still alive, but they’re not sure he’s going to make it.”

“Tommy? Wow! Are you sure?”

“I helped put him in the machine. It wasn’t fun and not a pretty sight, Carrie.”

“Dad, are we going to be safe from polio when we get these shots?”

“Not all the way safe, but a lot safer after you get them. I still want you kids to stay out at the club with your mom until this eases up. With polio, there’s no reason to run any more risk than you have to. Unfortunately, I’m still at risk after picking up that kid the other day.”

“Then I guess I’m glad we’re going to get those shots.”

“I am too, honey. I’m just glad they’re there to get.”

Helga was still sullen as she stood in the long line to get the shot, but Garth counted it as a victory that she was there at all. The kids were going through with it no matter what she thought. At least she didn’t make a scene when Dr. Brege asked her and the kids a few quick questions about running a fever or having sore muscles – after all summer in the sun nobody could even report a sunburn. But she bared her arm for the shot, and Garth didn’t even stare her down to do it. She was even nice to Donna when she was handed a shot card.

Garth knew it usually wasn’t worth the effort of getting in a fight with his wife, but this time it had been. He felt a little lighter in his heart late in the day when he drove back out to the club. It would be a while before he’d dare spend much time with his kids, but the chances were now much greater that it wouldn’t be in a polio ward.