This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

I’ve heard a lot of people say that the fifties were dull and drab with nothing much going on, while the sixties and the seventies were the wonder years. As far as I’m concerned they’re full of crap. In my book the fifties, especially the early fifties, were a golden age, a time when everything was possible, and it seemed like it would never go away; the sixties and the seventies were dull as hell.

Life was good back in those days. Of course, when we’re talking about any "old days," life is always good, but looking back from this distance it was particularly nice. It was before the Interstates, so when you went anywhere it took you longer, since the main roads ran slowly through every little town. But since we were going slower, there were always interesting things to see along the way, and you got a chance to see them, rather than just looking at the blur of farm fields while trying to keep from getting run over by the passing semis.

It was before the days of fast food chains, so when you stopped for something to eat everything was always a little different; there was a sense of adventure when stopping at a strange roadhouse. It was before Lady Bird Johnson went to war against the billboards, so there was a lot of individuality along the road. People talk with nostalgia about things like "Burma-Shave" signs; we really had them, and some of them were pretty good. Yes, there were billboards all over the place, at least on the main roads. Some of them were pretty ugly, but they gave you something to look at as you were driving.

Most of all, it was back before television really took hold. People didn’t just settle down in front of the box and tune out the world; they made their own entertainment and were a part of things. They went out, and went out as families. Although gas was fifteen cents a gallon, the average annual income was around $3,000, so often people didn’t go far. It was a treat, a special occasion, to go out to a ball game, or to a movie, or to the races.

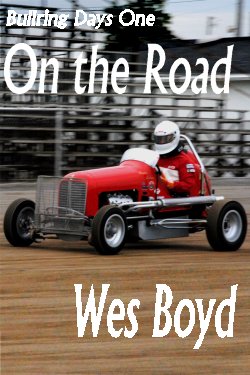

Yes, especially to the races. I won’t say that every small town had its own little dirt track speedway, but there were a lot of them around. Add to that horse tracks just about everywhere, even baseball fields or hay pastures were among the places that you could hear a small Offy or a V8-60 in a midget, or a larger Offy and other bigger engines in sprints and modifieds, not to mention stock cars of every description.

In the big places like Chicago you could watch racing every night of the week. Admission was twenty-five or fifty cents, hot dogs and pop were a dime each. You could take your girl and have a really fun date on a couple of bucks. Rock and roll came in during this period, and one of the songs that sticks in everybody’s memory is Hank Williams’ Hey, Good Lookin’, where a punk talks about taking his girl out in his hot rod Ford with a two-dollar bill. It might have been the races that they were going to.

In some places there was racing once a week, or sometimes once a month. In others, it was a big event when the Midwest Midget Sportsman Association came to town; it might only happen once a year, or not even that often. Then, that little local horse track or ball diamond or cow pasture would become a place of magic, with engines roaring, flying dust, spins and wrecks, thrills and chills – things that would go a long way toward perking up the normal day-to-day dullness. For one afternoon or evening there would be excitement, something to look forward to, something to remember – some were times to remember for a lifetime.

The next morning, the racers would be gone somewhere, over the hill, the next town, a town a hundred miles away, someplace else that seemed magical just because it was someplace else. They still had steam engines on a lot of the trains in those days, and the steam whistle called to you in a way that diesel air horns never did, calling to your desire to see what was down the tracks.

The racers knew what was there, here and there and everywhere else – another dusty track, another small town that had people who wanted to know what elsewhere was like, another set of crummy tourist cabins – and sometimes, not all that often, another small-town girl with dreams of romance and adventure.

It was a hard life – dusty, dangerous, and primitive, with no place to call your own, meals eaten on the fly, never enough money. We lived damn rough, but most of us were veterans and we knew how to live rough since we’d done it for a while. Some of us were children of the Depression like I was, and we’d never really known anything but rough, so things like having a job, having fun, and seeing the world made it seem like we had it pretty soft, too.

I wouldn’t have traded it for the world, and I wouldn’t trade the memories for the world, either.

I first met Frank Blixter on Okinawa, back in the spring of 1945 while the battle was still going on.

Back in those days the government would draft you right out of high school if the local draft board had a quota to meet. I guess that in the spring of 1944 the Fremont County draft board must have been scraping the bottom of the barrel because my name popped out of it. I was a senior in high school then, and to tell the truth I was looking forward to graduating and then getting in the service – it seemed to me that the adventure of a lifetime was out there and it was passing me by. In many ways I was right – for many of us, maybe even most of us, World War II was the adventure of a lifetime. As far as we could tell the war wasn’t going to last a whole lot longer – maybe a year or two, if that, and a lot of us wanted to be a part of it. We didn’t really hear all that much about the war, just a little bit on the radio, which my folks and I listened to most nights, from Life magazine, which we didn’t get at home but I read at school sometimes, and the newsreel when we went to town for a movie maybe once a month.

When my draft notice came, I knew from the local paper that I could get a deferment that would last me until I graduated, but I didn’t want to wait. Since I knew that the school would go ahead and graduate me with the class anyway, I went ahead and reported. Neither Mom or Dad were too crazy about the idea, but with that draft notice in my hand there wasn’t much they could say about it. For me, getting out of Fremont County, Nebraska was about as big a deal as going to war. Like a lot of kids in small towns, I wanted out. I wanted the music, the fun, the money, the adventure of living in a city, and I don’t mean Omaha, either.

Now, my dad had been through World War I, and he told me one thing: try to stay out of the infantry; they live like dogs and die like them, too. I figured that was pretty good advice, as if I’d have much to say about it. As it turned out the Army decided to make a Jeep mechanic out of me, and then sent me to the Army Air Corps, which sent me to a base in western Kansas, which was a lot like home although even flatter and with fewer trees.

I mostly worked on Jeeps throughout the winter of ’44 and ’45. It gets cold out there on the high plains, and there were times I sure wished that I was warmer, and I felt I’d like to be a little closer to the war.

Along in the early spring of ’45 a levy came down, gathering troops to go on to another place, they didn’t say where. By that time I figured that just about anything was better than Kansas, and the war looked to be getting over with, so when my name came down I was just as glad.

They put us on a troop train up at North Platte heading for the west coast. By this time in the war they didn’t have enough regular passenger cars to go around, so they put us on what they called a troop sleeper, which was just an old boxcar with some hard bunks built roughly into it. I felt just a little like a hobo as I rode that old boxcar westward, up through the Rockies and across the Great Basin desert, then over Donner Pass and down the Sierras to San Francisco.

We were taken right to a troop ship and marched on board. That wasn’t a lot of fun; we were crammed in there six high and about all we could do was stay in our bunks or wait in the chow lines which wound all around the ship and took hours to work your way through. We were about a week getting to Hawaii, where they landed us. I didn’t see any hula girls or anything else but another ugly Army camp for the few days I was there, and before long I was on another troop ship, part of a replacement detachment heading on west.

Of course we all knew that the battle on Okinawa was going on by now and that there had been lots of casualties, so I figured the Army was about to forget that I was a Jeep mechanic and give me a rifle. Most of us in the detachment figured that, some people looked forward to it and some didn’t.

We had to anchor offshore for two or three days before they finally sent us ashore and stuck us in another thrown-together tent city. You could hear the big guns shooting in the distance but that was about all. I wasn’t there for more than a day or so when they called my name at a formation, and I had to grab my stuff and get on a deuce and a half to ride to yet another place.

It turned out I’d been half right – I was back in the Army, in an infantry division, but I was assigned to the division motor pool as a Jeep mechanic. It seemed like for once the Army had managed to put a square peg in a square hole.

Of the group I had been with I was the only one assigned to the motor pool. The headquarters first sergeant had a runner take me over there, and that was where I met Master Sergeant Frank Blixter.

"Son, with them corporal’s stripes you don’t look like you come in the Army last week," he snorted. "You know anything about fixing Jeeps?"

"That’s mostly what I’ve been doing for the past year," I told him.

He asked me a couple simple questions about how you work on Jeeps, and I guess I answered them all right when he said, "You’ll do, son. You ever done any car racing?"

I told him the truth, that I’d never even seen a car race; they weren’t very common in Fremont County, Nebraska.

"Never?" he asked. "They didn’t have racing where you were?"

"I guess there’s a track down in Omaha," I told him truthfully, "But I’ve only been to Omaha twice and once was on a troop train."

"Oh, well, can’t have everything, I guess. Look son, you do good work and I’ll overlook the fact that you don’t know nothing about race cars."

I should probably explain that I didn’t much mind him calling me "son" since that was what he called just about everybody any younger than he was, at least back in those days. He was in his early thirties then, and he was just darn near old enough to be my dad, anyway.

For the benefit of the younger folks reading this, I probably also ought to explain that the draft in World War II was a whole lot different than people remember from Vietnam. The big difference was that they didn’t just draft eighteen year olds, they drafted everybody from eighteen to thirty-five, so a unit wasn’t just kids, it had a range of ages and some more mature people to help keep things in line, and for the most part it worked pretty well.

There was an officer in charge of the section, a Lieutenant Frawley. I never really got to know him because we hardly ever saw him; it may have been just as well because what he knew about Army motor pools could have been written on a bottle cap. I don’t want to say he was a pain in the ass or anything like that, it was just that he’d been wounded in combat and was trying to hang on and be useful, which I thought was a good thing. He spent an awful lot of time in the hospital and more around the division headquarters doing this or that, I guess. It actually worked out pretty well because that left Frank in charge of the section most of the time, and Frank did know what he was doing.

Since this was an infantry division, we didn’t have a whole lot of vehicles. Some were in pretty good shape, but some had had the crap beaten out of them on half a dozen islands in the Pacific, most that you never heard of before or since. In the first part of my time there I was pretty busy; the battle was still going on, and there was always something that had to get done yesterday. We were supposed to work twelve hours a day, but we mostly worked when there was light enough to see – they wouldn’t let us work under lights for fear of snipers shooting at us, and we didn’t have any way we could black out a work area. Cleaning up, getting some chow and getting some sleep took up most of the rest of the time.

It seemed to me that the section was understaffed, and it turned out that it was. I soon found out that in the early days of the battle a couple artillery rounds landed right in the middle of the vehicle park where there weren’t any slit trenches nearby. Five or six guys had been killed and a number shipped home with wounds. Most of the section had been together since they left the states back in ’42. I heard stories about a lot of places like Guadalcanal and New Guinea, and I never quite got straight where and when most of them were. I was the new guy, not part of the crowd that had gone through all that stuff, and there were times that it was no fun to be an outsider.

On the other hand, these guys weren’t quite as close as a combat unit and there had been transfers in and out, so the old-timers were actually in a minority by then – and Frank set the tone for the section, anyway. He was a good guy; he liked his fun, but his attitude was that he wanted to kick the crap out of the Japs so he could get back to the states and fire up the race cars he had stuck in a barn someplace.

After the battle was over there was kind of a letdown. One rumor going around was that we were going to get shipped back to Hawaii for a rest period, but another rumor was that the division was going to be the first wave of a beachhead against Japan. That seemed pretty likely to us at the time, and I’ve since learned that it was dead true, but it never happened that way, thank God. I really hadn’t been directly affected, but everybody knew that taking Okinawa had been a damn mess and no one figured that landing in Japan was going to be any easier.

In any case, we weren’t quite as busy as we had been, not that it made things any easier, because for a while there wasn’t much to do on duty and a damn sight less to do off duty. About once a week there’d be a movie up at the division headquarters and just about everyone went to see it. There was never any beer, even any Cokes, just water and occasionally a little powdered lemonade. There wasn’t much to do but to write letters home and wait for the occasional letter back, and after a while it got pretty damn boring.

I heard it said later that a busy soldier is a happy soldier, while a bored soldier is one looking for trouble and will manage to find it. One of the old-timers in the motor pool, a private by the name of Antonelli, was from Chicago. He’d grown up in a family that had run an alky cooker back in the Capone days, and Antonelli knew a thing or two about making hooch. I have no idea how he did it or what he used to make it with, but he threw together a potent brew. He kept it for him and his buddies, which was just as well, because he had a batch go bad on him one time. Nobody died but a couple guys came close. Antonelli wound up getting sent to the stockade and a couple guys got sent to the states; the rest of the crowd was scattered to line companies.

Now we were really shorthanded, and we were back to being fairly busy. Along about that time, Lieutenant Frawley got hold of me one day and said, "Austin, Sergeant Blixter tells me that you’re a pretty good mechanic."

"I like to think so, sir," I replied respectfully.

"Do you drink, Austin?"

"No, sir." That didn’t mean that I wouldn’t, given the chance. We’d never had anything to drink at home – my folks were that kind of people – and I was still under twenty-one so couldn’t drink much in the states. And other than something like Antonelli’s hooch or the occasional bottle of 3.2 beer that made it to the troops, there was nothing to drink.

"Good. We’re going to be getting some new people in here, and it’s likely that none of them are trained mechanics. You’re a sergeant now; you’ll have to help keep things going."

Sure enough, in the next day or two we got some people in, mostly guys from line companies. Some of them were real duds, but others had been hurt enough to keep them out of the lines but not bad enough to be sent home, and a couple of them had some idea of what they were doing, so we got along. One of the latter was a corporal by the name of Spud McElroy. I found out later that his name was really Sylvester, but you didn’t dare call him that or he might hurt you. It didn’t take long for me to find out that he was a real mechanic and knew what he was doing, and it didn’t take Frank long to find out that Spud was a racer who had run sprint cars and midgets along the east coast for several years.

At that time we lived in a camp of wall tents not far from the motor pool. We were off at one side of the tent city, with other headquarters company units in other parts of the camp. Like I said, there never was a lot to do, but for lack of anything better to do people would get together and just shoot the shit. There were usually six of us to a tent, sometimes more, but right then we were thinned out. Spud wound up in my tent, and the only other guy there was a corporal by the name of Gerald Wollett, who we usually called "Carnie."

Now, Carnie was a character. Like me, he wasn’t an old-timer, but he’d been around the outfit longer than I had. We called him "Carnie" since that’s what he was – he’d grown up around carnivals. His dad owned rides, and he grew up mostly living out of the back of a truck or in a tiny little travel trailer, setting up rides, running them and tearing them down. He had a million stories, mostly about some really off-the-wall people. He knew a lot of the show tricks, too, and sometimes did one or another of them. Carnie was only so-so as a mechanic, but had other talents that made him valuable. Mostly, if we needed something, Carnie knew how to get it. I don’t want to say he was light-fingered, but he wasn’t above lifting something if he had to. His real gift was talking; I swear he could talk a nun out of her panties without even half trying.

By this time I’d heard a lot of Carnie’s stories and didn’t always know what to believe or what not to, but I think we both figured that having this new guy in the tent was going to at least make for a few stories we hadn’t heard. That first night the three of us were sitting on the ground out in the shade in front of the tent, smoking cigarettes and shooting the bull when Sergeant Blixter showed up. The racing stories got going, and they were some good ones. Carnie and I just shut up and listened to them.

It was then that I started to learn about Frank Blixter, just sitting there and listen to him swapping tales with Spud McElroy. Frank wasn’t just bullshitting about racing, he was a car racer through and through. He built his first sprint car about the age of seventeen in 1929, mostly in his dad’s back yard on the outskirts of Detroit, a town called Livonia. It was more or less based on Model T parts he got from a nearby junkyard, and I seem to recall him saying once that he had ten or eleven dollars invested in it. He raced that car and wrecked it and rebuilt it time and again for the next few years, and actually managed to survive – it would be hard to call it making a living – as a professional race car driver in every bull ring he could find to race at in the Midwest. It was pretty hard, but everything was hard back in the Depression days. He trailered the race car behind another Model T he’d rebuilt from a couple of wrecks using junkyard parts, wore that car way out, then built a Model A pickup from a wreck and used that for a while.

Spud’s story was pretty much the same, but it was east coast and since he was younger he’d started a little later. He had an uncle who had a sprint car that he raced around, apparently not real seriously, and one evening he wrecked it and busted himself up pretty bad in the process. Spud wound up having to load the wreck on the trailer and haul it home. His uncle didn’t figure he’d be driving for the rest of the season, so Spud made a deal with him – if he could fix the car up, he could race it the rest of the year. Spud’s high school was out for the summer – this must have been about the summer of ’36 – and he got three or four of his buddies to help him. In a couple weeks they had it pretty well fixed up, even with a new if pretty ugly coat of paint. That first summer Spud only raced it a couple times a week, but he did pretty well with it, winning about a dozen heats and even a couple of mains, something his uncle had never managed. He also wound up a few bucks to the good on the deal, something else his uncle had never managed.

The story that Spud told was that his uncle wasn’t very happy about having his sister’s kid show him up like that, and the deal wasn’t going to continue for the next season. But by then the racing bug had bit Spud pretty bad, and he figured on building a car of his own, again with the help of his high school buddies. Spud started out with a Model B Ford that had been wrecked, but by the time they got done with it there wasn’t much left of the Model B but the inspiration. The thing looked really home-made, but it went pretty good the next summer, and Spud ran pretty well with it, winning a few races along the way. By then Spud was out of high school but winning more money racing than he could have had at working if there had been a job to be found, so he just sort of kept with it.

Along toward the end of the season, Spud ran across a guy that wanted to buy his car even though it was ugly as hell. He was willing to give him a good price, so Spud went and built another car that winter. His uncle still had been giving him hell, so Spud figured that to keep peace in the family he’d better not be in sprint cars, because his uncle wouldn’t like having him whip his butt even more than he’d already been doing. By then midgets were starting to get popular, and Spud figured that was the way to go.

Now, a midget in the thirties was a different animal from what they’ve become over the years. Back in those days the midgets were supposed to be cheap, something a guy could build in his garage and go racing. They really were pretty small, single seaters of course, only about four feet wide and seven or eight feet long. The engines were real small compared to the sprint cars, and in the early days it was a little tricky to find an engine small enough in size and displacement to be used in a midget. Especially in the early days you had guys running midgets with Elto outboard motor engines, and even some engines that originally came mounted on a washing machine. Spud’s first midget still had a rail frame, but some more serious parts, including a Ford V8-60 from a wrecked car.

Even the thought of a V8-60 gets my blood to flowing these days. The story that Frank told us back on Okinawa was that for whatever reason, Henry Ford hated six cylinder engines, mostly because Chevy had a six and got there first. Ford had come out with their V8 in 1932, and it was a good engine for cars as big as they were then. It was a flathead engine, so simple like Ford liked them, and it was robust and reliable. In a few years, though, it became clear that Ford needed a smaller engine for the economy buyers. Since old Henry wouldn’t let his people build a straight six, they came up with the idea of shrinking the V8. Frank said that, according to his dad who was a foreman at Ford, they just about had to start from scratch to build an engine that looked like a shrunken big V8, although there were a few parts that were compatible.

But the designers did it right. They wound up building this little V8, officially 60 horsepower, although it was no trick to hot it up to a hundred or more. In later years with lots of work and hot fuel some people got as much as 300 horsepower out of them, although usually not for long. But as far as Frank and Spud were concerned, the V8-60 was the perfect engine to go in a midget. Spud had one of the first on the east coast in a car that was considerably more advanced than his first ones – and Frank had just about first one in the Midwest.

Frank spent several years racing the sprinter he’d built from that old Model T. It was a work in progress all the time; Frank was forever changing or rebuilding something on the car. It may have had a Model T engine to start with, but not for long. By 1933 or so he was running a big flathead V-8 that had been warmed up quite a bit from stock, and there wasn’t much left of the original Model T. Along in the middle part of the thirties – it must have been 1936 again – the old race car got wrecked worse than normal. Frank felt it was just as well, since even with the newer engine the car had gotten to the point where it couldn’t keep up.

After giving the whole matter some thought, Frank approached a friend and sometimes sponsor he had in Livonia, a car dealer by the name of Herb Kralick. Herb had a small Ford agency, and he had the racing bug bad. He was especially fascinated with the new midgets that were coming out, and Frank knew that Herb wanted to race one – not have a driver do it for him, he wanted to do it himself.

The deal that Frank cooked up with Herb is that if Herb would give him the money for the parts and provide him with the space to work on it, he’d build a midget for Herb while he built his own big car. Herb had some space in his shop, so everything fit together.

The deal was that the midget was to be first class, not just built out of junk parts, and Frank put some effort into it while he was building his own sprinter. Frank never said just how much of the stuff he bought for the midget found its way into the big car, or how much help he managed to get from Herb’s mechanics. Herb wound up spending six or seven hundred dollars on the midget, which was a lot of money considering you could buy a new car for three hundred dollars. He got his money’s worth, though; the midget was really top of the line, and was fitted with a brand new V8-60, straight from the box but considerably souped up.

Come spring, they dragged both cars down to the nearest bull ring for a trial. Frank was reasonably satisfied with his sprinter, it would go a lot better than his old Model T-based thing, and he figured he could win some races with it. Then they got Herb’s car fired up. Frank ran it a few laps and figured it was all right, so he gave it to Herb to run.

"For as much as Herb knew about racing," Frank told us in front of that tent in Okinawa, the first time I was to hear the story that I heard many times over, "I don’t understand why he didn’t know how to power slide through the corners. He ran a few laps, just pussyfooting around, and then decided to get on it. Right there in turn one he overdid it. There was just a wire fence on the outside of the turn, and he went right through it sideways. I don’t know why the hell it never turned over, but he spun around several times and finally all I saw was a great big splash, with water flying everywhere. Herb came to a stop with the car sunk in a swamp with his head just sticking out of the water. It was spring, the water was cold as hell, and the frogs were making a hell of a racket. Well, I raced over there in the pickup, jumped into the water and got him out of the car. Well, I got him up on shore and asked, ‘Herb, you all right?’

"He said, ‘Hell no, I shit my pants when I hit that swamp. Are those things always that wild?’ I told him that they were, pretty much, you had to drive them or they’d drive you. ‘Fuck it,’ he said. ‘Would you give me fifty bucks for it where it sits?’ Well, I kind of figured something like that was going to happen, but I didn’t think it would happen that quick, so I figured that I’d better take him up on the deal before he thought better of it. And that’s how I got into midgets."

Frank fished it out, cleaned off the mud and the frogs, and fixed it back up. He did a little more horse-trading, and came out of it with a Ford truck that had a bed just big enough to haul the midget. After that Frank could pick and choose where he wanted to race a little more; he could race either the midget or the sprinter or both if it seemed like it was worth the trouble.

Frank raced the two cars for years, right up to the summer of 1940, when his luck ran out and he got number 158 in the draft lottery – which meant he was in the first batch picked. The Army was expanding like mad in those days; Frank knew how to work on stuff so he got promoted pretty quickly and had made master sergeant shortly before he landed on Okinawa.