This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Chapter 22

Iíd pretty well talked myself right back out of it by the time I got up to the house. It would be a heck of a reach and a lot of work to even consider it at all. It would take some breaks and good luck to make it work if it could be made to work at all, and it all just seemed like a little too much. I had my mind so made up I almost didnít mention it to Arlene.

But, I did, more as a conversation piece than anything else. Arlene has surprised me often over the course of my life, but I donít think she ever surprised me any more than she did when she said, "You know, Iíve been wondering about that. It seems such a shame to see it sitting there empty." In fact, I soon found myself pointing out what I thought were difficulties or drawbacks, and she was pointing out ways to overcome them.

To be honest, the idea grabbed her harder than it grabbed me. It wasnít long before we called up our current favorite babysitter, Lauri Pieplow, one of my history students, to come over and watch the kids for a while so we could go out and look it over. Half an hour later, Arlene and I were sitting in the pickup truck on the start-finish line, just looking the place over again, throwing ideas at each other. "This place is such an eyesore," I commented, "That itíd be tempting just to tear everything down and start over."

"Itís not the best looking place Iíve ever seen," she agreed. "But, you know, you could really improve the looks of the place by just tearing that fence down. Iíve never been thrilled with it in the first place."

"Yeah, I suppose," I told her. "Thatís one of those things thatís always bothered me about the place. It seems kind of walled in for all the land thatís here. If we were to rip out the fence, at least in the corners and replace it with a woven wire fence farther back, thereíd be plenty of room for a runoff area. Thatíd save having to fix it all the time when a car went through it, and might keep some cars from getting bent up, too."

"I remember racing in places with walls like that," she said. "They always made me a little nervous. A runoff area sounds like a good idea, like that one they have at Maple Shade. I wonder why they have a board fence around the track here at all."

"Probably because that was the way things were done when they built this place," I shrugged. "It pretty well means that you had to buy a ticket if you wanted to see a race."

"Well, I suppose thatís true," she agreed. "But you about have to have a fence to keep people off the track. That doesnít mean that it has to be an ugly wood thing with peeling paint like that. I suppose your woven wire fence could be farther back; thatíd help with the crowd problem."

"You know," I replied after thinking about it for a moment. "Just getting this thing going again, I donít think weíre exactly going to have a crowd problem. Back when Rod suggested this, I got to thinking that until we get a good show going we wouldnít lift enough tickets to pay for someone to take them."

"Why bother with tickets at all?" she said. "At least until we can get it going. Youíre right. At fifty cents a ticket, we might be lucky to make twenty bucks. Why donít we just run it for the racers?"

"That might not be a bad idea," I told her. "I recall Smoky saying one time that he made a lot more money out of the back gate from entry fees and pit passes than he took in from the front gate. If you didnít worry about the gate, thatíd take care of the need to put much effort into repairing the bleachers."

I glanced up at the bleachers, which werenít in good shape overall. "That might have some potential," I said. "If you just tore down half the bleachers, you might find enough good stuff to go a long way toward fixing the other half."

We sat in there in the pickup tossing ideas back and forth. Each of us had spent an awful lot of time at race tracks and other places back in the days of the MMSA, and some since. Along the way both of us had picked up a few ideas about things that we liked, and things we didnít. "Itís a darn shame we donít have the money to pave it," Arlene said. "I like racing on dirt as much as the next person, but darn it, itís dirty. You get track dirt into everything, and if youíre in the stands and the wind is wrong youíre going to end up as dirty as the racers. I always wondered why people wanted to put up with it in the first place."

"Well, thereís no money to pave it this year, for sure," I told her. "But that might be something weíd want to consider in the future if we can get that far. But everything depends on being able to draw racers, and Iím not sure how to do that. People who are into it usually have their Friday and Saturday night places all picked out. Weíd have to draw from some of them, and what reason would they have to come here? We canít afford anything much for payouts, after all. There might be a few locals that this would be less of a tow for, but the few left around here who were racing after Smoky and Glenn ran them off are probably established elsewhere."

"I donít know," she replied. "How about if we raced Sunday afternoon? There donít seem to be a lot of tracks around that do that."

"Not that I know of," I agreed. "And I donít know why that is. I donít think itís a blue-law thing. I thought about that idea, too. Iíd have to check, but I donít think thereís anything here that would prevent us from racing on Sunday. It might draw some interest we wouldnít get otherwise."

"Maybe itís because some racers think they need to have a day of rest, a day with their families," she replied. "I donít know what we could do to make this more family friendly, but there ought to be something. You know, thatís one thing that always bothered me about that fence on the back stretch, it kind of sealed off the pits from what was happening on the track. How about if we were to just leave a single section of bleachers on this side of the track, and move part of them over to the back stretch so the people in the pits could get a better view? If we started getting crowds again we could always rebuild the front stretch bleachers."

"Itíd take time, and worse, itíd take money," I told her. "You realize that most of whatever we do is going to come down to you and me, donít you?"

"Itís going to take more than just the two of us for a lot of things," she said. "But we might get some help here and there. The money is an issue, but we might be able to exchange time for money here and there."

"Money is still the issue," I told her. "Weíve got some good ideas, but weíre going to have to work out the money issue, and how weíre going to get people racing here."

"You want my gut answer on that?" she smiled. "I think that once the word gets around that weíre trying to bring this place back to life that weíll have enough interest to get going. Weíll just have to go on from there."

Arlene and I sat there for quite a while going over ideas, and between us we were able to come up with some good ones, some of which we might even be able to do. By the time we headed back to the house to relieve Lauri, I think itís safe to say that both of us had been provisionally talked into the idea.

The kids spent the rest of the day in front of the TV or otherwise raising hell like kids do, while Arlene and I sat in the kitchen of our old farmhouse and went through a lot of paper, trying to make the numbers come out. Realistically, the property at that price was a deal. It was undervalued even as farmland and that number didnít include improvements to the place that might be salvageable. One of those improvements was the track itself Ė it had been a track for a long time and the dirt was well packed from years of racing and grading. Carving a dirt track out of a piece of reasonable ground is one thing, but it takes time and care to make it a durable racing surface, but once you have that it doesnít go away easily.

After a lot of fiddling and diddling Ė all by hand since this was before the days of electronic calculators Ė it pretty well became clear that it was out of our reach, which had been my gut feeling from the beginning. Arlene and I decided that we could handle the purchase price, even though it was steep for our budgets, and we would probably not lose money if we were to plant everything to beans Ė but again, that had been my gut feeling from the beginning. But even the cheapest improvements were going to cost money we didnít have, and there were operational expenses that were little more than guesswork at that point.

"Letís face it," I told Arlene finally. "Weíre going to have to come up with some money somewhere if weíre going to make this work. Iím willing to go to the bank to talk about the land, thatís one thing, since land is land and we can always plant beans if thatís what it comes to. But to make the improvements and run the place as a track, I donít want a bank involved since theyíre going to want their money back sooner or later, preferably sooner. Weíre probably not talking about a lot of money, but it has to be money that might be a while being paid back since itíd have to depend on the price of soybeans."

"We could run it past Dad or Willy," she said. "Dad might be willing to kick in a little. Willy, hard to say, since heís got so much money tied up in his rail."

"Maybe there might be a few others," I said. "You know, a couple hundred here, a couple hundred there. Craig might be interested, for example."

"Well, yeah," she said. "But itíd be nice if we could limit the number of hands in the pot." She frowned, shook her head, then suggested, "How about Frank?"

Iíd be a liar if Iíd said that the idea hadnít crossed my mind. I remembered sitting around some bar somewhere with Frank and Spud a decade and a half before, when Frank said that heíd never have been able to make it in racing if he hadnít had the connection to Herb Kralick. Herb was such a racing nut that he could be talked into almost any damn fool thing involving racing, and the existence of the MMSA proved it. Frank was a much more accomplished racer and had made a few bucks here and there over the years, but I had the impression that he wasnít going to be as soft a touch as Herb had been. "I wouldnít be surprised if heíd kick in," I replied. "Covering the whole nut, thatís a different story, and I wouldnít want to guess. But I think heíd be about the first person weíd want to talk to."

It was late in the day by this time, much too late to head to Livonia, but I wanted some time to sleep on this idea anyway. Maybe it wouldnít seem like such a great idea in the morning. Besides, I wanted to talk to a few other people, not committing myself to anything, but just to get a feeling of how a resurrection of the Bradford Speedway would go with some of the local racers I knew, as well as a few other people around the community.

For example, I did some checking and found that there was no law or zoning out there in the township that would prevent Sunday racing, although there were bound to be some preachers who would bitch about it. I got a chance to talk with Craig and Beth about it, and they agreed that it would be nice to have a local kart track, even if it involved racing on dirt, and Craig agreed to ask around the karting community about it. A few days later, he got back to me and said that heíd heard quite a bit of favorable comment if the entry fees could be kept to reasonable for families with several kids.

A lot of the kids who had been Junior Stock racers back in í61 and í62 were gone now Ė Don Boies was dead by that time Ė but there were a couple left around who were still in racing. They agreed that theyíd be willing to come out on the odd Sunday afternoon to get a little more racing in. One of them, Eric Hosler, commented that there were still some Junior Stock cars from that era sitting around unused since those days, and there might be people interested in running some of them. I didnít get a lot of commitment to the idea, but then I didnít ask many people, either Ė but I asked enough to know that there was some interest there. Whatís more, the interest ran more than one way Ė I got several offers of "Hey, if you do it, let me know. Maybe I can help you out getting the place cleaned up or something." I figured that most of those offers would evaporate like dew under a summer sun when the time came, but at least I got the feeling that people werenít opposed to the idea of getting that eyesore on the edge of town cleaned up.

In the meantime, Arlene and I worked on our figures, trying to work out how we would spend money if we managed to find it in the first place. Iíd never heard the term "business plan" before, but that was essentially what Arlene and I were putting together Ė an outline of needs, priorities, and the like with dollar signs attached, along with ways we could save money and get along with fewer people to run the place.

We spent a lot of time kicking those kinds of thing around, and in the process came up with what I thought was a radical idea. The place had a bigger front parking lot than was needed, and in the past there had been some money spent to spread some gravel around, so the place didnít turn to mud like the back parking lot and pits did. What we came up with was the idea of abandoning the back lot, at least temporarily, and using the front lot for the pits. It would take a little re-arranging, though not much, and it would allow us to have a single concession stand rather than the two they had in the past. It would simplify the bleacher issue. It simplified other issues, too; we wouldnít charge for a pit pass, but just for a simple entry fee. The entry fees and concessions would have to cover our income until we got to the point where we could start to charge for the front gate. This meant that everything had to be done on a shoestring, but when youíre doing things on a shoestring you sometimes find innovative ways to tie the ends together.

By the end of the week, we had it boiled down on paper as much as we could. Now it was time to roll the dice.

I managed to get an appointment to see Frank on Saturday afternoon, up in Livonia. We agreed to meet at his house, and it proved that he and Vivian had a nice one, not that it was any surprise. We sat and relived the old days for a while before he said, "Mel, I know weíve just been talking around what you came up here to see me about. What do you have in mind?"

"Long story," I said. "You remember the Bradford Speedway, where I got hurt that time?"

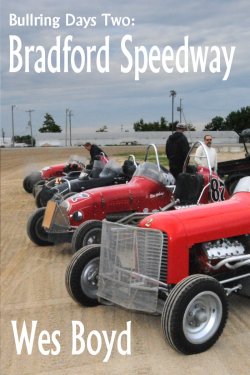

"Oh, yeah," he said. "Not real well, but I think we did three or four dates there over the years. It was kind of a dump, as I recall it."

"If you thought it was a dump in the early fifties, you should see it now," I said, handing him some photos Iíd taken earlier in the week Ė theyíd just come in to the drugstore that morning. "Itís been sitting abandoned and empty for years, and itís in foreclosure. The bank has been after me to take it over and get it going again."

"How much do they need for the place?" he asked.

"A little over five thousand," I told him. "Iím just half tempted to buy the place up, burn everything, and plant it to soybeans. If I donít do it, someone else will probably be planting beans out there before spring is over with."

"How much do you need?"

"Arlene and I have been over it backwards and forwards," I told him. "We can handle buying the land since we can pay for it with soybeans if we have to. But to clean the place up and get it running again, we just donít have that kind of cash reserves. Weíre just guessing, but weíre going to need between another five and seven thousand to fix it up and get going again. We figure that after the first year we should be able to hold our own and gain a little on it."

"Would ten do you, then?" he asked.

"Probably close enough to get by," I told him. "Frank, Iím not looking for a handout, Iím looking for a loan that might be a while getting paid back."

"It sounds like youíve cut yourself a tough one," he said. "Having a loan like that hanging over your head can affect your mind, and it can be enough to be the difference between success and failure. Have they still got that board fence around the place?"

"Some of it," I said. "The rest is falling down. Weíre probably going to tear most of it down so we can have runoff areas in the corners, anyway."

"Leave some of it," he said. "Paint ĎFrank Blixter Ford, Livonia, Michiganí on it and send me a picture. That way I can write part of it off to advertising. You think that would be worth, oh, two thousand a year for five years?"

"Iíll do it if you want me to," I said. "I doubt like hell youíre going to draw much business to Livonia from Bradford, though."

"Well, youíre probably right about that," he smiled. "Although Iíve sold one car down there that I know of, so I can justify it as advertising, and maybe a little tax write-off thrown in there. Donít get me wrong, Mel. Youíre a friend, and you did an awful lot for me over the years, just sticking with me like glue through the hard times, so you deserve some of it back. But you want to know the real reason why Iím willing to do this?"

"Yeah," I said, scarcely able to believe my ears. An extra ten grand thrown into our plans was going to make a huge difference, especially if Arlene and I didnít have to pay it back.

"We raced an awful lot of places over the years," Frank said. "The majority of the races we ran were on existing tracks, although we can all remember racing in rodeo rings and on baseball diamonds. But you know what? A lot of those real tracks where we ran are gone, disappeared, planted to soybeans as you put it. I happen to think that not only is racing fun, itís important for a number of reasons, and weíre losing a lot of it. Now you come along, and the two of you are racers as through and through as anyone Iíve ever known, even if you havenít been behind the wheel of a race car for years. I wouldnít be surprised if you can make a go of it with a couple breaks. This is one of them."

What do you say to that? I mean, you can say "Thank you" all you want, but it still doesnít get the message across. Ten thousand dollars in those days was a hell of a lot of money. I wasnít making that much in a year as a teacher, even after nearly fifteen years on the job. That much was three cars, say, or a pretty decent house, or a good piece of a farm. It probably wouldnít come to a hundred thousand in todayís figures, but it would go a long way toward that figure. "I appreciate it, Frank," I told him. "Thereís no way to tell you how much I appreciate it. If this flops, Arlene and I will see that you get your money back. It may take us a while."

"Well," he grinned. "I wouldnít be doing this if I thought that you were in it to lose money. Youíre in it for the racing, for the sake of keeping racing alive. I think the two of you have just about everything you need to make a go of it. Frankly, Mel, I donít know of anyone else I would be willing to make this offer to, but the two of you have always had your heads screwed on tighter than anyone else I know."

"Iíll warn you right now, itís going to be a little slim and make-do the first year," I told him. "But we all know what slim and make-do looks like, so I donít have to fool you. Drop down on race day sometime this summer and you can see how well weíre doing."

Even though our business was taken care of Ė Frank wrote out a check on the spot Ė we went over the whole ins and outs of our ideas with him. He had a few ideas for us, and I was grateful to hear them Ė after all, heíd known more about promoting a race and bringing crowds in than I ever would. It was good to hear the criticism and constructive comments from the hand of someone who knew what Arlene and I were talking about. When you got right down to it, there couldnít have been a better person to bounce all those ideas off of, so it was good to learn from the hand of a master.

The early years of anything can be a struggle, but theyíre often the most exciting years. I caught the tail end of the early years of the MMSA, when it was an idea that had to claw its way up on its own merit. After an organization or an idea or whatever gets mature, some of that excitement of attempting something fades, and Iíd seen that in the last couple years of the MMSA as well. Now, we had the excitement and the interest of building something new from scratch, and I think it excited Frank as much as it did Arlene and me. "Let me know if I can be of any help with anything," is how he put it. "And Iím not just talking writing my name in a checkbook. Itíll be fun to do something constructive on something new."

"Iíll just take you up on that," I smiled. "The only way we can bring this off is to do as much as we can either by ourselves or by volunteer help, but if it works out I think itíll be good all around."

We didnít get out of there and on our way back to Bradford until after dark. Vivian served a fine dinner, while being part of much of the conversation, but eventually we had to be pointing it toward home or we were going to have Lauri wondering just what the heck had happened to us. We were out on I-94 before Arlene summed it up: "I figured weíd get the money, but I sure didnít expect to get it with so few strings attached."

"Me, either," I said. "It ought to be enough to make the difference between making it or not. Weíre just going to have to make sure every damn dime is well spent."