|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

|

Wes Boyd’s Spearfish Lake Tales Contemporary Mainstream Books and Serials Online |

Telzey was in a considerably different mood on Saturday morning, and for a number of different reasons.

Probably the most important reason was that there had been both e-mails and phone calls from both her parents. Her mother was still in Kuwait and was likely to stay there for the foreseeable future. Her father was still in Qatar, but expected to be moved to Kuwait in the next few days. Although both Telzey’s parents were in the same unit they had different specialties and worked in different sections, so it was hard to say if the two of them would be together, and, if so, for how long.

It was a tremendous relief. Although the war was still on and there was no telling how it would come out, things seemed to be going well at the moment.

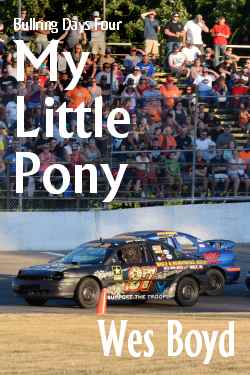

Telzey and Will had gone out back one more evening, this time to the track, where they raced each other with the kart and the ATV, switching off vehicles every now and then. Will showed her a few more tricks and she got to feeling more comfortable. The weather turned cold and rainy for a couple days after that, so they spent their after school time at Will’s house, playing a racing video game and watching a DVD that had been made of some of the races at Bradford Speedway the previous year. From what Telzey could tell from the video, the Pony Stocks were a little slower than the other classes like the Street Stocks and Sportsmen, but not all that much slower. Will confirmed it, telling her that the fastest Pony Stocks lapped quicker than the some of the Street Stocks, mostly because they tended to corner better since they were lighter.

The result was that Telzey had spent the last part of the week looking forward to going out to the shop and helping Will with his race car. She still paid attention to what was going on in the Middle East, but at least it wasn’t a full-time worry.

Instead of her usual Saturday routine of sleeping late and getting up groggy, Telzey was up early and ready to go almost as soon as her feet hit the floor. She got dressed, told her grandparents goodbye, and headed next door. Once outside, she realized that after the cruddy weather the last couple days, there now was a clear blue sky and frost all over everywhere. It looked like it was going to be a nice day for March once the sun had the chance to warm things up.

Will was still getting his act together, but his father was pretty much ready to go, sitting at the kitchen table with a cup of coffee in front of him. When he asked if Telzey had breakfast yet, she told him that she’d had a bowl of cereal and that was about all she ever had. “I don’t suppose you drink coffee, do you?” he grinned.

“I sure do,” she told him.

Almost immediately she had a cup of coffee in front of her. “That’s a little strange,” he commented. “Most kids don’t seem to care much for coffee. Will doesn’t like it, and Chuck only has a cup every now and then. I never got into it much until I was in the Army.”

“Maybe the fact that I grew up around the Army has something to do with it,” she told him. “I don’t remember ever not drinking coffee. I didn’t know you’d been in the Army.”

“I spent a couple years studying auto mechanics at a community college,” he told Telzey. “I was sick and tired of sitting in classrooms and decided I wanted the break. I figured that I could use the GI Bill money for college since I figured on being a teacher like my dad. I already liked working on cars so I joined to be a mechanic. Being in the Army was all right, but nothing that I wanted to do for a career, so when my time was up I got out and worked for a NASCAR Busch team for a while, then came back here. Then Dad and I decided to build the shop out at the track.”

Telzey shook her head. “I don’t know if I’m going to take after my folks and make a career out of the Army,” she told him. “But I think if I do I’ll want it to be as a mechanic, rather than in communications.”

“Have you ever worked on cars very much?”

“Not as much as I’d like to,” she admitted. “Just with my dad some, at home or at the auto hobby shop on base.”

“Well, it’s good to see that you want to get your hands dirty,” he smiled. “Ashley, the girlfriend Chuck has now, looks at an auto part about like it was a snake. I think it’s good that you want to learn something about cars, even if you don’t become a mechanic.”

“I think my dad would agree with you,” she replied thoughtfully. “He says that women usually don’t know enough about cars.”

“Boy, is your dad ever right about that,” he laughed. “And too often anymore boys don’t know that much about them either. When I was a kid it was part of growing up. Kids seem to know more about the guts of a computer these days than they do about cars. That isn’t all that bad, I guess, since computers are becoming more and more a part of cars. But what I wanted to explain to you was the deal I have with Chuck and Will. If they want to race they have to do their own work on their cars. I won’t do it for them. I’ll help if they need to know how to do something or need an extra pair of hands or whatever, but the work is theirs to do. You’ll mostly be helping Will. Probably today it won’t be anything that’s very complicated, just time consuming. If it gets too boring, let me know and I’ll run you home.”

“I don’t think it will,” she smiled. “What are you going to be doing?”

“I’m going to be working on my own race car today, and I’m hoping that Chuck will show up and work on his some, too. That is, if his girlfriend will let him.”

A few minutes later, the three of them were sitting in the front of Ray’s pickup truck as they drove under the overpass at the edge of town and past the huge General Hardware Retailers distribution center. “When I was a little kid, the track was right over there,” he told Telzey, pointing at the west end of the plant. “It was a quarter-mile dirt track, mostly flat in the corners. It was pretty run down when Dad bought it for a song. He was trying to fix it up, but didn’t have much money to work with. Then General came in and wanted the land and somehow he managed to get more money for it than he ever dreamed possible. So he decided to build the new track in the back of the farm he owned.” He shook his head and continued, “It’s hard to believe that was over thirty years ago, for Pete’s sakes.”

The shop proved to be a large, modern metal building with neat grounds. There were a handful of cars sitting outside, and a solid metal fence in back gave the promise of more cars sitting there. In the distance beyond, well off the road, Telzey could see a grandstand and light poles sticking up above an earthen embankment. “Wow,” she said. “All the times I’ve come to Bradford, I never knew this was here.”

“I suppose you’d like to look at the track,” Ray grinned, turning into the shop’s parking lot but driving past it on a narrow paved road. Not far past the shop he came to a stop at a gate in a woven wire fence that surrounded the track. Without his father saying anything, Will got out the right side of the truck, went up to the gate, unlocked and opened it, then came back and got in the truck. Ray drove on, up a slight grade and past a couple buildings that looked like smaller versions of the shop, and then past a small grandstand to an opening in the wall, where he stopped.

Telzey looked around. In a way, it looked like a half-sized version of the speedway at Martinsville. It was small and compact; the turns were steeply banked, and the front straight had some banking to it as well. The infield was almost fully paved, protected by a concrete wall; another concrete wall surrounded the outside of the track, and there was a high catch fence most of the way around the track as well. On the far side of the track from them sat a large grandstand, extending the length of the straightaway and into the turns a little. At the top of the grandstand was a scoring stand; a flag stand overlooked the painted start-finish line.

“The area in back of us we use as overflow pits when we have a big show,” Ray explained. “Most weeks, there’s room enough in the infield for everyone to pit. The concession area is on the far side of the grandstand, although there’s a small concession stand in the pits, as well. You like to take a ride around the track?”

“Sure thing,” Telzey replied, barely able to contain her excitement.

“Figured you’d say that,” Ray laughed, and headed the truck out onto the track.

He really didn’t go all that fast, maybe highway speed, but it felt pretty fast. It was fast enough in the corners that Telzey could feel herself being pushed sideways up against Will. It didn’t take much for her to imagine herself being behind the wheel, going faster, with the track lights on and a crowd in the grandstand. That would be so neat! And who knew, it might really happen . . .

“The two corners are pretty close to being the same,” Ray explained as he headed around for a second lap. “For some reason no one has ever been able to explain, the ideal groove for three and four is about half a lane higher than it is for one and two, so you have to wind up driving both corners different, especially if you’re passing. Generally speaking, the ideal groove to pass in one or two is on the high side, and low in three or four. There’s really not that much difference though, and the track is wide enough to go three wide, four wide on the straights if you’re careful. It’s when everybody tries to go four wide in the first turn after the green flag that everything gets interesting.”

“And when the wrecker gets involved,” Will snorted. “I went from eighth to second in the first lap of one heat last year and didn’t pass a car.”

“There are times when standing on the gas and turning left isn’t always the way to win a race,” Ray agreed. “That was one of those times and Will played it smart. I always tell people not to try to win the race in the first corner, but they don’t always listen to me. It often gets wild in the Pony Stocks because there’s always a bunch of novices who don’t always know when to be cool.”

“But it happens with everybody else, too,” Will added with a grin.

After a couple laps, Ray pulled off of the track at the turnout on the back stretch. “That’s enough for now,” he told Telzey. “Believe me, if you’re involved with us out here you’ll get to know every inch of the place. But now, we’ve got other work to do.”

Ray drove the truck back down toward the shop, pausing at the gate to have Will close and lock it. He parked outside of the shop and they got out of the truck and went inside a back door.

Even without the lights on there was a lot of light coming in the windows, and it was almost bright in there when Ray turned on the overhead lights. The shop was neat and clean, although clearly an auto shop; there were various machines sitting around, and various work bays where there was one or more bright red tool chests. “I don’t like a messy shop,” Ray said as Telzey looked around. “It’s important to clean up after yourself or it turns into a junk heap almost instantly. What do you say we get out some race cars?”

It turned out that one end of the building was unheated, and accessed through a large overhead door. Inside were a number of cars that mostly looked like race cars; some were covered with tarps. One of those nearest the door looked almost like a mockery of a stock car – it was much lower and covered with thin, square-cut metal. It was white, with a dark blue “59” on the side, many decals and stickers, and it proved to be Ray’s Modified. “I’ve got some piddly stuff to do to it,” Ray explained as the three of them pushed the car out into the main shop, “so I might as well get it done before we get into the season.”

They went back into the cold part of the building to a beat-up looking blue car with a white “89” on the side, again with a number of decals and stickers, and like the modified, “Austin Auto Service” lettered on the side. “This is my car,” Will explained. “It doesn’t look like much, but we’re going to clean it up and paint it before the season gets started.”

Telzey took a close look at the car. It was a small, four-cylinder economy car that looked sort of familiar, but it looked like a race car, too. All the glass had been removed from the windows, and the interior was gone as well. There was a heavy-duty roll cage built inside, looking very solid. There were braces on the right side in such a way that a passenger couldn’t sit in it. The regular seat had been replaced with a hard-looking metal seat bolted directly to the roll cage. The dashboard was gone – there were some instruments fastened in front of the driver, and some switches mounted to a panel mounted on one of the members of the roll cage, with a number of wires connected up through the firewall. Even the steering wheel was different; it was removable, to aid getting in and out. Will had to put the steering wheel on the column to be able to steer it as they pushed it into the main shop.

“So what are we doing to this today?” Telzey asked.

“We’re going to try to get it looking a little better,” Will told her. “It was blowing smoke toward the end of the season, so we rebuilt the engine. Now, it just looks bad, and that doesn’t look good for the track. I’ve got a new fender for it, and we’ll get that on today. Then there are some dents that we’ll roll out, and we need to take off all the decals and stuff so we can repaint it. I want to do the inside, too, so that means we’ll have to yank the seat and some other stuff from the inside and mask some stuff off.”

“It looks like a lot of work,” Telzey said. “Are we going to get it all done today?”

“Most of it, I hope,” Will told her. “It should go pretty easy, since we’re really not looking for body-shop quality. I’m hoping we can get the paint on next weekend and put everything together the weekend after that. We may have to work on it after school some to get everything done before the season opens.”

“Yeah, we let things slide a little,” Ray admitted. “We probably should have been doing this a month ago, but, well, stuff happened.”

“Why don’t you get started peeling off the stickers and stuff?” Will suggested. “I’ll get you a razor blade and a holder. Most of the stuff should peel up fairly easily, but try not to gouge the paint too much. The stuff you peel up is just trash, throw it away. I’ll probably call for you to help me from time to time.”

They got to work. Taking off the decals wasn’t quite as easy as Will made it out to be, but Telzey made good progress on it while Will went to work with wrenches removing a battered left front fender. He just about had it off when Telzey heard a strange voice: “Glad to see that someone thought to make coffee this morning.”

She looked up to see an older man with short gray hair not far away. “Oh, hi, Dad,” she heard Ray say. “So what’s happening this morning?”

“’Bout the same,” the older man chuckled. “I see we got somebody new today, and somebody that’s a lot prettier than you two.”

Telzey didn’t feel very pretty at the moment, what with paint chips and parts of decals stuck to her clothes, but she smiled at the compliment. “Yeah, Dad,” Ray spoke up. “This is Telzey Amberdon, Will’s new friend from next door. Telzey, this is my father, Mel.”

Telzey was looking up at him from her seat on the floor, where she’d been peeling stickers. From talking to Will and Ray she knew he had to be pushing eighty, but he didn’t look that old. He was a tallish man, a little on the solid side, and a nice chuckle on the face. “Pleased to meet you, Mr. Austin.”

“With three Mr. Austins around here maybe you’d just better call me ‘Mel,’” he smiled. “Everyone else does, and it’s less confusing that way.”

“I guess, if you say so,” Telzey replied, a little shyly. There was something about him that seemed like a teacher – and with good reason, for she’d been told that he had been one for many years.

She seemed at a loss for anything else to say, but Ray saved her by asking, “So what do you have on your list today, Dad?”

“Thought I’d drag the sweeper in and go through it, see if maybe I can get it to start a little easier.”

“Fine with me,” Ray said. “That’s another one of those things that really needs to get done before the season starts, and you’ve got a better touch with that old flathead engine than I do. If that sweeper was really worth anything I’d still be tempted to hang a new engine in it.”

“Not worth the bother if we can get another year or two out of it,” Mel replied. “Telzey, can I borrow you for a few minutes? I imagine you’re getting pretty bored with peeling decals.”

“It’s not that bad,” Telzey admitted, “and I’m almost done.”

“Telzey, I don’t know how much Ray and Will have taught you yet, but there’s one thing about race cars: you’re never done piddling with them,” Mel laughed. “There’s always something else to do.”

“I think I’m beginning to understand that,” she smiled at him.

“You might want to go get your coat,” he told her. “We’re going to have to go get the sweeper.”

Telzey got up from the floor, and picked her Jeff Gordon jacket up from the back of Will’s car. “Oh, another Jeff Gordon fan?” Mel smiled. “I have to say, you’ve got taste.”

“I just hope he gets to running better,” she said as she pulled it on.

“Probably he does, too,” Mel told her. “Any decent race car driver always wants to run better. If they’re satisfied with how they’re running, even if they’re winning, then they’re not racers.”

Telzey followed Mel outside to his car and got inside. “Ray tells me that your folks are both in the Persian Gulf,” he said as he fastened his seat belt.

“Both in Kuwait,” she replied, then added, “at least Dad should be there by now, he’s been in Qatar.”

“Not in combat units, then?”

“No, Signal Corps,” she said as he started the car and backed out of the parking space.

“You’re worried about them, I bet.”

“An awful lot,” she admitted.

“Telzey, I don’t know if it’ll help any, but I was on Okinawa back in World War II, and I can tell you that being near combat and being in combat are really different things. I was a mechanic there and I was just glad I wasn’t carrying a rifle.”

“I keep telling myself that,” she replied. “But then I see all that stuff on TV, and I can’t help but worry. Will has been helping me keep my mind off it, and that’s helped a lot.”

“I understand,” Mel told her. “It’s a lot different from how it used to be. Folks at home in World War II didn’t always have that many details about what went on. Live TV from the battlefield brings things a lot closer to home.”

It only took them a minute to get to the back gate to the race track, the one that they had gone through earlier. Mel stopped outside the gate and handed her a key. “Would you like to go unlock the gate? I think we can probably leave it open today while we’re here.”

It took a minute or so for Telzey to get the gate open, then she got back in the car. “Seat belt,” Mel reminded her gently. “We’re not going that far, but it’s always a good idea to wear one, and an even better idea to be in the habit of wearing one.”

“Yeah, I almost always wear one,” she said. “I should have thought of it.”

“Telzey,” Mel grinned, “the first race I ever ran, I won because I had an army web belt fastened around the seat and me. That was back in the day when no one had ever heard of such a thing, even in race cars. I’ve hardly ever driven a car without a seat belt since then, and I’ve always felt nervous without it. I’d really rather have a five-point harness than an air bag. They’ve saved my life more than once.”

“You’re a racer too?” she smiled.

“Not anymore,” he told her as they got moving again. “I raced professionally for years, back in the fifties. Arlene made me quit when we had kids, but I ran the odd race once in a while after they’d grown up a bit, just to see if I still could. Mostly I was involved in helping run the track, first the old one where the General plant now sits, and then here.”

Telzey suspected that Mel had a lot of stories about the old days and suspected that she’d enjoy hearing some of them. It wasn’t long before they pulled up at one of the small steel buildings on the back side of the track. “You ever drive a tractor, Telzey?” he asked.

“No,” she said. “The only thing I’ve ever driven is Will’s ATV and his kart.”

“Not even a car?” Mel frowned.

“Dad said we ought to go out on the back roads in the training area some time so I could get a feel for it, but we never got to do it before he had to go to the Gulf.”

“Cripe, I should have asked first,” Mel smiled. “I guess I’d better give you a driving lesson.”

“Sure, I guess it’d be all right.”

“Telzey, if you’re worried about it, I’ve taught Driver’s Ed for over forty years. In fact, it’s coming up on fifty, because I still do it some to fill in. Most of the people that have graduated from Bradford High School learned how to drive from me, or at least had some lessons from me. That includes your mother, and I remember she was not the easiest pupil I ever had.”

“When Mom and Dad are going somewhere together she usually lets him drive,” Telzey observed.

“Some people just aren’t comfortable with it,” he grinned. “However, from what Ray and Will tell me about how you handle that kart and that ATV, I don’t think you’re going to be one of them. Let’s switch sides and I’ll give you a run-through.”

The next hour was spent with Mel sitting on the right side of the car, coaching Telzey through the basics of driving a car. It was a lot different from driving the ATV or the kart, mostly because the car was a lot bigger and heavier. They just drove around the network of paved roads and the parking lot at the track, although toward the end of the lesson Mel pointed her out onto the track proper. “You’re probably chomping at the bit to try this,” he smiled. “Keep it under forty this time, just to get used to it, but you’re doing so well I might just have to come out here with you another time and let you try hot lapping it a little.”

“Really?” she said in surprise.

“Actually, most of the kids I’ve taught to drive since the late sixties have had the chance to drive on the track a little, just to see what it’s like. Some of them went on to be racers. I kind of have the feeling that you’re going to be one of them.”

At forty miles an hour, driving around the track was just driving, although she could feel the car having to work in the corners a little. She found herself crowding it just a little, playing with the car in the corners to get a feel for how it handled. Even more than earlier she could imagine herself sitting in a car like Will’s, hot lapping the place when the lights were on and the grandstands were filled with fans.

“That’s enough for now,” Mel told her. “We’ll do it again sometime. Head it back up to that building we were at earlier.” Once they got there, Mel told her that he’d drive the tractor back down to the shop, and she could follow him in the car.

Even though they weren’t going very fast, it was thrilling for Telzey to be driving Mel’s car by herself as she followed him down to the shop. It was something that no one her age that she knew except for Will had done, at least that she knew of. It made her feel very grown up and she was especially thrilled that Mel would allow her the responsibility. She couldn’t help but wonder if maybe she’d have the chance to drive Will’s race car before the summer was over with, at least just around the track, if not in a race. And, as far as that went, she knew that Kayla was expecting to take Driver’s Education that summer. At her age, it would be next year for sure. She realized it would depend on where she was living then. She really hoped it wouldn’t be in Bradford, that her folks would be back from the Gulf and they’d be together again.

Feeling a lot more grown up than she had a couple hours before, she got out of the car and followed Mel into the shop before he closed the overhead door. “Thank you,” she told him. “I really enjoyed that.”

“You acted like you did,” he grinned. “What do you say we go find out if that coffee is still good?”

They headed into the office, where there was a coffeepot sitting half full. “Probably should be all right,” Mel said. “Ray told me you’re a coffee drinker.”

“Yes, I am,” she replied shyly.

Mel filled a Styrofoam cup for her. “We run the shop out of here,” he explained. “It’s pretty much Ginger’s country, she does the books and keeps up with a lot of the track stuff from here, so for practical purposes it’s the track office except on race nights. Did Ray tell you about how all this happened?”

“A little bit,” she told him. “Just how you used to have a little dirt track down where General is now.”

“Guess he didn’t get into it too much,” Mel said as he poured a cup for himself. “Are you up for the full story? Ray and Will have heard it so much that they’ll be bored to tears if we go out in the shop and I tell you.”

“I really should be helping Will with his car,” she replied. “But I’m curious about all this, too.”

“Tell you what, let’s just sit here and finish our coffee and see how far I get. Then we’ll head back out into the shop, and if we bore them we bore them.”

“It’s all right with me,” she smiled, heading over to the coffeepot to top up her cup as Mel sat down on a desk.

“I told you that I was on Okinawa,” Mel began. “Well, while I was there, I met a guy by the name of Frank Blixter. He was, oh, in his thirties at the time and he’d been a racer before the war, midgets and what we used to call big cars, but would call sprints today. Well, after the war we went our separate ways, but along in the spring of 1950 I ran into him again. He and Spud McElroy, another guy I knew on Okinawa, had gotten together and had set up this little traveling series of special midget cars called the Midwest Midget Sportsman Association. Since Frank and Spud owned all the cars they could keep them competitive with each other. Anyway, they were short a driver, and they asked if I’d like to drive for them for one night. I wound up driving for them for most of five years and won the MMSA championship three times. We traveled all over the Midwest from the Rockies to the Appalachians, and down south in the spring and fall. Sometimes we’d race six and seven days a week, almost never in the same place two days running.”

“That’s a lot of racing,” Telzey commented.

“Darn right,” Mel nodded. “The guys that just race here usually race about twenty nights a year. We were doing as many as two hundred, so I packed a pretty good career into those six years. The last part of it Arlene, that’s my wife, Ray’s mother, was racing a car there, too. She was pretty good and I still think Frank and Spud cut her a little slack in the engine department for the sake of promotion, but they’re both dead now so I’ll never know. Well, anyway, by 1954 both Arlene and I were getting a little tired of that kind of life and we’d been getting a little sweet on each other. Then, along in early July, we were running a one-night stand at the old dirt track here in Bradford when another car busted a tie rod end and I hit it up pretty bad, and got banged up pretty bad, too. I didn’t come to for several days, and discovered that the show had moved on but that Arlene had stayed behind to be with me. She didn’t want to leave me stranded and alone in the middle of nowhere. They needed nurses at the hospital and she was a nurse, so that made it a little easier to stay. Well, I was starting to get around on crutches when one of the other nurses found out that I was a certified high school teacher. There was a teacher shortage at the time, and I had the school superintendent down there just about that quick offering me a job as the auto shop teacher. Well, Arlene and I talked it over and we decided that we could do a lot worse, so I took him up on it and we got married.”

“There’s a romance for you,” Telzey smiled.

“Oh, yeah, it was different, and that was back in the fifties, when things were a lot different, anyway, but that’s neither here nor there. Well, anyway, I still had some racing in my blood, but Arlene and I figured that we’d better not get too serious about it. So we got to working with Smoky Kern, the guy that owned the short track here, just helping put on the races and keeping things organized, helping new people learn about race driving, and like that. There’s no point in going into the ins and outs of it, but Smoky wasn’t the best businessman and he had a temper and got people mad at him at times, even finally got me mad enough with him to tell him goodbye.

“Back in those days I mostly read the Chicago Tribune, but one day I happened to open a Detroit Free Press and saw an ad for Frank Blixter Ford in Livonia, which is right outside Detroit. I’d lost track of Frank years before, but it was summer and I wasn’t doing anything, so the next day I drove up to Livonia, and sure enough, it was the Frank I knew.” He finished his coffee, threw the cup in the trash, and said, “Come on with me, I got something I want to show you.”

They headed out into the shop, to find Will and Ray working on taking things out of Will’s car. They walked outside and got in Mel’s car as he continued. “Anyway, it was good to see Frank again, and we didn’t have any hard feelings or anything about the way things had ended. Frank told me years later that at the end of that last season I was with them and decided that things weren’t going all that well anymore. They’d had a pretty good offer to sell the whole outfit to a guy that thought he could do better, and they took him up on it. Frank said that the guy didn’t want all the junk parts and stuff he’d accumulated over the years, which included some busted up race cars. Well, I asked him if he still had any of that stuff and he said he had it all stuck in a barn somewhere, and he thought there was stuff enough to build a car or two out of it. By then, he’d heard that all the other cars had been scrapped after the new guy went bust.

“Well, Frank and I talked it over a bit, and I told him I was sort of looking for a project car for my advanced auto shop kids,” Mel continued as he braked the car to a stop in front of a metal building near the grandstands. “He said I was welcome to all that old junk, so long as we’d paint ‘Frank Blixter Ford’ on any of the cars we restored.” Mel led Telzey into the building, where there was a long row of old race cars, some covered with tarps. They went over to one of the cars covered with a tarp, and together they started to peel it back. Sure enough, there was an old-fashioned midget, in perfect shape, even with a nice coat of wax. It was red and white and had the number “2” painted on it, along with “Frank Blixter Ford.”

“This is the first of the two cars that my auto shop kids and I did out of that old pile of junk. It actually was Arlene’s car; it had gotten banged up pretty bad after we left the show. It’s pretty close to all original parts. The other one, the 66 car, was painted for my old one, although it’s about half a replica and I don’t know if any of the parts actually came from the old 66.”

“Wow, this is really neat!” Telzey said. “Could you still race them?”

“In theory you could,” Mel grinned. “In practice, the only time they’ve been raced was when we opened the new track, Arlene and I ran a little exhibition to dedicate the place. She won, by the way. There are classic car races, but I just don’t want to risk them. These two cars are our good luck charms, we always open the season with a ceremonial parade lap with them. These are pretty old cars, the design is right straight out of the 1930s, rail frame, Ford V8-60 engines, and they wouldn’t be considered safe to really race anymore, with no roll cage and only a lap belt. But these are the only two surviving MMSA midgets in existence. The MMSA midgets were always considered a little weird, since they had a clutch, a transmission, and a self-starter, and usually you don’t see those on midgets.”

They took a few minutes to look at some of the other cars. One was an old-fashioned upright front-engine Indy car, and next to it a somewhat newer rear-engine Indy car, which Mel told her was the last Offenhauser-powered car to attempt to qualify for the 500.

It took them a while to get back to the main shop. “I’ll bet he took you back and showed you the midgets,” Ray laughed when he saw them.

“Well, one of them,” she grinned. “Those are really neat. Those old Indy cars are cool, too!”

“Yep, she’s hooked,” Ray laughed again. “Not that I expected any different.”